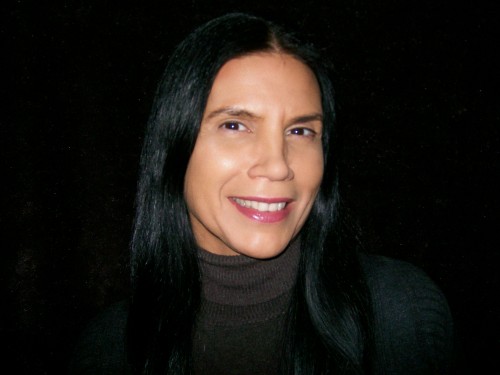

Anyone who witnessed the first concert in June 2001 – a miserable rainy evening with only a handful of people in the audience – might have been forgiven for thinking the Summer Music in the Garden series was doomed to failure. But that first concert didn’t daunt Tamara Bernstein, the founding artistic director of the series. Nor were the audiences deterred. In its 20-year history, the free concert series grew to become one of the most popular on the Toronto summer festival roster.

Anyone who witnessed the first concert in June 2001 – a miserable rainy evening with only a handful of people in the audience – might have been forgiven for thinking the Summer Music in the Garden series was doomed to failure. But that first concert didn’t daunt Tamara Bernstein, the founding artistic director of the series. Nor were the audiences deterred. In its 20-year history, the free concert series grew to become one of the most popular on the Toronto summer festival roster.

By its name, you would think that a venue called the Toronto Music Garden was made for live music, but that wasn’t the case. Perched on the inner harbour of Lake Ontario near the foot of Spadina Avenue, and designed in consultation with famed cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Toronto Music Garden interprets, through the landscape of its six different garden sections, the six movements of J.S. Bach’s Suite No. 1 in G Major for Solo Cello.

It’s an idyllic natural setting with the breezes off the lake and the rustling of the trees, or so it seems, but for some of the performers it could be both a blessing and a curse. Flamenco dancer Esmeralda Enrique, who has been a regular performer there from the early days of Summer Music in the Garden, remembers how challenging those first performances were.

“At first, it was quite difficult technically. Outdoors, the sound dissipates and it’s difficult for musicians and dancers to hear each other, which is vital in live flamenco performances,” said Enrique. “The mist coming in later in the afternoon muffled the sound quite a lot and at times there were a lot of bugs flying around. I remember one flew into my mouth once! Ugh!

“As we came to know the physical limitations and sound level limits, we programmed performances more suited to the environment and temperature,” Enrique explained. “Despite some challenges, I have always loved performing outdoors. In the Music Garden we were inspired by the trees and the wind and felt like they were part of our set.”

The Festival That Almost Wasn’t

Don Shipley was the creative director for performing arts at Harbourfront from 1988 to 2001 and was responsible for starting up the Summer Music in the Garden series and bringing Tamara Bernstein on board to program it.

“I was familiar with Tamara through her writing for The Globe and Mail and I was very impressed by her breadth of knowledge and musical intelligence,” said Shipley. “Her pure love for music was apparent and her interests stretched beyond classical and included contemporary genres. I felt she was the right person at the right time.”

Bernstein recalls how completely out of the blue the call was from Shipley to take on the programming; and how she immediately agreed despite never having done work of that nature or having even gone to the Music Garden. “Once or twice in your life you just say yes to something, and this was one of those times,” she said.

Bernstein cites the way she herself was recruited as an object lesson for how to develop a diverse program and how to find interesting underexposed talent. “It was always in the back of my mind as a programmer that, yes there’ll be pitches from performers, but you always have to look for people who might not contact you,” said Bernstein. “Younger artists and people who might not think of playing at the Garden or who had never even heard of it.”

However, Summer Music in the Garden almost didn’t come to be. Shipley recounts how there was major opposition to having live music in the garden from a condo building nearby, due to noise concerns, and from one condo owner in particular who was very vocal.

“Jim Fleck, who was a major benefactor and fundraiser for the Garden, had the brilliant idea of asking Yo-Yo Ma himself to meet with the condo owner,” recalled Shipley. “So when Yo-Yo Ma was in town to play a concert, arrangements for a meeting and private concert at the condo were made. After that, the opposition magically melted away and the music series went ahead.”

Development of New Works

One of the key contributions Bernstein made to the cultural landscape during her tenure was the commissioning of new works. This enabled artists to explore ideas in a safe and unique space.

One of the key contributions Bernstein made to the cultural landscape during her tenure was the commissioning of new works. This enabled artists to explore ideas in a safe and unique space.

Composer and performer Barbara Croall recalls being invited by Bernstein to compose a new work back in 2008. Titled Calling from Different Directions, it was planned as a commemoration of the 9/11 attack in New York City and the loved ones of those lost.

It was a short, arresting piece invoking the four sacred directions, featuring Croall (cedar flutes and First Nation drum) and Anita McAlister (trumpet and conch shell), and bringing together instruments from different cultural “directions”: trumpet, conch shell, traditional cedar flutes and First Nations hand drum.

“Thinking of the trumpet and its ancestry, I immediately thought of how the conch shell goes back very far in many cultures globally,” said Croall. “Many Indigenous cultures for thousands of years have used it as an instrument of healing through sound. I mentioned this idea to Anita and by a really neat coincidence it turned out that her husband owned a conch shell that was playable and that I could use as one of the instruments in the piece.”

“Tamara was so excited by this idea, and the location of the TMG worked perfectly for Calling From Different Directions, as the sound really carried across the water,” explained Croall.

“Tamara takes great care, sensitivity and detailed planning with everything she does,” Croall continued. “She truly supports the artists that she invites, treating them with respect and kindness.”

All Were Welcome

Another feature of Bernstein’s tenure was the ahead-of-the-curve programming of a range of musical cultures and genres. Although multiculturalism and Indigenous and women artists are featured much more these days, in those early days of Summer Music in the Garden, it wasn’t so usual.

Eric Stein has performed at the Garden for many years both as leader of the Brazilian choro group Tio Chorinho and as the artistic director of the Ashkenaz Festival.

“I’ve always admired the eclecticism of the programming,” said Stein. “And I especially appreciate how, although she maintained classical music as the core genre, she was clever about how she expanded it to other styles of music. Choro is a good example of that as the chamber music of Brazil.”

Classical Persian music, Taiko drumming, traditional Chinese stringed instruments and Indigenous music all had prominent places on the roster next to the Baroque and classical works.

“In 2000, I was totally new to the Toronto music scene,” said tabla player Subhajyoti Guha. “And the performance at the Music Garden gave me immediate access to a mainstream audience which later helped me to build up my career there and also to get students for teaching tabla.

“Tamara always made it a point to present the best of the diverse cultures in her festival and it was a sheer joy for me when she included my band in her festival in 2011.”

Women Rule

Looking back over the rosters of performers during the 20-year history of the music series, it’s striking how many women appeared – not only as performers, but as leaders and composers. From musicians presenting more traditional repertoire such as violinist Erika Raum – who played on the very first evening of the series in 2001 – and cellist Winona Zelenka, to improvisers like pianist Marilyn Lerner and clarinetist Lori Freedman, to Sarangi virtuosa Aruna Saroyan performing North Indian ragas.

“There was an obvious depth of thought Tamara put into the choice of acts and the balance she would strike by including many cultures and lots of female performers, long before it was mandated or popular,” said Eric Stein.

The all-woman Cecilia String Quartet is a prime example. The group played at the Music Garden every year from 2006 until they disbanded at the end of the 2017/2018 season. Violist Caitlin Boyle recalls that it was her first paying gig with the quartet.

The all-woman Cecilia String Quartet is a prime example. The group played at the Music Garden every year from 2006 until they disbanded at the end of the 2017/2018 season. Violist Caitlin Boyle recalls that it was her first paying gig with the quartet.

“As a young musician just graduating, there aren’t tons of opportunities to get paid and recognized,” said Boyle. “And I know within Toronto, Tamara has given chances to many young artists, plus the freedom to choose their repertoire, which isn’t always the case.”

The Future of Music in the Garden

So the big question now is “what’s next?” In these pandemic times, uncertainty is the word of the day, especially when it comes to the performing arts. “We believe that this summer we will not be able to properly gather in large numbers in public places,” said Iris Nemani, chief programming officer for Harbourfront Centre. “So we’ve decided to put our efforts into commissioning new works that we hope will be performed in person in the Music Garden in 2022.

“Tamara has left a legacy of exemplary programming, created opportunities for hundreds of artists and presented beautiful music and dance performances for thousands of patrons,” said Nemani. “Summer Music in the Garden is a beloved, free program and we are looking forward to welcoming audiences back to the Garden next summer.”

Last words go to another contemporary composer whose work has shown up often across the life of the series, Quebec-based Michael Oesterle (although he characterizes his involvement as being more by chance than by design). “It’s not so much that I was specifically commissioned for the series but because musicians invited to perform there already had works by me in their proposed repertoire, and as luck would have it Tamara found the pieces interesting as well. And the feedback I got from those musicians after their performances there was always joyous and positive.

“Some of what Tamara brought to her 20-year tenure,” he continues, “is that she’s intelligent and knows music, but beyond that she is extremely curious, and has found courageous and wonderful ways of drawing audiences into music you might think wouldn’t have a hope in a challenging acoustic environment -- ranging far, but never losing touch with the solo cello intimacy which inspired the place and the series all along.”

“I am sad to hear her time there is at an end.”

Cathy Riches is a self-described Toronto-based recovering singer and ink slinger.