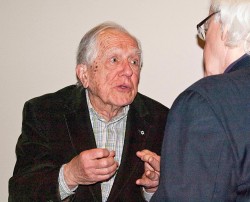

ON SEPTEMBER 19 an enthusiastic crowd gathered in Walter Hall at the University of Toronto for a concert of music by John Beckwith. The setting was appropriate, since Beckwith had spent most of his long career teaching at the university’s Faculty of Music. Before the music got under way, Beckwith sat on stage with New Music Concerts artistic director Robert Aitken to talk about the programme. Aitken, a flutist and composer who had studied with Beckwith, like so many prominent figures in Canadian music, told Beckwith, “I have always looked up to you.”

ON SEPTEMBER 19 an enthusiastic crowd gathered in Walter Hall at the University of Toronto for a concert of music by John Beckwith. The setting was appropriate, since Beckwith had spent most of his long career teaching at the university’s Faculty of Music. Before the music got under way, Beckwith sat on stage with New Music Concerts artistic director Robert Aitken to talk about the programme. Aitken, a flutist and composer who had studied with Beckwith, like so many prominent figures in Canadian music, told Beckwith, “I have always looked up to you.”

Aitken recalled how Beckwith had arrived at one of the first concerts ever put on by New Music Concerts 40 years ago. A snowstorm prevented most people from coming. But Beckwith, with characteristic élan, arrived on cross-country skis.

Now 83 years old, Beckwith was being celebrated not just for his huge body of compositions, or even for the many books he had written and edited, or, for that matter, his lively journalism. It was his unconditional commitment to classical music, contemporary music, and above all, Canadian music that have put him in a class of his own. (Beckwith has a new book coming out by the end of the year honouring his own teacher, John Weinzweig.)

I spoke to Beckwith earlier in September, a few weeks before the concert, at his art-filled Victorian home in the heart of the Annex, a short walk from the university where he studied and taught for so many years, and where his partner, Kathleen McMorrow, is head librarian of the U. of T. Music Library. As I came in, I noticed the bicycle he still uses to get around the city sitting in the front hallway.

Beckwith has written about music for all kinds of publications from academic books and

journals to newspapers, magazines, programme notes, and radio scripts. He speaks much as he writes – with uncommon clarity, elegance, wit, sincerity and passion. We began our conversation by talking about how he started out writing about music.

How did you get involved in music journalism? I had some good models when I was a kid and I was interested in writing. I got into journalism and I picked up a few tricks of the trade when I was quite young. I edited my high school paper and then I wrote for the Varsity when I was at the University of Toronto.

Even though you are always fair, you’re fearlessly candid in your judgments. Where does that come from? I never depended on my earnings from journalism, or from performing, since I was always doing a lot of other things. When I was starting to write reviews for Toronto newspapers, I did a piece about unrest in the ranks of the Toronto Symphony – unhappiness with the working conditions and poor morale. I had a lot of friends in the symphony at that time, and I knew how they were feeling, so I put it in an article. I was called on the carpet by the executive of the musician’s union. But if they had taken away my union card – as they threatened to do – it wouldn’t have been that dire for me.

Is that part of who you are – needing to give your opinion and speak out about what you feel is wrong? When I was working at the CBC, I had a wonderful editor, Wendy Michener, the daughter of the Governor General, Roland Michener. I admired her greatly. But she died so young, which was very sad. She used to say that I had a naturally critical disposition. I guess when things bother me I say so.

Do you see yourself as a spokesman for Canadian music? That’s exaggerating, but what has me expressing some of my criticisms is that people who are perhaps in a better position to, don’t. I think that’s the source of the writing that I’ve done in research areas like Canadian music history. I felt that the musicologically equipped people weren’t looking at our musical past with any interest or care – and somebody ought to. I was doing a little teaching in those areas so I thought, “Well, I can dig in.”

In one of your reviews you talked about dealing with “problems of clarification and advocacy.” That phrase seems to describe your own writing – you’re clarifying, but you’re also advocating at the same time. Trying to draw attention, anyway. There are all these clichés that one still hears about Canadian music, like, “Canada is a young country and our culture hasn’t grown up yet”; or a particular favourite, “Canada’s culture has finally come of age.” This is a lot of nonsense. We have a culture that goes back 300 years at least as an immigrant culture, and thousands of years if you’re talking about our aboriginal culture. So come on! I think of it as an excuse – that Canada is a young country, so what can you expect?

Forty years ago you wrote, “Foreign writers, editors and publishers are appallingly ignorant of Canada’s musical attainments and prefer to remain so.” Have things changed much since then? In some respects, yes. Forty years ago materials on Canadian music were sparse. There were no basic references like the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada, no monographs, few biographies, and just one history, which is very good but only went up to 1914. Now we have a whole library of materials on various aspects of Canadian music. If you want to, you can find out all about it.

What about that controversial article you wrote called About Canadian Music: The P.R. Failure, where you said – You’re throwing all these quotes at me. Maybe some of them I don’t mean anymore.

If that’s the case, it would be very interesting to know why. You wrote, “We clearly live in an age of whammo successes from Les Miserables to Nixon in China, of eclecticism, the so-called ‘new accessibility,’ technologically easy solutions, casual throwaway forms....The younger composers of Canada face the challenge of those whammo successes with their slickness and their bland ‘listener-friendly’ accessibility.” Do you still mean that? This was almost 20 years ago, and now the COC is producing Nixon in China in the spring. Robert Fulford said once that Toronto is where fads go to die. Twenty years after Nixon in China was a whiz-bang success everywhere else, Toronto decides to stage it. Now that Adams has written the piece about Los Alamos [Dr. Atomic], which is a very interesting opera and brilliantly done, the Canadian Opera Company thinks it’s safe to do a John Adams opera. Why don’t they find their own operas? They still have a commission on the books out to James Rolfe, one of our most talented younger composers. I hope they do it - and I hope they don’t apologize for it.

It comes down to what your purpose is in composing – is it to reproduce music that’s already been written, or to express some things in music that haven’t been expressed yet. When I was teaching composition at the university, I looked on it as opening windows of knowledge about what composers have done, so that young composers would see what the possibilities were. If a young doctor suddenly says, “I’m going to find a cure for polio,” they need to know that a cure for polio has already been found. But if they study what’s already been done, they’ll learn from that. If you think you’re going to do something new in music, you should look at what composers of the past have done.

But does that lead to composers today writing things that could have been written one hundred years ago, or even 50 years ago? I remember how I felt when I was starting to form a technique. I wanted to see what the new things were and get a sense of where music was going. This was in the 50s and 60s. We looked at Stockhausen and Berio and we thought, “These are new things. Is that where we’re going to be in 10 or 20 years time?”

Now, if the equivalent today is Arvo Pärt, I’m sorry, I can’t take Pärt seriously. Particularly because he’s now the darling of choral societies, while a lot of contemporary choral literature just gets ignored. I don’t know how many other composers who have written for chorus, as I have, resent that. His pieces are sensitive-sounding in a certain way, and rather easy to rehearse. But they’re simplistic, long and boring. If I were still teaching composition, I would say, “Try to find some models that have a little more substance to them.”

You went to Paris in 1950 to study privately with Nadia Boulanger, but you left early, after one year – were you unhappy with what you were getting from her? No, I got a lot from her. My main reason for not continuing with her was that I couldn’t afford to. I had no money at the time, so I thought I was going to have to head back to Canada. But there was another reason, yes. She was very helpful, and her criticisms were very valuable. But after a year of study with her I felt I was getting to be able to anticipate what she was going to say about what I was doing. Yet it was a wonderful year that I had with her and I admired her greatly.

I was wondering whether it was because you felt more in line with Bach and the Germanic tradition rather than the French. You know, half of her examples were from Bach. In her classes we used to sing Bach cantatas.

In a newspaper obituary you wrote about Otto Joachim recently, you quoted him telling you, “John, there are only two kinds of music – Bach and all the rest.” You wrote that it has become one of your favourite sayings. Who would you send students to listen to today? I really don’t get asked by young composers who they should be listening to. But I used to always go to classical models – even though my music doesn’t sound like Beethoven or Mozart. You’re not going to copy Beethoven or Mozart, but you can see at the very highest level how a composer deals with ideas.

What about later music? I don’t think there’s a great background into what happened earlier in the 20th century – the last works of Stravinsky, and composers of that generation. Webern is kind of forgotten. He was a big watchword in the 50s and 60s. But we don’t get Webern performances now – when was the last time anybody performed his Symphony? And it’s a marvellous piece, a very special piece. These are pieces I think students should know, even if they’re not going to copy them, because they represent achievements.

You grew up in Victoria – was that a predominantly British-influenced musical culture at that time? Yes, I had formal music experience singing in a choir and taking piano lessons. But I missed music classes in school. Our schools didn’t have much in the way of music classes, which a lot of kids have now – a little singing, then in high school nothing. Even in Toronto at that time there were very few high schools where you would get an instrumental music class. That came after World War II, with string programmes and specialized training for music teachers. I regret that I never played a stringed instrument. I tried to play a wind instrument but I wasn’t very good at it.

You are playing the piano in the upcoming concert of your music with New Music Concerts. Have you done much performing in recent years? Not for a while. I did a concert with my son Lawrence on violin a few years ago, but I don’t perform publicly all that much. But I play all the time – I love the piano. When we were in Paris last year I had a little Yamaha upright in the apartment we were staying in, so

You are playing the piano in the upcoming concert of your music with New Music Concerts. Have you done much performing in recent years? Not for a while. I did a concert with my son Lawrence on violin a few years ago, but I don’t perform publicly all that much. But I play all the time – I love the piano. When we were in Paris last year I had a little Yamaha upright in the apartment we were staying in, so

I got the Symphonic Etudes of Schumann out and I practised them. A great piece – I hadn’t done them since I was a student. It was good for me.

Did you dream of becoming a concert pianist when you were young? I practised a lot and I had a wonderful teacher. I wanted to be as good as I could be, and I was pretty good. But I didn’t see my place in the music world as a touring professional pianist.

What about composing? That was more the dream, if you want to talk about dreams. I don’t know if it was exactly a dream, but it was an ambition. A dream, I guess – yes.

Did you know what kind of music you wanted to compose? No, I just had the idea that it had to be something new. But I didn’t know what was new. My idea of new and smart when I was about 16 was Poulenc. Nowadays that sounds very funny.

That’s interesting because Poulenc has such a distinctive voice – a kind of attitude. Yes, an attitude – and I guess I identified with that. But, you see, I didn’t know the big Stravinsky pieces, and I didn’t know Schoenberg. The first time I heard Schoenberg was the famous 1944 broadcast of the Piano Concerto with Edward Steuermann and the NBC Symphony under Stokowski. They fired Stokowski as guest conductor because he put it on that programme. It was too far out then. But it’s a marvellous piece. I was transfixed.

I did have the feeling that whatever I composed would be something that hadn’t been composed before. Of course, that’s an ideal, and my first compositions do sound like music that I had already heard. I was imitative – as almost everybody starting out is, I guess. But then you gradually get so that you can use instruments in a new way or put together sounds that haven’t been put together before.

If you were teaching university today would you encourage students to do that? I think it’s the obvious thing if you’re an artist. If you’re going to learn music from the inside you have to take apart scores, learn how to read them, learn how to sing and play them at sight. A lot of it is grappling with the workings of the music, so going through the difficulties of writing and performing music is the way to get inside. But art isn’t just continuing to create replicas of the kind of art that has always existed. I think that originality and newness are part of what you should be doing in art.

Was Ernest MacMillan a role model? Besides being the most prominent Canadian conductor we’ve ever had, he was involved in composition, education, writing, folk-music research, administration. So he had a tremendous influence. A lot of things wouldn’t have happened the way they happened if it hadn’t been for him. But people don’t realize – memories fade fast.

I’m sensing this also with John Weinzweig now. He had a great influence as well, not as thorough as MacMillan, but particularly in composition and new music. He’s only been dead four years. But I find that his music isn’t being played so much, and people already wonder who he is. Or if they find out who he is, they are not interested.

Is that why you did this new book with Brian Cherney? I hope it will make people curious about his music, so they’ll be persuaded to listen to it and perform it.

You’ve contributed a reminiscence of Weinzweig. I thought that I would like to talk about my relations with him because I knew him very well. We were very close friends. He had his own way of describing his life story and he put his own labels on things that had happened to him. Other people would pick up on his view and depict him the same way. But both Brian and I knew that wasn’t the whole story – his life was more complicated than that. And his music is more complicated than that. I think there are myths out there that you have to cut through. One of the essays calls his music naïve – and in some ways that’s the way it could strike you. He found quite simple solutions to a lot of composing problems. But it’s not so much naïve as sophisticated, complex and full of contradictions.

He was very interesting. He was the first person in Canada to study the 12-tone technique and apply it. It was an influential technique – and it still is. Techniques don’t die. They remain available as resources, and different composers treat them in different ways.

What are you working on now? I have various stray ends of projects and ideas. I don’t get asked to write music so much now, so I work on things that I am interested in and curious about. I started to arrange an orchestra piece of mine for piano four-hands, because a friend and I sometimes play four-hand piano music together. If somebody said to me tomorrow, “I need that piece,” I would get right down to it. But I get so far with it and then I get distracted by something else.

What are you working on now? I have various stray ends of projects and ideas. I don’t get asked to write music so much now, so I work on things that I am interested in and curious about. I started to arrange an orchestra piece of mine for piano four-hands, because a friend and I sometimes play four-hand piano music together. If somebody said to me tomorrow, “I need that piece,” I would get right down to it. But I get so far with it and then I get distracted by something else.

I’ve written a lot of music, and a lot of it never gets played. Today I love it and tomorrow I look at it and think, “What made me think this was any good?” There always comes a point – “Why am I doing this? Nobody is going to play it.” Then I get past that. “I’m curious to see how it will be when it’s finished,” I say, or, “It’s for my own pleasure,” or, “It’s for music.”

What do you mean, for music? So that music doesn’t die.You want to keep it alive. The way you do that is to keep thinking about it and creating new examples.

Couldn’t it be that it’s not that music is dying – it’s that musical values are changing. Perhaps I shouldn’t put it that way. But there’s always been somebody – usually an older person like me – who says, “I don’t know what that is, but it doesn’t sound like music to me”. In the 60s when kids would play rock and roll parents would say, “I don’t know what that is, but it certainly isn’t music.” Somebody said the same thing in the 4th century B.C., about a musician who was misusing the Greek modes. (He laughs.)

The trouble is, no one has really satisfactorily defined what music is and what it can do to us. We all have to use metaphors and verbalize something that is not only intangible but momentary – which is the essence of music. It’s hardly any wonder that composers don’t always agree with each other.

Is there room for everything? The kind of work that I’m doing covers a very narrow margin of what’s going on.

So you need to keep fighting just to maintain that margin? I don’t know about fighting, but adding to the repertoire so that the concept doesn’t die. Maybe that’s it – so you’re doing it for music.

For further information on John Beckwith:

• Weinzweig: Essays on His Life and Music, edited by John Beckwith and Brian Cherney, will be published by Wilfred Laurier University Press in December 2010.

• Information on Beckwith’s life, compositions and writings can be found at the Canadian Music Centre website: www.musiccentre.ca.

• A list of Beckwith’s writings and compositions up to 1994 can be found in Taking a Stand: Essays in Honour of John Beckwith edited by Timothy McGee (University of Toronto Press).

• A biography, comprehensive list of his writings and compositions is included in his entry in the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada: www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com.