Once upon a time (the spring of 2021, actually) I made contact with some colleagues and friends known collectively as Pocket Concerts, and individually as Emily Rho and Rory McLeod, interested in knowing how their particular brand, based on house concerts, was holding up in response to the new paradigms of pandemic performance.

Once upon a time (the spring of 2021, actually) I made contact with some colleagues and friends known collectively as Pocket Concerts, and individually as Emily Rho and Rory McLeod, interested in knowing how their particular brand, based on house concerts, was holding up in response to the new paradigms of pandemic performance.

Their biggest news back then was a book in progress, expanding on what they’d learned in developing Pocket Concerts, explaining how other artistic entrepreneurs might get their own ideas off the ground. Envisioned as an online publication, the book was at that point already more than 75% complete.

Life, however, intervened, as it will, and the book has been sidelined. The two remain committed to it, but have each found they have too many other irons in the fire to give it their complete attention. The goals they originally had for it haven’t shifted but life has. As Rho says: “It will take a different shape in the future, I believe, because everything is changing around us so fast, all the time; it’s one thing to put pen to paper, another to find time for the ink to dry… [when] the dust settles … then I think we’ll have more clarity on how to continue.”

Pocket Concerts (PC) fell as hard as the rest of us did, but was probably better positioned than most to rebound, because it specializes in chamber music, presented in homes for small collections of friends and acquaintances of the homeowner. It works in one of a few ways: they can sell entire events to individuals or businesses, or sell individual tickets to a paying public. The venue, provided by a private householder or small business owner, is deemed a donation-in-kind, thus saving PC the expense of a hall rental.

So, like chamber salons of a bygone age, Pocket Concerts take place in settings reminiscent of where and how chamber music was originally offered, with most of the proceeds going directly to the players. Venue providers come away with the feeling of doing something good for the community, and perhaps some social currency, even pride, as well, which seems fair. In existence since 2013, McLeod estimates that during that time they‘ve employed around 120 different musicians (although they stopped keeping track after one hundred). Concerts have taken place before audiences ranging from two to 100, but the typical size was and is still 35 or so. Given indoor restrictions they had to take the show out on the porch (or back deck, or back lawn) over the past two summers, but they managed that without missing a beat.

Weather, however, tends to puts the damper on that type of thing, of course, and last year they began to wonder how to connect directly with the listening community in order to keep live music alive. That’s what the book was going to be for: sharing methods for fostering community, especially among independent musicians whose circumstances have been most severely impacted by the pandemic.

Mind Music: Out of this came “Mind Music” – an idea they got when they took part in a voluntary initiative set up by their friend and colleague Dominique Laplante: she began by asking musicians to take part in interactive zoom meetings, as an outreach project for care home residents who were cut off from so much during the worst days of the lockdown. McLeod and Rho pursued the idea the way they did their live porch concerts, focusing on getting work for freelance musicians who haven’t the benefit of a contracted position with one of the larger, better-funded performance companies.

Mind Music: Out of this came “Mind Music” – an idea they got when they took part in a voluntary initiative set up by their friend and colleague Dominique Laplante: she began by asking musicians to take part in interactive zoom meetings, as an outreach project for care home residents who were cut off from so much during the worst days of the lockdown. McLeod and Rho pursued the idea the way they did their live porch concerts, focusing on getting work for freelance musicians who haven’t the benefit of a contracted position with one of the larger, better-funded performance companies.

Initially, Mind Music was intended to be a one-on-one format: a performer and a listener; part demonstration or recital; part conversation or demonstration. As such, it’s a format suited to, and even designed for remote performance. But the idea grew, with some careful cultivation.

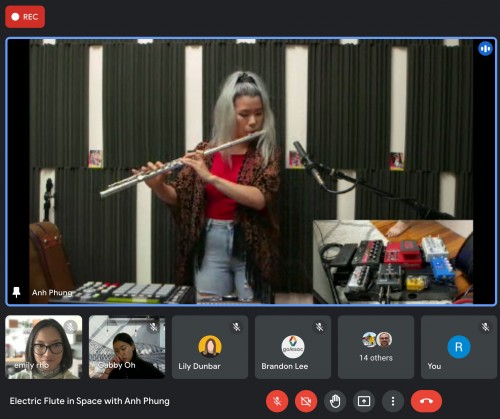

The turning point was when they reached out to businesses, pitching the idea as a perk that might be offered as employee appreciation. TD Bank bought in, and more recently they approached Google’s head office in San Francisco. Google has booked them for a monthly program for this year, creating pocket-sized concert encounters online for Googlers. (Unless you work for Google, you aren’t a Googler, which was among the things I learned in our more recent conversation.) The first Mind Music for Googlers featured Toronto flutist Anh Fung who gave a solo performance with electronics and a beat machine, and followed up with a question-and-answer session.

It seems like an idea that will take hold: in Rho’s estimation, “workplaces are not going back to in-person ever, possibly, so it’s an option to engage with the virtual community in workplaces…” Based on their track record, they are well positioned to offer more as the market for online musical encounters grows. They aren’t in a hurry, though, feeling their way, gauging demand and honing the productions. “One at a time” for a company the size of Google may seem counterintuitive, but it’s how these two work, and it seems to work well.

Scale: The concept of scalability is what most start-ups look to as the holy grail, and sometimes go astray seeking. Get something going, the conventional wisdom says, say like a food delivery app, see if it gets off the ground with a small user base, and then spread the reach. But as Rho and McLeod explained to me back in the spring (and I assume the same is true now), the “products” of their musical entrepreneurship are by definition neither intended nor designed to scale up. It’s like “slow food,” as Rory put it. Absolutely not UberEats, in other words. And they aren’t into hurrying anything, especially not when it comes to building community among audience and performers.

Scale: The concept of scalability is what most start-ups look to as the holy grail, and sometimes go astray seeking. Get something going, the conventional wisdom says, say like a food delivery app, see if it gets off the ground with a small user base, and then spread the reach. But as Rho and McLeod explained to me back in the spring (and I assume the same is true now), the “products” of their musical entrepreneurship are by definition neither intended nor designed to scale up. It’s like “slow food,” as Rory put it. Absolutely not UberEats, in other words. And they aren’t into hurrying anything, especially not when it comes to building community among audience and performers.

So for both of them, connecting with one of the big banks in Canada or a Goliath like Google in the U.S, still comes down to small-scale concerts, interaction at the personal level, and community. Mind Music is now simply offered under the Pocket Concerts brand – a variation of the original idea tailored to online interaction, perfect for small audiences still; featuring primarily solo performers, but going up to small ensembles if buyers want to add to their cost. McLeod and Rho don’t seem to feel pressure to expand the scope or reach of the product. Google has expressed interest in Mind Music for their Toronto Googlers, because the first one was a huge success in San Francisco; the format and scope will remain the same.

The Pocket Concerts story is an ever-unfolding journey with lots of twists and turns. Around the time we first spoke, for example, McLeod was taking courses in editing, which, given their intention to write a book, made perfect sense. Then along came an offer to take the reins as executive artistic director at Xenia concerts. Xenia’s mandate is the elimination of the barriers to musical experience too often encountered by members of the autistic community, and others marginalized by disability. Xenia and McLeod seem made for one another – now, on his current to-do list you’ll also find the completion of a master’s degree in Inclusive Design.

Meanwhile, for her part, Rho is simultaneously pursuing a master’s degree in Strategic Foresight and Innovation, and working with education bodies as a consultant in the same discipline.

Even with their adaptability, it’s not all plain sailing. In our first conversation I recall both expressing the intention to increase access to concert productions for marginalized groups, to improve equity in presenting more BIPOC and LGBTQ artists, and to vary the products they offer to include a wider diversity of musical styles and origins.

The stumbling block, ironically, is that the Pocket Concerts model is consumer driven; the hosts determine what sort of repertoire they want presented. PC can’t insist on presenting musicians and styles beyond the norms of Western Classical Chamber Music, given the baked-in homogeneity of what much of the classical music niche market they serve demands. It’s a problem they are well aware of – till now a fairly silent elephant in the room, a fact that goes from invisible to inescapable, once you admit to it. Regarding Pocket Concerts’ undertaking “to include more BIPOC musicians, more artists from diverse backgrounds” McLeod simply says, “It’s difficult.”

But not impossible. They point to larger musical organizations who are engaged in outreach now: the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre Symphonique de Québec, and Toronto’s Tafelmusik, who, McLeod says, are “reaching new audiences in remote places and from demographics that wouldn’t normally have come to their concerts. That’s exciting to see.”

Will the underprivileged, whether by economic or societal forces, physical or mental disability, or simply by geography, ever be given the kind of access to musical experiences taken for granted by the privileged? Let’s hope so. One bet you can make is that it will come about through the efforts and ideas of people like Rho and McLeod, with their commitment to community, sustainability, and something more valuable than a scalable app.

As for me, I’m still sad about the book being delayed: I was looking forward to writing an article built around clever quotes from the jazz standard “I Could Write a Book” by Rodgers and Hart. That said, it’s been heartening to check in with Rho and McLeod again, to see how much further they’ve gotten along the path toward fostering, by their own actions, a more inclusive, equitable and accessible arts industry. If I ask Rho to consult her strategic foresight crystal ball, I wonder what she’ll see. Foresight and innovation are what this dynamic duo continue to excel in, if I read the evidence right.

Max Christie is a Toronto-based musician and writer. He performs as principal clarinet of the the National Ballet Orchestra when restrictions allow, and otherwise spends too much time on Twitter, @chxamaxhc