Whether they are physical or metaphorical, staircases take us from one place to another through a liminal space. But far from being “non-places”’ that we should take for granted, stairways are also entities unto themselves: they can effect a change in place or fortune, and themselves stand as symbols of class or power. In Staircases, her new production for Tafelmusik, Alison Mackay explores music with direct or inferred links to staircases and, as she puts it herself, builds a case about complex connections between the arts and economic issues.

Whether they are physical or metaphorical, staircases take us from one place to another through a liminal space. But far from being “non-places”’ that we should take for granted, stairways are also entities unto themselves: they can effect a change in place or fortune, and themselves stand as symbols of class or power. In Staircases, her new production for Tafelmusik, Alison Mackay explores music with direct or inferred links to staircases and, as she puts it herself, builds a case about complex connections between the arts and economic issues.

Some of the links are straightforward: Handel’s serenata Parnasso in festa draws a parallel to the physical steps carved into Mount Parnassus; Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum uses the same location as a metaphor for the steps taken to master the technique of fugue. Lully’s comédie-ballet Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme was premiered on the Grand Escalier of the Chateau of Versailles, known as the Ambassadors’ Staircase. But the program delves deeper in its meditation on the associations that stairways can evoke. As Mackay explains, “Most of the staircases in the show are known to have had performances of music on them, and most of them were built by monarchs or merchants who owed much of their wealth to the profits from the trade in human cargo.”

Mackay has often brought in collaborators from beyond the Tafelmusik family for her past projects. This time it is American composer/bass-baritone Jonathan Woody. “He is such a wonderful singer who has performed with Tafelmusik in the past and I also knew him as a composer from other contexts.” Mackay said. “His artistic practice is entwined with his deep understanding of historical issues and his concern for social equity and justice… He also created the spoken narrative which puts his new piece in context, and he has guided me about terminology and choice of language for my own part of the script.”

As Mackay explains, “Both Safe Haven, our concert about the contributions of refugee populations to their new cities, and The Indigo Project, exploring the role of indigo dye in the economy and culture of Baroque Europe, touched on the transatlantic slave trade. I had wanted to go deeper in examining the debt which some of our most beloved works of art and music owed to the proceeds from slavery. This seems so shocking to us now until we consider the extent to which our own bank accounts might be profiting from companies engaged in unethical practices.”

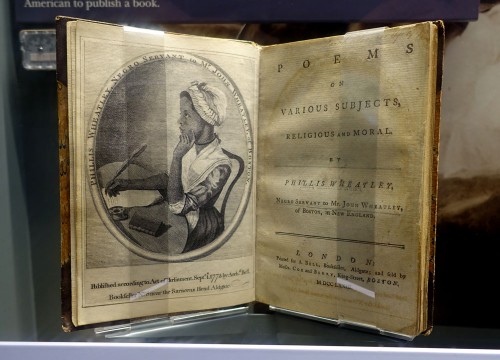

One of Woody’s compositions is a setting of poetry by 18th-century African-American poet Phillis Wheatley. Wheatley was kidnapped as a child in Africa and made a slave in the household of John Wheatley, a Boston businessman. She was, however, excused from servant’s duties and tutored from a young age, attaining a level of education that would have been unusual at the time for a woman of any race. She read Greek and Latin classics by the age of 12; at 20 her collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) was published in London, after which the Wheatleys freed her. Her reputation and achievements spurred on the growing antislavery movement.

From Wheatley’s poem “Imagination,” Woody sets the fourth stanza, “Imagination! Who can sing thy force?”, which celebrates the boundless strength of the human mind. Phillis Wheatley’s writing and publication of this poetry was itself a feat of force and defiance, given her status and gender, and so the choice of text here encourages a mental link between slavery and those who benefitted from it. In this case, Woody and Mackay connect the dots between a staircase on the river Thames that would have been descended by slaves boarding English slaving ships, and the companies whose funds made Handel’s musical productions possible – investments in the South Sea Company and the Royal African Company, both of which were engaged in the slave trade.

Mackay is enthusiastic about bringing present-day relevance to older repertoire. “I particularly love to explore topics that have a place in all our lives: Who were the anonymous papermakers and instrument builders who allowed Bach to realize his musical ideas in a concert? Who are they today? How did refugee newcomers transform the economies of London, Berlin, and Amsterdam around 1700, and how are our lives and our music being similarly transformed in Toronto today?”

It would be possible to enjoy this program purely for its beautiful selections by Baroque musical masters and for the promise of a new exciting work by Woody. But all jokes about Stairway to Heaven aside, this program has the potential to lead those who experience it on their own musico-metaphorical journey. As Mackay puts it, “Staircases, whether they were climbed by the richest or the least powerful in baroque society, made a rich setting for the music as well as for the human dramas that unfolded on them.”

Tafelmusik’s Staircases runs from March 22-24, 2024, at Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul Centre, 427 Bloor St. W.

PERIOD MUSIC ROUNDUP

Rezonance: Always inventive and energizing in its performances, Rezonance Baroque wants to represent 17th- and 18th-century Baroque repertoire with more inclusivity that was formerly found in textbooks. Their upcoming concert, Disappearing Act, will include violin concertos by Joseph Bologne (1745–1799), a black violinist and composer from Guadeloupe who was also known as Chevalier de Saint-Georges; and Maddalena Sirmen (1745–1818), a professional violinist and composer. Also on this program are works by Isabella Leonarda (1620–1704), and Elizabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre (1665–1729).

Rezonance: Always inventive and energizing in its performances, Rezonance Baroque wants to represent 17th- and 18th-century Baroque repertoire with more inclusivity that was formerly found in textbooks. Their upcoming concert, Disappearing Act, will include violin concertos by Joseph Bologne (1745–1799), a black violinist and composer from Guadeloupe who was also known as Chevalier de Saint-Georges; and Maddalena Sirmen (1745–1818), a professional violinist and composer. Also on this program are works by Isabella Leonarda (1620–1704), and Elizabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre (1665–1729).

February 4: Kailey Richards and Erin James, violins; Rezonance Baroque Ensemble. St. David’s Anglican Church, 49 Donlands Ave.

Tafelmusik: Thanks to violinist Aisslinn Nosky’s intelligent and spirited performances, the announcement of her stint as guest director of Tafelmusik is welcome news. She’ll lead the orchestra for Passions Revealed at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre then on the road for a six-city U.S. tour. As the title suggests, it’s a program of music designed to “move the affections,” as was the aim of Baroque composers, and features Nosky as a soloist with Johanna Novom in Bach’s D minor double Violin Concerto.

Tafelmusik: Thanks to violinist Aisslinn Nosky’s intelligent and spirited performances, the announcement of her stint as guest director of Tafelmusik is welcome news. She’ll lead the orchestra for Passions Revealed at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre then on the road for a six-city U.S. tour. As the title suggests, it’s a program of music designed to “move the affections,” as was the aim of Baroque composers, and features Nosky as a soloist with Johanna Novom in Bach’s D minor double Violin Concerto.

February 23 to 25: Trinity-St. Paul Centre, 427 Bloor St. W.

Pergolesi via Stravinsky via the TSO: We can’t help but have a subject position and a point of view, even when trying to play or hear early music in its original form. Stravinsky was more open about this when he reimagined music by Giovanni Pergolesi and others for Diaghalev’s ballet, Pulcinella. He asked, “Should my line of action be dominated by my love or by my respect for his music? Respect alone remains barren, and can never serve as a productive or creative factor.” The result is his fanciful, twentieth-century reworking of 17th- and 18th-century material. Gustavo Gimeno conducts a Toronto Symphony performance that will be recorded for Harmonia Mundi, so come out and cough distinctively for posterity (wink wink).

February 23 to 24: Roy Thomson Hall, 60 Simcoe St. 416-598-3375.

Toronto Consort: Love songs, coded messages of concealment, frothy ditties or high art … renaissance madrigals struck “a precarious balance between intensity and superficiality” (as scholar Rika Maniates wrote). They are great fun to sing but perhaps more wonderful to hear from the mouths of accomplished singers. Paul Jenkins leads The Toronto Consort in this promising and wide-ranging program of intimate vocal music featuring works by Monteverdi, Gesualdo, Tomkins and Gibbons.

Toronto Consort: Love songs, coded messages of concealment, frothy ditties or high art … renaissance madrigals struck “a precarious balance between intensity and superficiality” (as scholar Rika Maniates wrote). They are great fun to sing but perhaps more wonderful to hear from the mouths of accomplished singers. Paul Jenkins leads The Toronto Consort in this promising and wide-ranging program of intimate vocal music featuring works by Monteverdi, Gesualdo, Tomkins and Gibbons.

April 5 and 6: Trinity-St. Paul Centre, 427 Bloor St. W. 416-964-6337.

Stephanie Conn is an ethnomusicologist, writer and editor, and former producer for CBC Radio Music. A member of the ensemble Puirt a Baroque, she has also sung with Tafelmusik and other period ensembles, and is active as a traditional Gaelic singer and piano accompanist in Cape Breton.