Two Tales: Goodyear and Parr

![]()

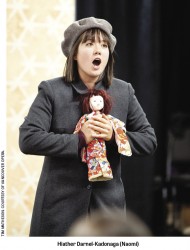

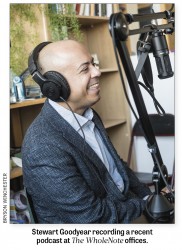

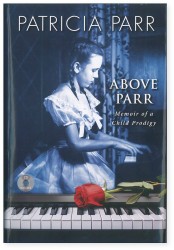

Parallels can be an interesting way of laying down the tramlines of a story, as long as one doesn’t try to force them to intersect! Around the time I was planning to get together for what seems to be becoming an annual (podcast) chat with concert-pianist Stewart Goodyear, I received in the mail, courtesy Prism Publishers, a just-published memoir titled Above Parr: Memoir of a Child Prodigy by pianist Patricia Parr, due to be launched on December 1 at Hazelton Place in Toronto (the same day this issue of our magazine hits the streets).

Parallels can be an interesting way of laying down the tramlines of a story, as long as one doesn’t try to force them to intersect! Around the time I was planning to get together for what seems to be becoming an annual (podcast) chat with concert-pianist Stewart Goodyear, I received in the mail, courtesy Prism Publishers, a just-published memoir titled Above Parr: Memoir of a Child Prodigy by pianist Patricia Parr, due to be launched on December 1 at Hazelton Place in Toronto (the same day this issue of our magazine hits the streets).

Growing up in Toronto features prominently in Patricia Parr’s story, as it does in Stewart Goodyear’s. So too does the challenge of what one might call “the downside of the upside” – namely how the individual artist deals with being labelled a child prodigy very early on, in a culture that takes nearly as much delight in falling stars as it does in rocket-like rises to fame.

Patricia Parr’s rise was particularly meteoric. She had played her first solo concert at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto in 1944, at the age of seven, attracting plaudits from the music critics of all three Toronto papers.

Patricia Parr’s rise was particularly meteoric. She had played her first solo concert at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto in 1944, at the age of seven, attracting plaudits from the music critics of all three Toronto papers.

“‘Genius,’ ‘wonder child,’ ‘prodigy.’ On it went: a litany of accolades,” she writes. “From the age of eight onwards, I was performing as soloist with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in Massey Hall; the Toronto Philharmonic at the ‘Prom Concerts’ in Varsity Arena; the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in the Eastman Theatre, and the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall. I held the distinction of being the youngest artist ever to be engaged with these orchestras – although for the life of me I don’t know how, or why, any of this materialized.”

By 14, Parr had been taken on as a piano student by Isabelle Vengerova in New York, planning to fly back and forth to New York for monthly lessons. But Vengerova was having none of it, and by the age of 15 Parr was living with an aunt and uncle in a suburb of Philadelphia, on full scholarship at Philadelphia’s famed Curtis Institute, “the equivalent of attending Harvard to study law,” as Parr puts it. Vengerova had taught at Curtis from its inception in 1924, whipping into pianistic shape “the likes of Gary Graffman, Leonard Bernstein, Jacob Lateiner, and Lucas Foss.”

Parr’s life journey after the Curtis years is the story of a gradual, and in parts very painful, journey away from the solo piano careers that Curtis (and perhaps most conservatories and the students that attend them) sees as the highest form of their art. It’s fascinating, though, to see how the earliest steps on what was to become her primary musical path can still be traced back to those formative Curtis days.

“In the mind of my mother,” she writes, “you needed to be a soloist to be considered successful. However there are many fine musicians who simply do not thrive under the solo limelight and choose other ways of revealing their talents…[establishing] themselves first as chamber musicians, and then [moving] on to their particular field, whether as a soloist, a teacher, or a recording artist… The experience of sharing musical goals, the rapport you establish with your colleagues, and the insights you receive from playing with them have always elevated my artistry, filling me with the greatest satisfaction…”

As her memoir reveals, that satisfaction reached its peak in her work, for 20 years starting in 1988, as a founding member of the Amici ensemble in partnership with clarinetist Joaquin Valdepeñas and cellist David Hetherington – an ensemble which by its instrumental make-up dictated from the start that they would have to invite “amici” into every concert they performed. Whether she found this niche thanks to the Curtis years or in spite of the Curtis years, readers of Above Parr will have to decide for themselves.

Stewart Goodyear’s arc as a performing artist is still very much on the ascendant – who can say how far he will continue to rise? – so it makes sense that he has no particular reason to dwell on the kind of end-of-career self-reflection that Parr’s memoir engages in. So let’s just say for now that it is interesting, in terms of biographical parallels, that he, like Parr, found himself, at the age of 15 (albeit decades apart) also enrolled at Curtis, at the very moment when precocious talent sometimes starts to flower or else to wither on the vine.

Curtis, for Parr, had meant five years of study with Vengerova, her “Beloved Tyranna,” as well as, for a lesser time, with Rudolf Serkin, after Vengerova’s retirement. Goodyear’s equivalent mentor was Leon Fleisher. In our recent podcast interview, as in earlier conversations, Goodyear describes (with what seems, to the outsider, almost incomprehensible relish) the rigours of the pedagogical process he went through with Fleisher. Basically it entailed bringing to class performance-ready (i.e. committed to memory), in its entirety, one Beethoven sonata a week for 32 weeks – “Well, 33 weeks actually,” he says. “I had two weeks for the [close-to-50 minute] Hammerklavier.”

As important as laying down early in his career the physical and intellectual stamina to absorb, process and perform new repertoire at a punishing rate, the exercise also gave permission, in Goodyear’s approach to his art, for something that seems to have been a key part of his musical makeup from his earliest days: the desire and ability to see individual pieces within the larger stories they are part of. In our recent podcast conversation he cites, as an early example of this, listening to The Beatles’ White Album. Even though it was multiple tracks on two records, he explains, for him it was one album, a single story.

One can see this fascination with narrative and emotional through-lines brought to giddying heights in his grand projects, such as his Beethoven “Sonatathon” which entails playing all 32 sonatas, in order of composition, in three sessions over the course of a single day. Or, as he did recently with the Niagara Symphony Orchestra two days in a row, playing all five Beethoven piano concerti in a single concert. Discussing the Niagara concert, I challenged his commitment to chronological order, pointing out that he had played No.2 before No.1. He was quick to set me straight, pointing out that No.2 was in fact composed before No.1 was.

It’s as though he commits the the pieces he performs to logical and emotional memory, by accessing the emotional and historical narrative of a given composer’s life as it reveals itself, moment by moment in the works that give expression to that life. Goodyear will freely admit that his approach to the music he plays is very emotional, and he’s never shy of letting loose dynamically to express it. “I don’t mind making an ugly sound,” I remember him saying, “but it has to be what the composer was feeling.”

Autobiography: It is also possible to see how he applies that same storytelling rigour to the mixed programs he puts together for recitals. Take his upcoming concert December 4 at Koerner Hall. There are telltale fingerprints of his musical relationship, past and present, with Toronto, his home town, all over the program.

It starts with the first piece on the program, Bach’s Partita No.5 in G Major BWV 829 which was, as Goodyear explains, on the very first recital that Glenn Gould gave, in 1955, at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. That particular Gould recital captured Goodyear’s imagination to such an extent, that he reconstructed the same program last year at the Phillips Collection, in celebration of the 60th anniversary of Gould’s original landmark recital (and will repeat it again later this spring on February 5 for the Women’s Musical Club of Montreal).

The program continues with Beethoven’s Sonata No.32 in C Minor Op. 111, one of the first three that the 15-year-old Goodyear had to learn for Fleisher at Curtis, and the triumphant finale of his first one-day Beethoven Sonatathon as part of Luminato, at Koerner Hall, in 2012. The program then continues with a work of his own, Acabris! Acabras! Acabram! a world premiere based on a rather diabolical French Canadian fable and commissioned from Goodyear by Phil and Eli Taylor (name sponsors of the young artist program at the RCM) in celebration of the sesquicentennial.

Two diabolically difficult pieces by Fryderyk Chopin follow (Fantaisie-Impromptu in C-sharp Minor Op. 66 and the Ballade No. 4 in F Minor Op. 52) after which the program concludes with what he calls the “dessert after the main course” selections from his own concert-length arrangement of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker (which incidentally he will take to the Phillips Collection this year December 18, in a return visit “after his noteworthy re-creation of Glenn Gould’s iconic 1955 recital last season.”

On the road: Interesting as this one program is, the range (both geographical and in terms of repertoire) that he will cover over the course of the winter and spring tells the story of a solo artist, not content with a particular niche, continually bent on both discovery and rediscovery.

In addition to the performances already mentioned, he will do Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.2 in Memphis on January 14 and 15; Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No.1 with the Toronto Symphony Orchstra, in Ottawa, Montreal and Toronto (January 24, 25 and 27); and then a recital program at the Burlington Performing Arts Centre on February 3, 2017.

After that it’s Grieg’s Piano Concerto in Halifax February 9, Mussorgsky’s original solo piano version of Pictures at an Exhibition in Prague on February 15, Poulenc and Prokofiev in Omaha on March 17 and 18, and to top it off, a performance of the Beethoven Sonatathon on March 28 at the Savannah Music Festival, in Georgia.

“Goodyear’s commitment to classical music began at age three when he was introduced to Beethoven’s piano sonatas through recordings by Vladimir Ashkenazy, which he listened to in a single day,” the notes for the festival inform us…

Two Tales: Parr and Goodyear: parallels can be an interesting way of laying down the tramlines of a story, as long as one doesn’t force them to intersect. The world allows for many different iterations of a fulfilling musical life.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com