Growing up Canadian, Torontonian and a pianist, the spirit of J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations, as transmuted by Glenn Gould, was ever within my reach. Indeed, for a time, Bach’s masterful set of variations was inextricably linked with Gould, for Canadian and international fans alike. As for me, I was born in the year that Gould died, sharing the same dozen square miles of Toronto for less than six months before his premature death at age 50, in October of 1982.

Growing up Canadian, Torontonian and a pianist, the spirit of J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations, as transmuted by Glenn Gould, was ever within my reach. Indeed, for a time, Bach’s masterful set of variations was inextricably linked with Gould, for Canadian and international fans alike. As for me, I was born in the year that Gould died, sharing the same dozen square miles of Toronto for less than six months before his premature death at age 50, in October of 1982.

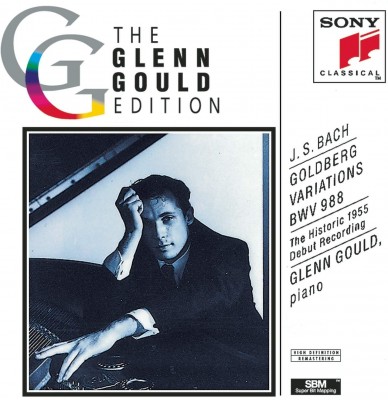

Bach and his keyboard music hovered in the air for many of my generation. At age ten, I had studied the piano for more than five years, and my teacher at the time professed her intense – and seemingly irrational – dislike for all things Gould, (even the lion’s share of his Bach recordings). She, like many immediate contemporaries who knew him personally and scorned his eccentric disposition, proclaimed that little of the late great pianist’s discography was worth listening to. “However,” she conceded, “a handful of recordings remain on the highest order of interpretive genius. His Goldbergs are seminal, you must discover them for yourself – but only the 1955 recording!” “What about the later, 1981 Goldbergs?” I mused to myself. No matter. To the library I went for the 1955 Gould Goldbergs. Beyond the initial awe and insight at the cosmic explication Gould commands on this recording, I was struck that day by a sense of place – a rightness of order or sonic identity – that seemed to be somehow Canadian. True, this was Bach für alle: Bach for all ears that would be lent to it from all corners of the globe, but its origins were oddly local.

Yes I know Gould made that seminal 1955 record in New York City at the Columbia Records 30th Street Studio, but his art, muse and sensibility came from elsewhere, from up north. Suffused with the voice of Bach, how could such musical utterance as Gould’s belong to just one city or country? How does a nation – a collective or an individual even – lay claim to an artist like Gould? How do we honour him and emulate his craft? How close might we get before his essence eludes us?

Yes I know Gould made that seminal 1955 record in New York City at the Columbia Records 30th Street Studio, but his art, muse and sensibility came from elsewhere, from up north. Suffused with the voice of Bach, how could such musical utterance as Gould’s belong to just one city or country? How does a nation – a collective or an individual even – lay claim to an artist like Gould? How do we honour him and emulate his craft? How close might we get before his essence eludes us?

In the more than 25 years since that first day I heard Gould play the Goldbergs, I’ve sought elucidation, a solution or some clue to this state of identity. Gould’s spectral footsteps outwit us constantly. He came amongst us but never lingered long. He followed pathways from different planes, singing tunes from alternate dimensions. The Goldbergs were, it seems, his beginning and his end. A stabilizing force in his life, air under artistic wings spread wide, they launched his performing career. Repaying Bach handsomely, Gould often returned, almost devotionally, to the work. It is through tracing this committed relationship to such a canonic masterstroke, that the trail begins to appear. One can track the residual energy left behind. Much like the Large Hadron Collider creating new, traceable particles that dissipate in highly complex ways as they traverse space, leaving recordable streaks of light now dancing, now repelling, we can pick up the path Gould and his Goldbergs traced, by connecting its points of musical light.

Numerous artists, world-wide, have approached the grail that is Bach’s Goldberg Variations since Gould, lining up to scale the music’s “Everest-like” heights – a perfect musical fusion of an external challenge and an internal quest.

And for us Canadians? We adore Bach and we adore Gould – at least most of us! – along with those fans from many other corners of the world. Here in Toronto, we have the benefit of knowing those who knew him. We can still eat scrambled eggs in a booth at Fran’s Restaurant (although Gould’s local Fran’s is no longer with us). We can drive past Wawa, Ontario and think of his love for the North – for the idea of North. We hear the opening Goldberg Aria vividly in our dreams and in waking hours, sometimes unexpectedly. It is music that captured the world’s imagination, but the hearts of Canadians. It was Eric Friesen, in 2002, who first suggested this tune to serve as an unofficial national anthem.

No artist I know ever approaches the Goldbergs without extreme reverence. There are those who grow up with the work as constant companion. Some, like Simone Dinnerstein, emulate Gould in proving themselves to be up to the mighty task of expressing something wholly new in their performances. Others arrange it for non-keyboard instruments, such as string quartet or the harp (harpist Parker Ramsay’s recently released Goldbergs recording is in fact reviewed by Terry Robbins in this issue’s Strings Attached).

And then there are those like my harpsichord teacher at the Glenn Gould School, the brilliant Charlotte Nediger, who steadfastly refused to perform these variations in public (despite multiple requests for her to do so), humbled, she would say, by its greatness and its formidable roster of past interpreters. Nediger reserved for herself a place so sacrosanct for this music that its appreciation was a purely private affair: a communion of sorts with Bach and Bach alone. Her steadfast refusal struck me at the time as being wholly Canadian in its reverence for this music, deferring to a performance tradition that Gould started, now inherited by pianists such as Angela Hewitt and David Jalbert, and a seemingly endless succession of others seeking to ascend its heights. (The WholeNote has, to date, reviewed 22 recordings of the Goldbergs, more than any other work.)

And then there are those like my harpsichord teacher at the Glenn Gould School, the brilliant Charlotte Nediger, who steadfastly refused to perform these variations in public (despite multiple requests for her to do so), humbled, she would say, by its greatness and its formidable roster of past interpreters. Nediger reserved for herself a place so sacrosanct for this music that its appreciation was a purely private affair: a communion of sorts with Bach and Bach alone. Her steadfast refusal struck me at the time as being wholly Canadian in its reverence for this music, deferring to a performance tradition that Gould started, now inherited by pianists such as Angela Hewitt and David Jalbert, and a seemingly endless succession of others seeking to ascend its heights. (The WholeNote has, to date, reviewed 22 recordings of the Goldbergs, more than any other work.)

An extraordinary aspect of Bach’s Goldberg Variations is the way it adapts itself to the interpreter at hand – the individual experience of this music converges with the collective one: a formidable interpretive, intellectual and technical task for any musician, but also demanding personal expression, in a sense entwining the performer who is playing them. Indeed, This aspect of the journey – or the epic Everest climb – was an integral part of the Goldbergs and their legacy, even before Gould’s 1955 rendering. (Consider Landowska, Rudolf Serkin, Tureck and Kirkpatrick’s early recordings.) It is the work’s invitation to make it an individual statement that still has us lining up as musicians to ascend its heights, and perhaps plant a flag there that some collective other will claim as their own.

An extraordinary aspect of Bach’s Goldberg Variations is the way it adapts itself to the interpreter at hand – the individual experience of this music converges with the collective one: a formidable interpretive, intellectual and technical task for any musician, but also demanding personal expression, in a sense entwining the performer who is playing them. Indeed, This aspect of the journey – or the epic Everest climb – was an integral part of the Goldbergs and their legacy, even before Gould’s 1955 rendering. (Consider Landowska, Rudolf Serkin, Tureck and Kirkpatrick’s early recordings.) It is the work’s invitation to make it an individual statement that still has us lining up as musicians to ascend its heights, and perhaps plant a flag there that some collective other will claim as their own.

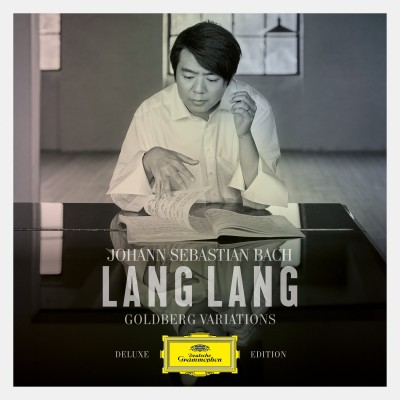

Lang Lang on the Goldberg trail

Lang Lang on the Goldberg trail

Recently, piano icon Lang Lang “realized a lifelong dream” and recorded not one but two versions of the Goldbergs. The first is a one-take, live performance from a recital at Thomaskirche in Leipzig. The second, recorded soon after in studio, was made in seclusion.

I was full of curiosity to hear Lang’s Goldbergs and was certain he must have brooded on the project for a while and approached it with careful consideration, aware of the extent to which it would be a departure for him in many ways, and would be scrutinized by the numerous discerning ears that know – almost by heart – the interpretations that have come before his.

At once, we notice Lang’s personal brand in this recording. He is singing from his beating heart and occupies a seemingly new space in this music. An individual kind of phrasing unspools, buoyed by unusual contrapuntal directionality and dynamic scope. His awareness of previous performance practice is sometimes notable and sometimes not. Nevertheless, he won’t let us perceive it as a hindrance in either direction: the listener is offered new glimpses of what J.S. Bach in the 21st century might be. Even at times where he pushes the historically accurate performance envelope, he remains convincing – his customary demeanour of endless elan and visceral expressiveness a reassurance.

At once, we notice Lang’s personal brand in this recording. He is singing from his beating heart and occupies a seemingly new space in this music. An individual kind of phrasing unspools, buoyed by unusual contrapuntal directionality and dynamic scope. His awareness of previous performance practice is sometimes notable and sometimes not. Nevertheless, he won’t let us perceive it as a hindrance in either direction: the listener is offered new glimpses of what J.S. Bach in the 21st century might be. Even at times where he pushes the historically accurate performance envelope, he remains convincing – his customary demeanour of endless elan and visceral expressiveness a reassurance.

Underlying Lang’s individual approach to the Goldbergs, there is a bedrock of reference to those greats that came before him. For example: he has Peter Serkin’s delicacies in his ears, Gould’s formalism on his mind and Perahia’s precision in his heart. Some of his variations build upon preconceptions in performance practice, likely accumulated from those who came before. And then there are other moments, free and searching, springing forth with freshness and elation. He swims his way through this familiar music, taking it all in as a snorkeller does the first time he dips beneath the water’s surface: all is bright and beautiful, strange and luminous, experienced and expressed only by the swimmer and not by, or for, anyone else.

Lang’s aquatic ecosystem is not without murk nor weed however, and at times he seems entrapped by microcosms of harmony or crossing of musical line. Occasionally, some thorny bit of coral gets tossed out of place but we are still along for the ride, convinced nonetheless. There is voyeuristic delight in the pianist cherishing his special designs; one can be charmed by the novelty on display. It’s as if Lang were discovering some of this music for the first time. He knows just how to turn in the water for us, just which treasures to reveal. As he shapes and cajoles the magnificent Goldbergs, a confidence and focus emerge that is by turns curious and admirable, and eventually, beguiling.

From our vantage point in 2020, we have as many ways to access this music as there are notes in Bach’s score and, increasingly, as there are artists who record the work. One must find their own catalogue of access points, as listener and as artist. Lang has clearly found his. Born of an international sense of Bach and the world’s collective appreciation for this music, Lang leads us on a journey to a highly individual state of being – but one with which we can identify.

In the before time, when I was travelling or living abroad and began to miss my own home, it was Gould’s 1955 recording of the Goldbergs that I turned to, not to OCanada as an anthem It was Gould and Bach that offered me a sense of place as few other pieces could. I used to think such sentiments were germane to a large northern American country with a small, friendly population who claimed an artist, Glenn Gould, to be their own. I don’t think that now. Lang Lang’s new Goldberg recording is a case in point for finding your way home musically and understanding better the many access points that can get you there, wherever there may be.

Concert Note: At time of going to press, American superstar organist, Cameron Carpenter, was scheduled to perform The Goldbergs at Koerner Hall on November 7 on his Marshall & Ogletree mobile, digitized, International Touring Organ, the culmination of a decade-long project for the organist, and now the exclusive organ on which he performs. According to Carpenter’s website, the instrument follows the musical and design influences of American municipal pipe organs from about 1895 to 1950 – organs built to support a vast range of classical and popular playing styles in concert halls, theatres and other public venues. It can be installed at a concert venue in three to five hours by its crew. The November 7 concert marks Carpenter’s return to Koerner Hall after his first appearance in 2016, the same year his Sony CD, All You Need Is Bach, was released.

Concert Note: At time of going to press, American superstar organist, Cameron Carpenter, was scheduled to perform The Goldbergs at Koerner Hall on November 7 on his Marshall & Ogletree mobile, digitized, International Touring Organ, the culmination of a decade-long project for the organist, and now the exclusive organ on which he performs. According to Carpenter’s website, the instrument follows the musical and design influences of American municipal pipe organs from about 1895 to 1950 – organs built to support a vast range of classical and popular playing styles in concert halls, theatres and other public venues. It can be installed at a concert venue in three to five hours by its crew. The November 7 concert marks Carpenter’s return to Koerner Hall after his first appearance in 2016, the same year his Sony CD, All You Need Is Bach, was released.