For many North American orchestras, playing in the pit for ballet performances of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker is a common holiday tradition. This was my experience, first as a clarinetist and then as an orchestra librarian. My first encounter with Messiah as a professional, however, was during my interview for the librarian position of the Phoenix Symphony when I was asked, “What edition do you like for the Messiah?” It is an extraordinarily complex question – much more so than I would have known at the time. I managed to offer up something I’d learned from a couple of sing-along Messiahs I had attended – the organizer cautioning the audience/performers about the different numbering systems in various publications. But over the succeeding 30 years I have learned that there is much more to it than that, as I hope to share with you in this article.

For many North American orchestras, playing in the pit for ballet performances of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker is a common holiday tradition. This was my experience, first as a clarinetist and then as an orchestra librarian. My first encounter with Messiah as a professional, however, was during my interview for the librarian position of the Phoenix Symphony when I was asked, “What edition do you like for the Messiah?” It is an extraordinarily complex question – much more so than I would have known at the time. I managed to offer up something I’d learned from a couple of sing-along Messiahs I had attended – the organizer cautioning the audience/performers about the different numbering systems in various publications. But over the succeeding 30 years I have learned that there is much more to it than that, as I hope to share with you in this article.

The complexity begins with the fact that George Frideric Handel was a German who spent the last 49 years of his life in London and achieved his greatest successes there. He composed Messiah – in English – in 1742 and, over the next several years, conducted it 13 times. As might be expected, these performances featured varying casts of vocal soloists, so during those years Handel rewrote several of the solo pieces to better suit these different voices. With its extraordinary popularity (and copyright protection still in its infancy) came many publications of the music, each with its own system of organizing and numbering the content. Moreover, because of its timeless story and memorable tunes, Messiah became the object of updates by several composers (including Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart) who made new orchestrations to capture an expressive sonority more in keeping with their time. The TSO’s own Sir Andrew Davis is the most recent example of this.

Let’s pause right here to consider the things that could go wrong at a first rehearsal. The conductor might ask for “No. 44,” at which the chorus (reading from the Watkins Shaw edition) would sing, “Hallelujah!” while the alto and tenor soloists (reading from the Bärenreiter edition of the Handel version) would launch into “O Death, Where is Thy Sting?” and the orchestra (reading from Bärenreiter parts of the Mozart version) would chime in, “We don’t have a number 44!” Even worse, the additional flutes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trombones, tuba and percussion (variously required for versions by Mozart, Prout, Beecham or Davis) might not even show up! There are, in fact, so many performance variables that it really is necessary for each conductor to have a set of parts marked to his or her specifications.

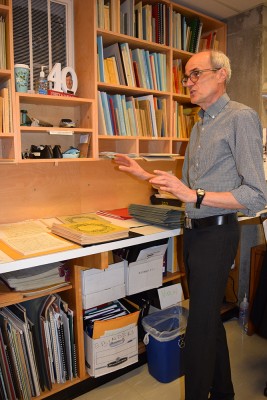

I got that that first library job in Phoenix, and that fall was presented with a score of Messiah into which the conductor had entered thousands of performance indications, which I was obliged to transfer into the parts (first ensuring, of course, that the soloists, chorus and orchestra would all be performing from that same edition). It took a couple weeks of constant work, but I vividly remember the conductor’s delight when he came to the library, opened the second violin part to a particular page and found his performance instructions copied there.

Long before there was a Toronto Symphony, choral music was the dominant force in this city’s musical life. The first performance of Handel’s Messiah in Toronto took place in February 1873 and the founding of the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir predates that of the Toronto Symphony by some 28 years. In his history of the Toronto Symphony, Begins with the Oboe, Richard Warren suggests that it was the desire for a better orchestra to accompany oratorio performances that was partly responsible for the formation of a regular orchestra. The TSO and TMC collaborated to perform Messiah first in 1936, again in 1948 and have done so nearly every Christmas season since.

Messiah at the TSO

When I arrived for my first day at the Toronto Symphony in January 1992, I was greeted by a menacingly sizable pile of eraser bits on a corner of my new workstation – the remains of the TSO’s most recent performance of Messiah. At the same time, I learned that we would be performing it every year. And only a few weeks later, while sorting through old files, I came across a newspaper article about one of my predecessors, John Van Vugt, Librarian for the Toronto Symphony from 1923 to 1967. The title, in large bold letters was, “Toronto Symphony Librarian Has Nightmares.” It made for a somewhat ominous beginning.

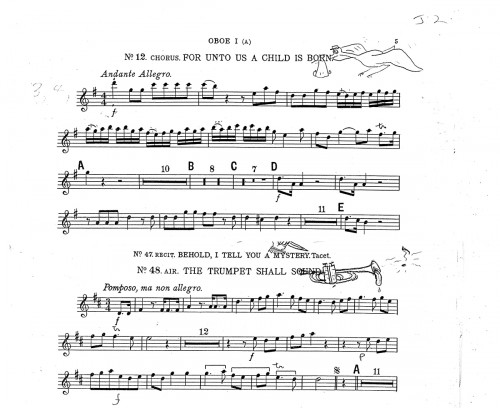

I should say, however, that my experiences with Messiah at the TSO have not always been difficult. On several occasions, for instance, Elmer Iseler, director of the TMC, led our performances using a set of parts that had been marked and remained unchanged for many years. “Unchanged,” I should say, except for an accumulation of cartoons drawn in the first oboe part by our former principal oboe, Perry Bauman.

This year is less routine. The TSO has engaged Alexander Shelley, music director of the National Arts Centre Orchestra, to conduct Mozart’s orchestration of Messiah. This eliminates a wide range of issues, but by no means all. Mozart’s Messiah is originally sung in German. Shelley wants English, but his preferred edition (Bärenreiter) does not produce a score with English text. For the chorus, this is no problem, since the choruses retain the same music and bar count as Handel’s original. TMC members can read from their familiar parts with a list that converts the Bärenreiter numbers to Watkins Shaw. Parts for the vocal soloists are, however, more complicated. Mozart chose some of Handel’s standard voice assignments, but also some of his optional ones. Most of these can be taken from the original Handel vocal score and its Appendix. So far, so good – until you get to an alto aria reassigned to the bass (the clef doesn’t work) or “The Trumpet Shall Sound” in which measures are deftly omitted, and the whole is rescored with horns taking prominence. In these cases, it was necessary to replace the German text with English in the Mozart vocal score. Sometimes matching the syllables is quite a challenge.

The TSO’s principal trombone, Gord Wolfe, had no idea what he was getting into when he first encountered the Mozart Messiah – in more ways than one.

In keeping with the orchestras of his time, Mozart augmented Handel’s instrumentation by two flutes, two clarinets, one bassoon, two horns and three trombones, so players who might usually have enjoyed an extra holiday week are obliged to work. Trombones appear in only three short movements of the full score, however it was the performance practice of Mozart’s time that the three trombones would reinforce the alto, tenor and bass voices in all the choruses. Only a remark in the critical commentary, printed in a separate volume of the Bärenreiter edition, points to this. Bärenreiter doesn’t even print complete trombone parts. Quite ironically, the “trombone” does appear in the German title of “The Trumpet Shall Sound,” [Sie schallt, die Posaun’]. (In the German tradition, the trombone is the instrument of the last judgment, and Mozart would again use it as such in his Requiem.)

Messiah is, as Elmer Iseler was fond of saying, a “big sing” for the chorus and nobody knew that better than Gord at the end of the first rehearsal. As he looked skyward in exhaustion, his eyes wandered over to the choir loft where Stephanie Fung, an alto in the TMC who was also singing her first Mozart Messiah, happened to be looking back. “Oh, she’s cute,” Gord thought to himself. He looked for her on the subway, but she was living in Markham at the time and had driven. By some electronic holiday miracle, they booked a coffee before the final concert – and then agreed to a drink afterward. That was 13 years ago – the last time the TSO performed the Mozart Messiah. Steph and Gord got married in 2009 so in performing together again in these concerts they are celebrating the anniversary of their meeting.

On the topic of “Orchestra Librarian Nightmares,” next month the TSO will be giving four performances of Mozart’s Requiem - a work left unfinished at Mozart’s death and which exists in completed versions by Süssmayr, Robbins Landon, Beyer, Maunder, Levin, and Druce. If you want to see and hear how it goes – the Süssmayr version, that is – come to Roy Thomson Hall on January 15,16,17 or 18, 2020: tso.ca/concerts.

Gary Corrin is principal librarian of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, would-be scholar and eternal romantic. He met his wife, Ingrid Martin, a soprano with the Canadian Opera Company Chorus, at “Bravissimo!” the annual New Year’s Eve opera gala at RTH – but that’s another story.

Gary Corrin is principal librarian of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, would-be scholar and eternal romantic. He met his wife, Ingrid Martin, a soprano with the Canadian Opera Company Chorus, at “Bravissimo!” the annual New Year’s Eve opera gala at RTH – but that’s another story.

God is in the Trombone

The trombone is said to have been invented in the middle of the 15th century, but until the 18th century was called a “saqueboute” (in French) or a “sackbut” (in English). Originally it was closely associated with Christian church music and for this reason was often used to symbolize God or supernatural phenomena when it began to be used for other kinds of music during the 18th century. Mozart is said to have picked up on this from Gluck and Salieri. In the impressive solo at the end of Mozart’s Requiem, the trombone announces the Last Judgment. And when Don Giovanni is sent to hell for his life of debauchery, the trombone is used to portray a supernatural force that reaches beyond human intellect. In Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony the trombone represents the powerlessness of man in the face of nature during the fourth movement which depicts a thunderstorm, and in the fifth movement the trombone voices mankind’s gratitude toward God.

The trombone is said to have been invented in the middle of the 15th century, but until the 18th century was called a “saqueboute” (in French) or a “sackbut” (in English). Originally it was closely associated with Christian church music and for this reason was often used to symbolize God or supernatural phenomena when it began to be used for other kinds of music during the 18th century. Mozart is said to have picked up on this from Gluck and Salieri. In the impressive solo at the end of Mozart’s Requiem, the trombone announces the Last Judgment. And when Don Giovanni is sent to hell for his life of debauchery, the trombone is used to portray a supernatural force that reaches beyond human intellect. In Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony the trombone represents the powerlessness of man in the face of nature during the fourth movement which depicts a thunderstorm, and in the fifth movement the trombone voices mankind’s gratitude toward God.