Like the “O Fortuna’’ chorus from Orff’s Carmina Burana and the first bars of Rossini’s William Tell Overture, Vivaldi’s Le quattro stagioni (The Four Seasons) has a ubiquitous presence in the soundtrack of our lives via films, television commercials, malls and elevators. Thanks to the desire of audiences to experience these concerti repeatedly, and the ambition of many virtuoso violinists to play them, there are many thousands of recordings to date and countless yearly performances of symphonies all over North America and Europe. In fact, Toronto audiences who were quick enough off the mark will have their next opportunity to hear this classic work revisited on February 7 when Anne-Sophie Mutter and Mutter Virtuosi perform it at Roy Thomson Hall. I will be among them.

Our endless fascination with this set of four violin concerti from Vivaldi’s Opus 8 suggests that, rather than being overplayed as some suggest, perhaps they contain layers of nuance and meaning that are worth unpacking again and again almost 300 years after their creation. First published in Amsterdam in 1725 as part of Vivaldi’s Op.8 Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The Contest between Harmony and Invention), the four concerti known as Le Quattro Stagioni (The Four Seasons) had been composed years before and their manuscripts were already circulating. Vivaldi brought them together for Il cimento, Op.8 and added descriptive sonnets to accompany each of the movements, meant to suggest the characteristic of each season that Vivaldi illustrates in music; these are of unknown authorship but thought to be the work of Vivaldi himself – unlike his music, they are considered to be derivative and not of the highest quality.

The poems refer to not only bucolic details like the murmuring breezes of spring or the songs and dances of fall festivals, but also the shooting of guns and the barking of dogs. (As I sit writing this, the lines in “Winter” (L’inverno) describing “nevi algenti” (freezing snow) and “orrido vento” (horrible wind) speak to me most directly.) Vivaldi himself was, of course, a highly skilled violinist and he had already forged many elements of the style we hear here in his previous violin concerti published as Opus 3, but even in Vivaldi’s time and place the first concerto, “Spring” (La Primavera) was particularly admired, and it became a popular showpiece throughout the 18th century and all over Europe.

On the record

As with all classic works, opinions are divided on which recording of The Four Seasons is best, but with so many to choose from there really is something for everyone — and who dares say which one is more authentic, if I may use that loaded term, or comes closest to expressing Vivaldi’s vision. The historical-performance movement of the last few decades has been divisive for both players and listeners with some claiming it has freed us, others suggesting it fetters. It has, however, reminded us more forcefully of the merely contingent authority held by any score (as Henry Kingsbury put it) and the role that oral tradition plays in the performance of music from any period.

After all, in the 17th century this was new music; meant to “move the affects,” to provoke, excite and challenge its listeners. The performer was a partner with the composer as is the case in all music with an improvisatory element. Playing this music still “takes an act of imagination because the scores leave so many choices open to the players,” as Giovanni Antonini of Il Giardino Armonico has pointed out. His ensemble’s 1993 recording with Enrico Onofri caused a stir when it was released, and I still remember the excitement we all felt at hearing the liberties he took with tempi and the way they attacked some sections almost with abandon. Its verve and physicality offered a very different interpretation than some of the more sedate performances we had heard from larger, modern-instrument symphony orchestras, prompting Alex Ross to write a New Yorker review titled “Violent Vivaldi.”

Some performances experimented even more: in their 2013 London concert, The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment had their orchestral musicians interact with dancers on stage in an attempt to bring the sonnets’ poetic images to life even more tangibly; and on his recording Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi – The Four Seasons, Richter responded to the original Vivaldi concerti with his own interpretations, going far beyond the partnership inherent in improvisation to create some completely new music.

A Cycle of the Sun

Perhaps one of the most audacious and effective interpretations of the piece was Tafelmusik’s 2003 production “The Four Seasons: A Cycle of the Sun,” later documented in the film, The Four Seasons Mosaic. It was conceived by Tafelmusik’s Alison Mackay, who played double bass and violone with the ensemble from 1979 to 2019, and was the springboard to almost two decades’ worth of thought-provoking, challenging and creative productions placing beloved works in the period-music canon into what she called “a new historical and cultural context.” Her Four Seasons, revolving around 1725 when Vivaldi’s Il Cimento was published, brought Tafelmusik’s European-style orchestra on period instruments together with players of the Chinese pipa and Indian sarangi, and Inuit throat singers. The fourth movement, Winter, was newly recomposed by Mychael Danna, an Oscar-winning Canadian composer.

The production went far beyond the token inclusion of instruments from other cultures; instead, it showcases different kinds of virtuosity and different responses to the seasons in a way that respects both Vivaldi’s original and the guest musicians.

Fresh ears

As someone who has long been involved with historically informed performance, singing with Baroque violinist David Greenberg in the ensemble Puirt a Baroque and in choirs such as Tafelmusik and La Chapelle de Quebec among others, I can’t help but favour recordings which strive to approximate the kinds of performances that might have taken place in Vivaldi’s time and are played on historical instruments, with all that they make possible stylistically and sonically. But I am always ready for anything which calls me to hear familiar music in a new way, which is why the February 7 Mutter Virtuosi performance at RTH piqued my curiosity.

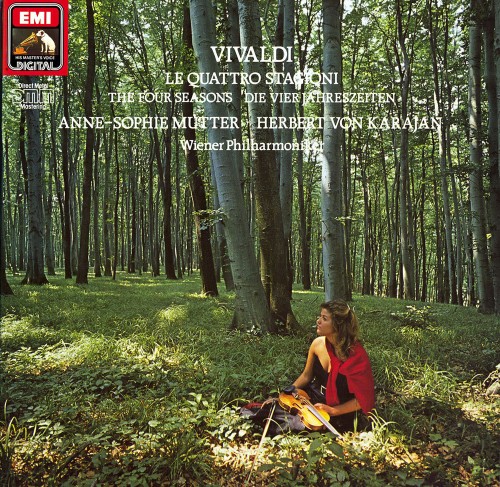

It’s been 39 years since Mutter first recorded Vivaldi’s ‘The Four Seasons’ with Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic on EMI; in 1999, she teamed up with the Trondheim Soloists for a second recording of the work, smaller in scale but still revelling in the lush vibrati and resonance of the modern violin. Even that, however, was 24 years ago now, and it will be interesting to hear how her ideas about these iconic pieces might have changed, and what choices she makes when she has control of the ensemble as well as her solos, as well as getting to choose what musical company the work will keep on the program. Mutter’s February 7 program includes a violin concerto by French Creole composer Joseph Bologne Chevalier de Saint-George (1745-1799), but also the Canadian premiere of a new double violin solo, Gran Cadenza by contemporary Korean composer Unsuk Chin, commissioned by Mutter. With its showcasing of modern virtuosic language it is a fitting accompaniment to the Vivaldi.

Mutter cautions us that “one should not underestimate Antonio [Vivaldi],” yet many do. For his book Conversations with Igor Stravinsky (1959), Robert Craft asked Stravinsky’s opinion of Italian composers and received this response: “Vivaldi is greatly overrated – a dull fellow who could compose the same form so many times over.” What he failed to note, however, is that no piece could possibly be dull that inspires musicians to recreate it over and over in new and innovative ways, and which listeners are always ready to hear. In a recent interview with Mark Wigmore of 96.3FM, Mutter said of The Four Seasons that “you can never get tired of it” and that when she plays it with smaller ensembles like her 14-piece Mutter Virtuosi, “It’s really like a conversation between friends and a lot of spontaneity is possible.”

QUICK PICKS

FEB 12, 2PM: Don Wright Faculty of Music. Opera at Western: Scenes Gala With Early Music Studio. Paul Davenport Theatre, Talbot College, Western University (London).

FEB 19, 3PM: Music at Met. Trinity Bach Project. Vocal and Period Instrument Ensemble. Metropolitan United Church (Toronto).

FEB 23, 7PM: Vesuvius Ensemble. Ninna Nanna: Lullabies from Popular Tradition. Lullabies from Southern Italy. Francesco Pellegrino, voice; Romina Di Gasbarro, storyteller; Lucas Harris, lute & guitar; Louis Simão, accordion & colascione. Heliconian Hall.

FEB 26, 2PM: Toronto Beach Chorale. Vivaldi and the Italian Baroque. Jennifer Krabbe, soprano; Rachel Miller, mezzo; Chamber Orchestra. Beaches Presbyterian Church.

MAR 3, 8PM; MAR 4, 2PM; MAR 5, 3PM: Tafelmusik. Bach’s Library. Francesco Corti, harpsichord & guest director. Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre.

MAR 4, 7:30PM: Kingston Road Village Concert Series. Side by Side Winter Bach #2. Musicians of Toronto Symphony Orchestra; University of Toronto students; Mark Fewer, violin & leader. Kingston Road United Church.

MAR 5, 8PM: Toronto Chamber Choir. The Return of Rosenmuller. Toronto Chamber Choir; Lucas Harris, artistic director. Calvin Presbyterian Church.

MAR 10 & 11, 8PM: Toronto Consort. Canticum Canticorum. Canticorum Trombonorum, performing ensemble. Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre, Jeanne Lamon Hall.

MAR 15, 7:30PM: Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts. Arion Baroque Orchestra: Vivaldi and His Curious Friends. Mathieu Lussier, direction; Samantha Louis-Jean, soprano; Vincent Lauzer, recorder. Jennifer Velva Benjamin Performance Hall, Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts (Kingston).

MAR 23 & MAR 24, 7:30PM; MAR 25, 3:30PM: Tafelmusik. Bach St. John Passion. Ivars Taurins, director. Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre.

MAR 26, 3:30PM: Rezonance Baroque Ensemble. Crossing Borders. Rezan Onen-Lapointe & Kailey Richards, baroque violins; Erika Nielsen, baroque cello; Benjamin Stein, lute & theorbo; David Podgorski, harpsichord. St. David’s Anglican Church.

MAR 28, 7:30PM: Toronto Mendelssohn Choir. Bach: Mass in B Minor, BWV232. Toronto Mendelssohn Choir; Baroque Orchestra; Jean-Sébastien Vallée, conductor. Koerner Hall.

APR 6 & APR 7, 7:30PM: Opera Atelier. Handel: The Resurrection. Carla Huhtanen, soprano (Archangel); Meghan Lindsay, soprano (Mary Magdalene); Alyson McHardy, mezzo (Cleophas); Colin Ainsworth, tenor (St. John); Douglas Williams, bass-baritone (Lucifer) and others. Koerner Hall.

APR 7, 8PM: Georgetown Bach Chorale. The Passion According to St. Matthew. Michael Taylor, tenor (Evangelist); Georgetown Bach Chorale Chamber Choir, Soloists, and Baroque Orchestra. Knox Presbyterian Church (Georgetown).

Stephanie Conn is an ethnomusicologist, writer and editor, and former producer for CBC Radio Music. As a member of the ensemble Puirt a Baroque she sang on the Juno-nominated recording Return of the Wanderer. She has also sung with Tafelmusik, La Chapelle de Québec, Aradia and Sine Nomine, and is active as a traditional Gaelic singer and piano accompanist in Cape Breton.