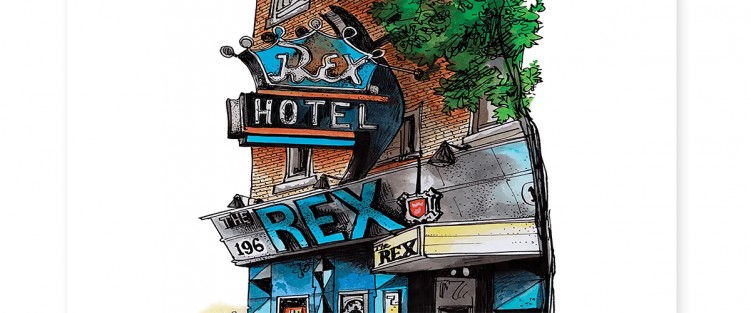

Although not yet as canonically sacrosanct to the history of jazz as NYC’s Minton’s Playhouse was, Toronto’s Rex Hotel is equally important to this city’s jazz community as both a performance venue and a musical testing ground where creative ideas and group concepts germinate and take root.

Although not yet as canonically sacrosanct to the history of jazz as NYC’s Minton’s Playhouse was, Toronto’s Rex Hotel is equally important to this city’s jazz community as both a performance venue and a musical testing ground where creative ideas and group concepts germinate and take root.

Guitarist Lorne Lofsky began playing there with such musicians as saxophonists Bob Mover and Kirk MacDonald and drummer Jerry Fuller in the late 1980s. “It’s really interesting,” he recalls, “to witness the evolution of people’s playing at The Rex. The club is not a laboratory exactly, but rather a magical place where musicians are free to try things out. From that initial experimentation, groups have formed, concepts evolved, and people have grown as players because of the playing that we did there.”

The famed Harlem NYC nightclub, Minton’s Playhouse, existed from 1938 until a fire ripped through the Hotel Cecil that housed it in 1974. It remains an important site to this day, discussed in reverential tones by jazz enthusiasts coming to pay homage at the locale where modern jazz’s equivalents of Zeus, Poseidon and Hades held court. On Monday evenings in the early 1940s, at crowded jam sessions following earlier Apollo Theatre performances, the Olympian“Big Three” were Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Christian.

As much as Minton’s was a place and physical site, it is remembered primarily as a spot of musical experimentation, ultimately becoming the metaphorical petri dish of modern jazz. As the writer Ralph Ellison explained in a 1959 Esquire article, the club’s Monday Celebrity Nights incubated ever-new musical ideas, “allowing the musicians free rein to play whatever they liked.” Yes, there were other spots where this music was developing, but it is safe to say: no Minton’s, no bebop.

Stumbling Serendipitously

Like many “Temples of Sound,” to borrow a phrase from William Clark and Jim Cogan’s great book, The Rex stumbled into its place as a preeminent site of musical excellence not by design necessarily, but rather serendipity – benefitting from the happenstance of proximity, Situated at 194 Queen St W, it was located just down the street from Doug Cole’s Bourbon Street, which in the 1970s and 1980s was bringing marquee name American jazz greats to the city to perform with local rhythm sections. “A lot of musicians who were on break at Bourbon Street would come to The Rex for the cheaper booze and to have a taste between sets” remembers pianist Mark Eisenman, who considers his performances at The Rex as part of trumpeter Sam Noto’s band (with Kirk MacDonald, drummer Bob McLaren and either Neil Swainson or Kieran Overs on bass) as “among his most treasured musical memories.“

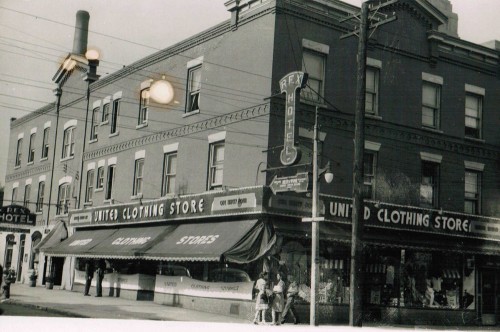

Conversely, Rex owner Bob Ross – whose father Jack and business partner Morris Myers had purchased the former Williams Hotel in 1950 as a “beer hotel” investment opportunity – would cap off his working evenings by going to Bourbon Street to unwind and hear some music. “If it swung, I was into it,” says Ross, who cites performances of Zoot Sims and Jackie Cain and Roy Krall as particularly memorable.

And so, by the early 1980s, a reciprocal ecosystem of musicians moving between Bourbon Street to The Rex Hotel was established. The Ross family business soon went from hosting musicians looking for an inexpensive drink at its bar, to hosting them on the stage that had been built on the hotel’s Queen Street side (previously the United Clothing Store that occupied the southerly portion of the building’s ground floor).

Early and exciting musical sets by saxophonist Jim Heineman and organist John T. Davis, with Mark Hundevad on drums, forged performance ground at the club.

Soon a roster of local players was rotating appearances at the club, including the brothers Lloyd (bassist) and Don “D.T” Thompson (saxophone), pianist Norm Amadio, teenagers Jake Wilkinson (then on valve trombone) and saxophonist Grant Stewart, trombonist Terry Lukiwski and drummer Norman Marshall Villeneuve. The roster also included saxophonist Bob Mover, who, at the behest of long-time Rex server Rob Collins, began living upstairs in the club’s second floor hotel rooms. The running joke was that a fireman’s pole should be installed from Mover’s room directly to the club’s stage.

Both living and playing regularly at The Rex, saxophonist Mover gained insight into not only the musicians who worked the weekend performance slots, but the Damon Runyan-esque characters who fraternized the establishment. Be it the erudite “Stoney” (who would apparently quote Bukowski between sips of a drink), the drummer Norman “Spike” McKendry (who recorded in Montreal with Sadik Hakim), or pianist Jim McBirnie (who was there so often that he had an unofficial bar seat. The Rex was as rich in character as it was in the musical talent it hosted.

“It was a fascinating atmosphere with a lot of soul,” says Mover, “which, for a New Yorker like me was very refreshing in ‘Toronto the good!’”

Looking to expand the club’s weekend performances to include a Tuesday evening set, Ross tapped Villeneuve and Mover to co-lead the club’s now famous and longstanding jam session, currently hosted by bassist Chris Banks. These formative sessions soon afforded young musicians the opportunity to perform regularly, learning from the established masters of this music such as Mover and Villeneuve: the latter consciously modelled his bands’ commitment to “passing it down” after Art Blakey’s Messengers, in a rite of passage as old as the idiom itself.

“It was an amazing time,” remembers trumpeter Jake Wilkinson, who by the early 1990s went from sitting in at the jam sessions to co-leading a group at the club on Wednesday evenings. “I learned a lot during those days,” remembers Wilkinson, who would rehearse after hours in the club’s basement with Mover when the older saxophonist was living upstairs.

Handling Success

As the roster of musicians performing at the club and vying for gigs expanded, so did the responsibility of booking shows. By 1989, Ross brought in Tom Tytel, who had recently earned his bartending licence and whose mother was long-time friends with the Ross family, to assist with bartending, evening managerial duties, and, eventually, booking the music.

Commenting on his, and The Rex’s, track record for not only consistently showcasing top-shelf music but staying in business for some three decades, including COVID shutdowns,Tytel disavows any personal agency. “I don’t claim to know music, good from bad, but I do know what works for The Rex. I trust the people to whom Bob introduced me, and I know enough to get out of the way and stay out of all things creative that happen on the stage.”

As the decades passed and the former upstairs residence rooms flourished as renovated and revamped boutique downtown hotel suites under the watchful eye of Ross’ son Avi, the club’s booking policy expanded from those initial Heineman/Davis weekend slots, to hosting music seven nights a week, often with two or three bands performing multiple sets a night. The Rex is today valued as much for the social cohesion it facilitates within Toronto’s intergenerational and intersectional jazz community as for the destination performance spot it provides for local and out-of-town musicians, as well as fledgling student ensembles from the city’s neighbouring schools.

“It’s a mainstay, for sure,” states saxophonist Mike Murley. “It’s hung in there to not only grow over the years but evolve. I love what’s going on there now as the multi-night performances are somewhat like the old days.”

Murley’s “the old days” hearkens back to an earlier time in Toronto jazz when George’s, Meyer’s Deli, Montreal Bistro, Top o’ the Senator, Bourbon Street and the Bermuda Onion reigned supreme. The Rex’s new booking policy has become a creative catalyst for a new crop of younger players who can now bring visiting players to the city for extended engagements. “Having a four-night run at The Rex to workshop the material before recording with Terri Parker’s Free Spirits was really beneficial in terms of preparing the music and getting a sound together,” suggests bassist Lauren Falls.

Tom Tytel’s booking credo is that “if you leave the cooks alone, they will make you a beautiful gumbo.” The Rex, whether hosting the annual Coltrane Tribute (nearing its 40th anniversary) or showcasing an ever-new crop of diverse and talented young jazz voices, has no plans to stop cooking up enriching and soulful sounds anytime soon.

Andrew Scott is a Toronto-based jazz guitarist (occasional pianist/singer) and professor at Humber College, who contributes regularly to The WholeNote Discoveries record reviews.