A Lecture on the Weather

![]()

It’s November at last, in a more than usually acerbic election year in the USA, in the final days of a presidential campaign revolving in large part around a slogan about making America great again. All of which causes me to recall a moment in CBC Radio history, just over 40 years ago, that not only continues to hold its significance, but takes on a new resonance.

It’s November at last, in a more than usually acerbic election year in the USA, in the final days of a presidential campaign revolving in large part around a slogan about making America great again. All of which causes me to recall a moment in CBC Radio history, just over 40 years ago, that not only continues to hold its significance, but takes on a new resonance.

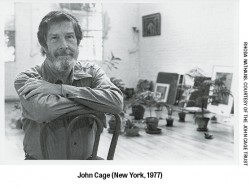

On the eve of the US Bicentennial year in 1976, CBC Radio Music commissioned American composer John Cage (1912-1992) to create a work to serve as a part of CBC’s observance of those 200 years of American history. Richard Coulter, my colleague in the national music department of CBC Radio, had already begun looking, in 1975, for a major American composer who might accept a CBC Radio commission through which to pay a musical tribute to the upcoming event. Richard knew Aaron Copland, having worked with him in Stratford, but when asked, Copland said he was overwhelmed with work and was too busy to even consider the project. Richard turned to me “as a former Wisconsinite” to discuss where to look next. We both concluded that Cage would be a most suitable alternative. Richard had, in previous years worked on the Music of Today series with Norma Beecroft and Harry Somers, and several of those programs had dealt with John Cage. And, as Richard recalls, Cage “had made a couple of earlier visits to Toronto including his obsessive chess game at Ryerson with Marcel Duchamp in 1968. So I was acquainted with his processes through the years.” So we both agreed on the choice of Cage and that set the wheels in motion. The result was Cage’s Lecture on the Weather, a work that would eventually be recognized as one of his strongest political statements and most significant works overall.

Richard’s mention of my Wisconsin heritage figures directly in the story: it was thanks to a broadcast on Wisconsin Public Radio in the late 1950s that I first encountered Cage and his music. I was a lad in my pre-teens at the time, and the program I heard featured Cage discussing his Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano. The impact of this listening experience was profound and, I dare say, one that changed me forever. Suffice it to say that my curiosity about contemporary music was thus kindled. Then, in 1974, as a member of CBC Radio Music staff, I had a much closer encounter with Cage while working with Glenn Gould on our series of CBC Radio programs celebrating the music of Arnold Schoenberg. Gould, after interviewing Cage, the former Schoenberg student, via a studio link between Toronto and New York, went on to describe Cage as “Probably the only American composer who’s had any major degree of influence on the European music scene.” He felt Cage “in many ways was the Compleat American Primitive, a sort of musical Thoreau, really, and yet the people on whom his influence was felt the most profoundly were those super organized types like Karlheinz Stockhausen.”

This view, of course, was from a 1974 perspective. It was instructive to have one genius’ point of view regarding the work of another genius, and to see how completely the two contrasted with one another. And in the process, I had plenty of opportunity for hero worship!

One year later, I found myself in the aforementioned consultation with Richard Coulter, who had just been speaking with Austin Clarkson, who was the chair of the music department of York University at that time, about the possibility of CBC Radio staging some of our productions at York. “I recall Austin Clarkson phoning one day,” Coulter says, “to suggest that the CBC believed that music events ended at St. Clair Avenue! He had a point, and that was one of the reasons for mounting the Cage commission at York along with the fact that there was a large American faculty and many US students enrolled then at that institution.”

Clarkson, now professor emeritus, told me that “York staff were delighted to have CBC Radio originate the work with Cage on the York campus. When Cage came for the production the following year, he agreed to meet with York students in their electronic music studio. I came to that session, and it was a wonderful interaction with the students.” (Clarkson added that he always included Cage’s book, Silence, among the texts for his course, a General Introduction to Music.)

The score for Lecture on the Weather (published by the C.F. Peters Corp.), states that the work was “commissioned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in observance of the Bicentennial of the United States of America.” The work is scored for narration, including a preface and 12 amplified speaking parts (preferably to be spoken by 12 US expatriates in Canada), recorded sounds of nature and projected visuals. The texts read by the 12 narrators were derived from three books by Henry David Thoreau, his Essay on Civil Disobedience, Journal and Walden, to which Cage had applied chance operations to determine the precise selections. The 12 narrators were also given moments where they could choose to improvise melodic fragments, either by singing or playing an instrument. Cage enlisted the collaboration of American media artist, Maryanne Amacher to provide the sounds of nature. These included vividly recorded sounds from Walden Pond: first, rain and birds, then wind, and finally thunder. Although it was a commission for radio, Cage nonetheless felt that the visual element was essential for the impact it would have on the live audience. He asked the Argentinian painter and sculptor, Luis Frangella to create the visuals, which consisted of slides of Thoreau’s drawings, chosen with chance operations and projected on a wall in the performance space. The Preface was for spoken delivery by Cage himself.

In that Preface, Cage lays out his thoughts about accepting a commission to observe the US Bicentennial and his reasoning as to how he would respond, given the political realities of 1976. He writes: “The first thing I thought of doing in relation to this work was to find an anthology of American aspirational thought and subject it to chance operations.” But instead, he chose the writings of Thoreau because “reading Thoreau’s Journal I discover any idea I’ve ever had worth its salt.” He speaks about Ralph Waldo Emerson, Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. and their respect for Thoreau’s ideas. He quotes King, in particular, for having said “What we were preparing to do in Montgomery was related to what Thoreau had expressed. We were saying to the white community, ‘We can no longer lend our cooperation to an evil system.’” Cage wrote that he hoped that creating this work, might “give another opportunity for us, whether of one nation or another, to examine again, as Thoreau continually did, ourselves, both as individuals and as members of society, and the world in which we live.”

Cage then turns in the Preface to his process of using chance operations to determine the details of his composition. He says, “It may seem to some that through the use of chance operations I run counter to the spirit of Thoreau (and 76, and revolution for that matter).” But rather, he says, these procedures are a way of “freeing the ego from its taste and memory, its concerns for profit and power, of silencing the ego so that the rest of the world has a chance to enter into the ego’s own experience. We would do well to give up the notion that we alone can keep the world in line, that only we can solve its problems. More than anything else we need communion with everyone. Communion extends beyond borders: it is with one’s enemies also. Thoreau said: ‘The best communion men have is in silence.’”

And finally comes the powerful dedication: “Our political structures no longer fit the circumstances of our lives. Outside the bankrupt cities, we live in Megalopolis which has no geographical limits. I dedicate this work to the USA, that it become just another part of the world, no more, no less.”

As Cage stood and delivered his Preface for the first time, the members of the audience at York University listened, dumbfounded. The usually apolitical John Cage had taken the opportunity to call for real change in the world. And as Lecture on the Weather unfolded, that same audience came to realize that they were the first witnesses to a prescient work, one of lasting significance. Lecture on the Weather was broadcast on the series I produced, Music of Today, on July 4, 1976.

I was fortunate to enjoy many more productions with John Cage, especially after I created the long-running CBC Radio Two series, Two New Hours, in 1978. But the experience of working with him on Lecture on the Weather was perhaps the best way to get to know him, and to establish a long friendship.

David Jaeger is a composer, producer and broadcaster based in Toronto.