Total Immersion at Montreal Chamberfest

![]()

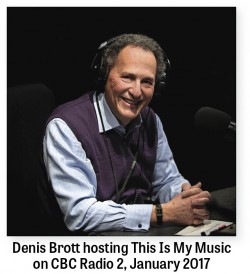

Denis Brott, founder and artistic director of the Montreal Chamber Festival (MCF/FCM), now in its 22nd year, and I are about 20 minutes into a lively phone conversation and I’m explaining to him why this year, more than any other so far, I have a hunger to play hookey from my work here and head east to take in all three weekends of MCF/FCM.

Denis Brott, founder and artistic director of the Montreal Chamber Festival (MCF/FCM), now in its 22nd year, and I are about 20 minutes into a lively phone conversation and I’m explaining to him why this year, more than any other so far, I have a hunger to play hookey from my work here and head east to take in all three weekends of MCF/FCM.

“I heard the complete Beethoven String Quartet cycle done by the Amadeus Quartet in Toronto over a two-week period in April 1976,” I explain. “Eight months after arriving in Canada. Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday, Monday, Wednesday, Friday, I think. It was…” I struggle for words.

“So you know what I am talking about then,” Brott jumps in. “It is really a life-altering experience and I am hopeful the public will appreciate it as such, and appreciate the wonderful playing of what I consider to be the foremost young quartet before the public today.”

He’s talking about the Dover String Quartet, winner of the 2013 Banff International String Quartet Competition, and the fact that the quartet will play the entire Beethoven cycle at MCF/FCM on three consecutive Fridays and Sundays starting May 26 and ending Sunday, June 11, 2017.

“How long has something like this been in the planning?” I ask.

“Years,” he replies. “Three, probably. I was in Banff the year they won, teaching. And I was asked to give a lecture on the final day of competition, right before the Beethoven round, on the subject of the emotional language of Beethoven. I had been there all week listening to all the rounds with avid interest and I had picked out right from the beginning the exceptional nature of the Dover Quartet, their emotional intelligence. They ended up being grand prize winners and winners in almost every area of the competition.”

He invited them to MCF/FCM right away, he says, and they’ve been there almost every year since. “This profession [chamber music] is one where people actually make friendships and colleagues and experience camaraderie,” he says. “It’s one of the things that makes chamber music different from almost every other segment in the music world.”

The idea of doing the cycle was one that he raised with them right from the start. “I planted in their ear right away that any quartet that takes itself seriously has to play the cycle – something I remember from when I jumped into the Orford Quartet in 1980. In one year I had to learn all the quartets and play the cycle. Believe me that was quite an undertaking.” It was during Brott’s eight years with the Orford that the quartet completed their landmark recordings of the Beethoven quartets for Delos over an 18-month period from 1984 to 1986.

The idea of doing the cycle was one that he raised with them right from the start. “I planted in their ear right away that any quartet that takes itself seriously has to play the cycle – something I remember from when I jumped into the Orford Quartet in 1980. In one year I had to learn all the quartets and play the cycle. Believe me that was quite an undertaking.” It was during Brott’s eight years with the Orford that the quartet completed their landmark recordings of the Beethoven quartets for Delos over an 18-month period from 1984 to 1986.

“So I encouraged the Dovers, and said when you have it up, let’s do it at the festival. And when it became clear that this would be the year, I said, okay so then we should do a festival theme of Beethoven; the whole idea of Beethoven’s role as a pivotal figure in the transition between the classical and Romantic era.”

Beethoven has fascinated Brott for decades, he says. “I have played every single piece he wrote that has a cello in it, and it’s a musical language that I understand and enjoy, and more than enjoy, that I am in awe of. I am privileged to have access to playing this music and obviously in designing this season I wanted to have a Beethoven work on every concert or most concerts where possible, and that’s what I have done. And I have put it together with a great deal of care over the last year and a half, two years; you know it takes about that long.”

The Dover Quartet, it should be said, will have completed two other complete Beethoven cycles this season, one in Buffalo, one in Connecticut. But each will have consisted of coming to town for two concerts, on three occasions spread out through the year.

“I come back to what I said before,” says Brott. “Experiencing the cycle in a condensed time frame, for audience and performers is quite remarkable. I remember doing it with the Orford at the Rubens House in Antwerp, the atelier of the artist Rubens, and there was a concert every second night with one night in between. So let’s say the Dover have been in training for doing this, and they are looking forward to it; needless to say we are looking forward to it immensely.”

Of the aforementioned other two Beethoven cycles on the Dover Quartet’s calendar this year, the Buffalo engagement is a highly idiosyncratic one: the “Slee Cycle,” which has been running since 1955, requires quartets to perform the cycle in the exact sequence preferred by Frederick Slee who endowed it.

“Did you have discussion with the Dovers about the sequence for your festival?” I ask. His reply is emphatic. “You are asking a fundamental question about what I believe in as a director, instigator, shepherd, call it what you like. The way you have people perform at their best is by letting them do what they want, as artists, people of distinction. On something like this I would never impose my will. They are presenting, it is in my interest for them to be playing at their best.”

Listening to Brott talk about the rest of the programming for the festival (and the Beethoven cycle is only the main course of a very satisfying full-course musical meal), the same sense of enjoyment at empowering inclusion comes through again and again. All built around the camaraderie he referred to earlier in describing chamber music’s unique place in the musical world.

“So how many people do you think will come for the whole cycle?” I ask, wistfully returning to the idea of making a two-week and two-day pilgrimage, for my older self to revisit one of the formative experiences of my musical life.

“How many people will take in the whole cycle? I don’t know. But it is a festival in every sense; an immersion, a celebration, so you have to be into immersion, not just social concertgoing. It’s for people who are as passionate about the music as the musicians. Just think of it this way. Two or three weekends in a row in Montreal is not so bad!”

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com