The historic trade routes collectively referred to as the Silk Road, an interconnected web of maritime and overland pathways, have, for centuries, served as sites for cultural, economic, educational, religious – and purely musical – exchanges. In that light, “silk roads” can be seen as a significant factor in the development of the ever-evolving hybridities that have shaped the face of the modern musical world.

The historic trade routes collectively referred to as the Silk Road, an interconnected web of maritime and overland pathways, have, for centuries, served as sites for cultural, economic, educational, religious – and purely musical – exchanges. In that light, “silk roads” can be seen as a significant factor in the development of the ever-evolving hybridities that have shaped the face of the modern musical world.

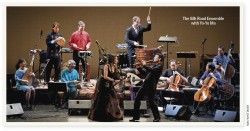

In 1998 the Grammy Award-winning cellist Yo-Yo Ma proposed “Silkroad” as the name of his new non-profit organisation. That project, inspired by his global curiosity and eagerness to forge connections across cultures, disciplines and generations, has grown several branches, the first of which was the successful music performing group, Silk Road Ensemble (SRE). It has played to sold-out houses at Roy Thomson Hall in 2003 and 2009 and will return to perform at Massey Hall on September 15. (Serendipitously, Toronto audiences will have another opportunity to see the SRE up close this September. Morgan Neville’s feature-length documentary The Music of Strangers: Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble graces TIFF’s red carpet, enjoying its world premiere.)

Wu Man’s view from the pipa. Chinese-born Grammy Award nominee Wu Man, widely hailed as the world’s premier pipa (Chinese lute) virtuoso, has a unique perspective on the SRE’s career. An educator, composer and an ambassador of Chinese music, she has a prolific discography of 40 albums and counting. She was among the first musicians to get the call from Yo-Yo Ma to help in founding SRE.

We spoke by phone on August 14. “It was actually in 1998, even before we officially announced the ensemble in 2000 at Tanglewood [the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer festival home]. Of course many other musicians have joined us since then.”

Asked about her early encounters with Western classical music and musicians, Wu recounted her first live exposure as a young student. “In 1979 I saw Seiji Ozawa conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra performing in Beijing. At the time I was still a pipa student at the Central Conservatory of Music” (where she became the first recipient of a master’s degree in pipa). The Boston Symphony, she explains, was “conducted by a charismatic Asian conductor, so the hall was packed with curious people from across the county: it wasn’t easy to get a ticket. The music played that night proved to be a revelation to me and my classmates.”

Her next Western musical encounter came a year later. “I participated in an inspiring Beijing masterclass with violinist Isaac Stern.” (The 1980 Academy Award winning documentary film From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China provides insight into the great maestro’s groundbreaking tour.)

These two musical experiences proved to be pivotal influences in Wu’s subsequent professional music career in the West, launched when she moved to the U.S. in 1990. They also undoubtedly played a role in her eagerness to be among the SRE founders.

How does she respond to concerns some have around cultural appropriation? “I’d have to say that there’s nothing ‘pure’ in a given culture – or in a national state for that matter – as illustrated for instance by the box we may label ‘China.’ When we can equitably share cultures however, it puts us in a much bigger [and more inclusive] box called ‘the world.’”

Wu’s 2012 Borderlands CD/DVD, co-produced by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Culture Heritage, traces the history of the pipa in China. Its narrative also speaks to the primary mission of the SRE. “My instrument’s roots extend to Persia 1,000 years ago, but its origins had largely been forgotten in China,” she noted. It was only through the SRE, working with Central and South Asian musicians, that “I became aware of the commonalities between many plucked string instruments and their performance methods. Only then was I able to appreciate our common roots. I feel that only if you know your roots can you then imagine how to create something new.”

Above all, Wu Man takes very seriously her responsibility “to represent the pipa to the audience, most of whom have never seen or heard it live.” The pipa, she says, is the musical vehicle which she uses to “bridge many cultures. This is my mission. In recent years I’ve gone back quite often to give masterclasses at Chinese music schools.” Her rediscovery, embrace and showcasing of the musical traditions of her birthplace, projects she has titled her “Return to the East,” are often expressed in stage appearances with the SRE. They can also be seen as completing the circle Ozawa and Stern’s example modelled for the young pipa student in Beijing nearly two generations ago.

Behind the Cello.“Behind the Cello,” published January 21, 2014, is a wide-ranging and penetrating Huffington Post article I found, adapted from a conversation Ma had with WorldPost. In it Ma talks about having founded the Silk Road Project “to study the flow of ideas among the many cultures between the Mediterranean and the Pacific over several thousand years.”

Behind the Cello.“Behind the Cello,” published January 21, 2014, is a wide-ranging and penetrating Huffington Post article I found, adapted from a conversation Ma had with WorldPost. In it Ma talks about having founded the Silk Road Project “to study the flow of ideas among the many cultures between the Mediterranean and the Pacific over several thousand years.”

The silk road as a useful and enduring metaphor for exploration of intersecting and cross-pollinating musical routes has served other musicians and ensembles well over time, but it is particularly well suited to Ma’s capacious intellectual curiosity, encrusted as it is with historic and personal echoes. As he and his travelling companions in the SRE continue to experiment with these ideas, on stage and in the larger social project these performances are encased in, the metaphor takes on greater and greater resonance. Positive audience response to the SRE’s always musically engaging concert performances have given the groups a special niche on world stages. Beyond that, in my view, the group is also operating at the leading edge of the evolution of a greater pan-cultural musical consciousness in the 21st century. Let’s explore some of these grand assertions.

While making music is SRE’s essential mission, Ma’s vision for the group as stated in his “Behind the Cello” interview is no less than to bring “the world together on one stage.” Calling SRE’s musicians a “peer group of virtuosos, masters of living traditions,” he has enlisted European, Arabic, Azeri, Armenian, Persian, Russian, Central Asian, Indian, Mongolian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese participants into its ranks. The group modus operandi entails generous sharing of received knowledge, curiosity about other forms of expressions and a reciprocal keenness to learn from each other. That much is evident to audiences attending live SRE concerts or one of its workshops, and even to those casually flipping through YouTube videos.

Ma argues that invention and evolution hand-in-hand hold the keys to cultural engagement and growth: “... we have found that every tradition is the result of successful invention. One of the best ways to ensure the survival of traditions is by organic evolution, using all the tools available to us in the present day, from YouTube to the concert hall.” (“Behind the Cello” 2014)

Not everyone has been eager to jump on the “we are the world” bandwagon, however. For decades numerous critical voices have raised concerns about globalization’s dire effects: on one hand that it further marginalizes rural and minority forms of expression, sometimes pushing them to the point of extinction, and on the other hand privileging commercially dominant mass-mediated ones. Ma’s optimistic view firmly stresses globalization’s positive rewards however, summarized by his statement, “globalization creates culture.”

His SRE musical journeys have only reinforced this conviction. Interactions brought about by globalization “don’t just destroy culture; they can create new culture and invigorate and spread traditions that have existed for ages precisely because of the ‘edge effect,’” notes Ma in “Behind the Cello.” “Sometimes the most interesting things happen at the edge. The intersections there can reveal unexpected connections. Culture is a fabric composed of gifts from every corner of the world.”

As a leading cello soloist, it’s almost predictable that Ma would cite the story of one of the movements in J.S. Bach’s Cello Suites, at the core of cello repertoire, to support his main thesis. He tells us it’s one of his favourite stories.

“At the heart of each suite is a dance movement called the sarabande. The dance and its music originated among the North African Berbers, where it was a slow, sensual dance. It next appeared in Spain where it was banned because it was considered lewd and lascivious. Spaniards brought it to the Americas, but it also traveled on to France, where it became a courtly dance. In the 1720s, Bach incorporated the sarabande as a movement in his Cello Suites. Today, I play Bach [as] a Paris-born American musician of Chinese parentage. So who really owns the sarabande? Each culture has adopted the music, investing it with specific meaning, but each culture must share ownership: it belongs to us all.” (“Behind the Cello” 2014)

Ma’s tracing of the sarabande’s musical (but also choreographic) journey, a string of exchanges and evolutions, bring to light at least six geo-cultural regional affiliations: North African, Spanish, American, French, German and Chinese. Ma’s statement, moreover, forcefully promotes inclusiveness and multiple authenticities while challenging normative monocultural ownership models and also by implication, notions of simple cultural authenticity and “purity.” In his statement Ma proposes an equitable extension of ownership of cultural practices across several regions, rather than to sole actors, further suggesting its ultimate and most appropriate resting place is universal (“ownership…belongs to us all”).

Ma also points out in “Behind the Cello” the importance of cultural “necessary edges,” liminal boundaries where intersections and exchanges often first take place, using another metaphor borrowed from another discipline. “The ‘edge effect’ in ecology occurs at the border where two ecosystems – for example the savannah and forest – meet. At that interface, where there is the least density and the greatest diversity of life forms, each living thing can draw from the core of the two ecosystems. That is where new life forms emerge.” Human society also requires such necessary edge sites, he argues. “The hard sciences are probing one far end of the bandwidth, searching for the origins of the universe or the secrets of the genome. People in the arts are probing the other far end of the bandwidth.” He concludes that only when “science and the arts, critical and empathetic reasoning, are linked to the mainstream will we find a sustainable balance in society.”

Is this the sort of liminal juncture, the “necessary edge” where the SRE also does its most creative, its most culturally valuable work?

Having a Toronto street named after him – Yo-Yo Ma Lane runs across from the Music Garden he helped design – certainly gives a living musician street cred in this too often cold burg. And there is evidence that the SRE’s secular universalist musical philosophy may have a particular resonance with Toronto audiences’ musical values and expectations. Chris Lorway, director of programming and marketing for Massey Hall/Roy Thomson agrees. In an August 18 e-mail he wrote that SRE’s guiding principles and mandate to promote “collaboration and cultural exchange, performing music that links to the past, yet reflects our 21st-century global society, align seamlessly with our evolving music city.” It’s a view that meshes well with Toronto’s public and political persona as “one of the most diverse cities in the world.”

Bassist Jeffrey Beecher: inside the SRE. Jeffrey Beecher is principal bassist with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and serves on the faculties of the Glenn Gould School of the Royal Conservatory of Music and the University of Toronto. He also makes time to tour the world with the SRE and to perform with international orchestras. On August 13 the affable Beecher took a break from an orchestral gig in upper New York State to speak to me on Skype. I was curious about how and when he was invited to play with the SRE.

“It was my sixth-degree-of-separation connection to some of the string players in the group that got me an invitation in 2004 to play with the SRE and then to tour with them.” It proved a satisfyingly collegial experience. “It certainly wasn’t an ordinary orchestral audition,” he mused “and I’ve been playing with them ever since!”

I explored with Beecher the constellation of ideas which gave birth to the SRE, primarily couched in this article so far in the words of its founder Yo-Yo Ma. Ma’s celebrity draw is such that even today, 15 years into the ensemble’s successful career, his name often precedes appearances of the SRE on concert marquees. Interestingly, Beecher portrays a more complex internal dynamic that has evolved within the group. “Over the years the group has experimented with several leadership models. Though he is the artistic director, Yo-Yo Ma believes in flattened hierarchies.”

It’s a sharing and supportive approach that applies to acquiring and adapting the bespoke repertoire for SRE’s multi-ethnic non-standard instrumentation as well. “It’s really on all of our shoulders. We players are as much witnesses to the creative process as recreators [in the usual classical music sense] in rehearsal and on stage. I’d say that every member of the ensemble has an opportunity to creatively contribute. I’m working on an arrangement [for SRE] right now.”

For Beecher the combination of the different perspectives brought by musicians from diverse backgrounds culminates in real-time performances on stage. “Because we’re coming from so many musical backgrounds, such as represented by the [Galician] gaita, [South Asian] tabla, [Chinese] pipa and [Iranian] kamancheh, one key question for me regarding the evolution of our group is: in what directions do the musicians collectively want to take their music in 2015?”

How does the SRE maintain such a unified, collective focus, I asked. “One of Yo-Yo Ma’s gifts is keeping many people and ideas in his mind at the same time,” he replied. “His attention, and the group’s, is not centrally located in one particular ethnic community, but rather it’s always mobile. I like to think of our model of music making as a caravanserai resting for one night and then moving on.” There’s that silk road metaphor again.

As for the educational component of SRE’s work, the parent Silkroad organization has been affiliated with Harvard University since 2005, encouraging “dialogue among artists and musicians, educators and entrepreneurs, through mentorships and workshops,” as its website declares. This chimes with Ma’s objective of attaining a sustainable educational balance where science and the arts, critical and empathetic reasoning – qualities too often unbalanced in mainstream society – are linked in symbiotic harmony.

SRE continues that mission during its September 2015 Toronto residency – not that it hasn’t held workshops in the city before. Beecher reports that “last year we led a series of rewarding workshops with Regent Park School of Music students during the inauguration of the Aga Khan Museum.” Over the years the Aga Khan Trust for Culture has been an enthusiastic SRE supporter. For example, not only is it a partnering presenter of the SRE’s September 15 Massey Hall concert, but it is also hosting a music workshop at the Museum, inviting students from Massey Hall and Roy Thomson Hall’s Share the Music program. These lucky learners will participate in a special educational program at the Aga Khan Museum with the Ensemble the week of the performance.

Yo Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble has grown well beyond the model of a gigging musical ensemble, the breadth and scope of its vision eloquently articulated by its high profile cellist leader and gifted musicians. Already enjoying success today, the SRE is well positioned to continue to influence the course of future musical streams, an ambition only a very select few other musical groups have considered putting on their bucket lists.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.