Hot Docs 2016 - High Notes

![]() Hot Docs, North America’s pre-eminent festival of Canadian and international documentary films, makes its annual return at various venues in Toronto for its 23rd edition, April 28 through May 8. Below are thumbnail sketches of a random selection of ten films whose subject is music, and one more, De Palma, which sheds light on the role of the composer in the world of cinema. All films but one screen three times. For details go to hotdocs.ca.

Hot Docs, North America’s pre-eminent festival of Canadian and international documentary films, makes its annual return at various venues in Toronto for its 23rd edition, April 28 through May 8. Below are thumbnail sketches of a random selection of ten films whose subject is music, and one more, De Palma, which sheds light on the role of the composer in the world of cinema. All films but one screen three times. For details go to hotdocs.ca.

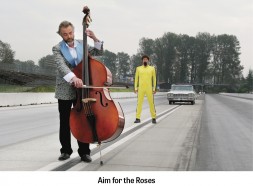

Aim for the Roses is filmmaker John Bolton’s fascinating chronicle of Vancouver bassist/composer Mark Haney’s obsession with daredevil car jumper Ken Carter’s attempt to jump the St. Lawrence River from Morrisburg to Ogden Island, USA, in his modified Lincoln rocket car. Haney spent two and a half years making Aim for the Roses, a concept album devoted to the event. Bolton interweaves vintage footage of Carter with singers performing Haney’s song cycle on the banks of the St. Lawrence, alongside Haney’s own explanation of how he created the piece. (He overlaid 30 tracks of solo double bass playing to produce a super-rich emotionally resonant sound.) Adrian Mack of the Georgia Straight (who’s addicted to the album) calls it “highbrow art and complete trash.”

Aim for the Roses is filmmaker John Bolton’s fascinating chronicle of Vancouver bassist/composer Mark Haney’s obsession with daredevil car jumper Ken Carter’s attempt to jump the St. Lawrence River from Morrisburg to Ogden Island, USA, in his modified Lincoln rocket car. Haney spent two and a half years making Aim for the Roses, a concept album devoted to the event. Bolton interweaves vintage footage of Carter with singers performing Haney’s song cycle on the banks of the St. Lawrence, alongside Haney’s own explanation of how he created the piece. (He overlaid 30 tracks of solo double bass playing to produce a super-rich emotionally resonant sound.) Adrian Mack of the Georgia Straight (who’s addicted to the album) calls it “highbrow art and complete trash.”

Speaking from a grand piano, Jocelyn Morlock, composer-in-residence of the Vancouver Symphony, adds a charming layer to the proceedings, characterizing Haney as “real weird, a real composer, a real renaissance man, quite obsessive and hard working, who wears interesting suits and writes very interesting and distinctive music.” She analyzes Aim for the Roses: “It’s not diatonic but it’s not particularly dissonant. It’s very moody. When you get into the more vocal parts, it straddles the line between alternative pop music and classical. It’s really unclassifiable.” This is a one-of-a-kind documentary.

I Am the Blues is a musical journey through the swamps of the Louisiana Bayou, the juke joints of the Mississippi Delta and the moonshine-soaked BBQs in the North Mississippi Hill Country. It visits the last original blues devils – many in their 80s – who still live in the Deep South and tour the Chitlin’ Circuit. With the legendary (or soon-to-be-legendary) Bobby Rush, Barbara Lynn, Henry Gray, Carol Fran, Little Freddie King, Lazy Lester, Bilbo Walker, Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, RL Boyce, LC Ulmer and Lil’ Buck Sinegal. Director Daniel Cross has produced a valuable time capsule.

When The Revolution Will Not Be Televised premiered at the Berlin Film Festival, The Hollywood Reporter wrote about political and cultural crosscurrents colliding in director Rama Thiaw’s “boisterously engaging documentary, [a] rousing, rap-fuelled dispatch from the west African state of Senegal.” The film chronicles protests against the country’s president through musical resistance led by two charismatic rappers. “The revolution they seek may or may not (in Gil Scott-Heron’s immortal phrase) be televised but it will most certainly be anticipated, described and glorified in their lyrics. Articulate and forceful, they ‘rage against injustice and fight with words,’ providing the most visible and vocal resistance to the powers that be.”

Sonita is a certified crowdpleaser, having won the Audience Award at the world’s largest documentary film festival in Amsterdam and at Sundance (where it was also awarded the Grand Jury Prize). Sonita tells the uplifting story of a courageous young Afghan refugee in Iran, a rapper dedicated to ending forced marriage. She sees herself as the spiritual daughter of Michael Jackson and Rihanna, but her music making and social activism make her vulnerable to religious authority. When her mother tries to bring Sonita back to Afghanistan for an arranged marriage, director Rokhsareh Ghaemmaghami (who spent three years documenting her subject) intervenes and pays off the mother, allowing Sonita’s compelling journey to continue on its path to a fairytale ending.

Contemporary Color: Music maven David Byrne stumbled on the colour guard phenomenon and thought people should know about this high school hybrid of parade-ground drills and athletic dance. With backing from Luminato and the Brooklyn Academy of Music, he commissioned ten composers (including himself) to write original material for an extravaganza of the top colourists which took place at the Air Canada Centre during Luminato 2015. (The material in the film was shot later that year in Brooklyn.) The music is pop-centric, ranging from the sweetness of the femme duo Lucius’ What’s the Use in Crying to Nelly Furtado’s layered hooks and Devonte Hynes’ dreamlike R&B ballad, with St. Vincent’s (Annie Clark) freaky Everyone You Know Will Go Away tapping into teen angst. In fact, the high school vibe is unmistakable in this one-of-a-kind cultural sideshow that marries flag twirling, and the tossing and catching of facsimiles of rifles, with music that romanticizes American adolescence. The experience creates real bonds among the participants, a cross-section of societal groups. The musical highlight was former Philip Glass assistant Nico Muhly’s sophisticated, What Are You Thinking?, which took its post-rock stance seriously, balancing a grounded chamber music centre against a hypnotic percussion groove. A perfect component for what is essentially a high concept reality show.

The Wonderful Kingdom of Papa Alaev: According to Hot Docs programmer Myrocia Watamaniuk, Allo “Papa” Alaev, nearly 80, rules his celebrated folk music clan with an iron tambourine. Beginning with his unilateral decision to emigrate to Israel from Tajikistan, the gifted musician micro-manages nearly every aspect of his family’s lives, both on stage and off. Every child and grandchild lives in their single-family house in Tel Aviv, except his only daughter who chose her own way in life, a sin her father will not forgive. Set to a blazing tribal soundtrack, drama and drumbeats sing out from every entertaining exchange in this grand family affair.

Hip-Hop Evolution: The Banger Films team behind Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey and Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage traces the evolution of hip-hop using Canadian rapper/Q host Shad as a guide and placing the genre’s huge cultural influence in historical context. Director Darby Wheeler told The Fader that Hip-Hop Evolution won’t be a rehash of the genre’s most well-documented moments. “The process [of making the film] revealed some stories that have never received major attention, and we’re hoping that even the most knowledgeable hip-hop heads will be entertained, informed and surprised by what Hip-Hop Evolution has to offer.”

Gary Numan: Android in La La Land shows the electro pop, 80s rocker as family man, dealing with Asperger’s and wondering how he will ever make meaningful music again. With the support of his wife and three daughters, his painstaking studio work on a new album gives him the confidence to go public once again. As Variety pointed out, despite the film’s occasional feel as a glorified promo for the new recording, Numan himself is “winningly candid and guilelessly charming.”

Raving Iran follows two young Iranian men at the centre of Iran’s techno scene as they dodge the authorities and prepare for one giant rave in the desert. As an Italian critic wrote: “The beats of electronic music become synonymous with freedom and healthy rebellion. [Director] Susanne Regina Meures conveys this world suspended between illusion and reality through hypnotic images of bodies letting themselves go to music completely, like in a liberating exorcism.”

Spirit Unforgettable: John Mann, frontman for Canadian Celtic rock band Spirit of the West, faces the reality of early onset Alzheimer’s at 52. With the support of his wife, he and his lifelong bandmates give their fans one goodbye performance at Massey Hall.

De Palma, the indispensable documentary about Brian De Palma, directed by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow, is a candid look at one of Hollywood’s longest directorial careers from the mouth of the man himself. In compulsively watchable detail, De Palma – who considers himself “the one practitioner who took up Hitchcock’s form” – talks about each of his 29 features, dropping one factual nugget after another, from camerawork and direct influences to gossip about famous actors not learning lines, while Baumbach and Paltrow seamlessly intercut scenes from 45 years of filmmaking. De Palma has worked with the cream of film composers, from Bernard Herrmann (“who sees the movie and goes off and writes the score”), John Williams, Danny Elfman, Mark Isham and Ryuichi Sakamoto to Paul Williams (who was able to write parodies of all sorts of pop music forms in Phantom of the Paradise) and eight with Pino Donaggio (Carrie, Dressed to Kill, etc.) and offers several insights into Ennio Morricone’s work on The Untouchables. It all began when De Palma saw Vertigo at Radio City Music Hall as a teenager in 1958.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.