As a flutist, composer, conductor, and teacher Robert Aitken has had an impact on musical life in Canada that is hard to over-estimate. But his highest profile locally is with New Music Concerts, which he founded in 1971 with composer Norma Beecroft. As its long-time artistic director, he has put Toronto on the map as an international centre for contemporary music. He has attracted the top composers in the world here –like Iannis Xenakis, Witold Lutoslawski, Pierre Boulez, György Ligeti, John Cage, Elliott Carter, Toru Takemitsu, Helmut Lachenmann and Mauricio Kagel. As well, he has premiered many pieces by Canadian and international composers. His own compositions have all been published and recorded. As a conductor in Canada he leads the New Music Concerts ensemble, and has been involved in a great variety of performances including the turbulent Canadian Opera Company production of R. Murray Schafer’s Patria I in 1987.

As a flutist, composer, conductor, and teacher Robert Aitken has had an impact on musical life in Canada that is hard to over-estimate. But his highest profile locally is with New Music Concerts, which he founded in 1971 with composer Norma Beecroft. As its long-time artistic director, he has put Toronto on the map as an international centre for contemporary music. He has attracted the top composers in the world here –like Iannis Xenakis, Witold Lutoslawski, Pierre Boulez, György Ligeti, John Cage, Elliott Carter, Toru Takemitsu, Helmut Lachenmann and Mauricio Kagel. As well, he has premiered many pieces by Canadian and international composers. His own compositions have all been published and recorded. As a conductor in Canada he leads the New Music Concerts ensemble, and has been involved in a great variety of performances including the turbulent Canadian Opera Company production of R. Murray Schafer’s Patria I in 1987.

Yet ironically, outside Canada, Aitken is known more for his virtuosic flute-playing in a broad range of repertoire from the baroque, classical and romantic eras than for his work in contemporary music. As well, his conducting and teaching take him throughout the world. In fact, for sixteen years, up until 2004, he was professor of flute at the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg, Germany. His technique of flute-playing has even been the subject of a Ph.D. thesis, “A Description and Application of Robert Aitken’s Concept of the Physical Flute,” by Robert Billington.

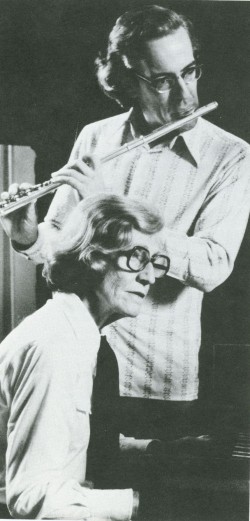

Born in 1939 in Nova Scotia, Aitken counts as his main teachers Nicholas Fiore in Toronto and Marcel Moyse at Marlboro, and then in France. For many years Aitken played in the Lyric Arts Trio with his wife, pianist Marion Ross, and soprano Mary Morrison. He also teamed up with pianists like Glenn Gould and William Aide, harpist Erica Goodman and harpsichordist Greta Kraus. Aitken joined the Toronto Symphony in 1965 but left five years later to pursue his solo career. It was the next year that he started New Music Concerts.

I met with him at the office of New Music Concerts in downtown Toronto. Before I even had a chance to ask him a question, he jumped in to voice his frustration over having so many things to get done before he heads off to Europe to give concerts and sit on a competition jury.

Aitken: There’s so little time to do everything. That was always the story of my life, and it hasn’t changed now that I’m older. I love everything that I’m doing – there’s almost nothing that I do that I don’t like. But there’s not enough time to enjoy it, and sometimes not enough time to do it to my total satisfaction.

Margles: Is it difficult to find the time to compose?

I’ve been trying for a couple of years now to finish a piece for the American Flute Association. The phone keeps ringing, or personal things come up. You can’t just shove them away in order to compose, because our families are a big part of our lives.

I’m also trying to finish a chapter I’m writing on John Weinzweig, who was my composition teacher at the University of Toronto. It’s for a book that John Beckwith and Brian Cherney are editing on his music. He was a great orchestration teacher. When you look at his music, it looks almost naïve, and it’s never virtuosic. But you can get into real trouble performing it. So I’m calling my chapter, “How To Play Weinzweig”.

On top of everything else you’re involved in, you do the pre-concert interviews with guest composers and players before performances at New Music Concerts. Do you enjoy doing those?

I’m always very nervous about those talks - more nervous about the talks than the concerts. So I’m in a bad mood most of the afternoon before the concerts just worrying about them. I’m always trying to get someone else to do them. But people say they really like them because I ask questions that are sometimes surprising.

You ask questions that I want to hear the answers to.

I try to ask questions that I want to have the answers to!

Have they ever been published?

Unfortunately most of them were not recorded. But we did just produce a video of a pre-concert talk I did with Elliott Carter, along with a recording of our most recent concert of his music. He has his 100th birthday in December.

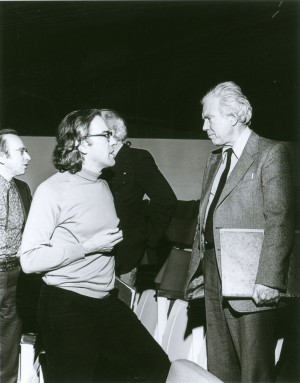

Interviewing Elliot Carter

Interviewing Elliot Carter

And he’s still writing. You’ve had such a long relationship with him – do you find his music has changed?

It’s warmer and more affectionate.

Yet he hasn’t compromised his style. Are you surprised that such a supposedly difficult composer has achieved so much success?

Now – but before, people stayed far away from playing his music. That changed when he started to write single-voiced pieces in the early 1990’s.

He wrote his first solo piece, Scrivo in Vento for me in 1991. Many of us had been asking him for a long time to write a solo piece for them. But because he only wrote contrapuntal music, he didn’t want to. I was living in Freiberg, and he had come to Basel, which is close by, to bring some music to the Sachar Institute, where they keep all his manuscripts. When we went out for supper, I said he should write a fifth movement for Bach’s Sonata for Flute Solo because it ends with the bourrée, and Bach never ended with a bourrée. He listened – he’s a very good listener, and he remembers everything. About three weeks later, he phoned me and said that the piece was almost done, but he just had a few questions. I said, “You’re kidding!” Now he writes solo pieces without end.

Carter, Boulez, Xenakis, Lutoslawski – you’ve given Toronto audiences a chance to hear the most important composers of our time. Do you find that the composers ever get influenced by their experiences here with New Music Concerts?

For a lot of people we’ve brought, it was their first time in North America. When oboist Heinz Holliger made his first trip here, we had Carter on the program with him. Heinz is very outspoken. He said, “Why are you doing Elliott Carter? That old fogey – his music’s not interesting.” But then, after doing that program, he became a great lover of Carter’s music, one of Carter’s biggest supporters. He phones him probably every week. That’s amazing, because he had been totally against Carter until then.

Holliger’s career strikes me as being similar to yours because, as well as performing contemporary music and composing, he played the whole range of repertoire including baroque.

I just wish that I would get concerts playing traditional music in Toronto today. I seem to be labelled a contemporary music specialist here. Before, especially when harpsichordist Greta Kraus was alive, I played equal amounts of traditional and contemporary music. Greta and I played together every Thursday afternoon for maybe ten years. We did a concert series called Flute Through the Ages at the St. Lawrence Centre that would sell out in a day. In other countries I frequently perform and conduct concerts of traditional repertoire. I recently took the Wiener Konzertverein, which is a chamber orchestra out of the Vienna Symphony, on a ten concert tour. The repertoire was not contemporary at all – I played a C.P.E. Bach concerto, and conducted Grieg’s Holberg Suite.

Is it tricky for a modern flute-player to perform baroque music today, with so many period instrument players specializing in baroque music?

Is it tricky for a modern flute-player to perform baroque music today, with so many period instrument players specializing in baroque music?

People don’t seem to want to listen to baroque music played on modern instruments. At the moment I don’t know any flutists that are playing both contemporary and baroque. Most of us are too inhibited now to play baroque music on our modern instruments.

Is it because of the style of playing?

Greta had a style of playing like Wanda Landowska – she used the same kind of harpsichord. In a way it was very romantic, but it was fabulous to listen to. The balance was always excellent. Plus, we played with a natural rubato nobody plays with today. I suppose they don’t want to, but I’m not sure if anybody can.

If Greta were still alive I would do a baroque concert in Toronto, I bet you it would come under super, super criticism – but I also bet that people would like it.

Do you have problems with period performance styles today?

Oh, lots of problems. Especially when string players crescendo and decrescendo on every note, and then the flute players copy. They say that’s the way people played in that time. But how do they know for sure? And even if the strings did do that swell, why would the winds do it – just because the strings did it? Anyways, I’m sure that the best string players did everything in their power to not do that. The mere fact that it happens by drawing a baroque bow across a string doesn’t mean that they actually played like that. And there are wonderful baroque flute players like Barthold Kuijken and Conrad Hunteler who don’t do that.

Before period instruments, were modern flute players paying much attention to authenticity in baroque music?

Jean-Pierre Rampal, I think, did. I went to him to study French baroque. He was fabulous at Couperin, Rameau, Blavet and all the French baroque composers

Would his style of playing be appreciated by period performers today?

Not with the authentic period-instrument people – not a hope!

Why?

Because he played in a natural musical way. But today, people still love his old recordings. They have lots of improvised ornaments which relate well to period playing, except that he kept sticking in diatonic runs all the time. We know that wasn’t done, because we have lots of other examples where composers wrote out the ornamentation that they wanted. But when it came to trills and ornaments of that type, no one could beat him, then. Nobody today, either – he was fabulous.

How do you choose pieces to program for New Music Concerts?

We try to show what is most interesting among the current directions in contemporary music. From the very beginning the series did not just reflect my taste or Norma’s. So when we did Grand Pianola Music of John Adams, it wasn’t my direction in music, but we picked one of his greatest pieces, and it really spoke for him. The same with Steve Reich – when he began to write phasing music, I thought “Come on – show that to children, but not to us.” I was totally against him for a long time. But after Russell Hartenberger and Bob Becker, who were anchors in Reich’s own ensemble, moved to Toronto, they kept pressuring me to do his music. I realized we had to because he was becoming so famous.

I had a really big fight with Reich on the phone, because he did not want to have anyone except his own group performing his music. I said, “We have very good musicians in Toronto. We will learn the music perfectly. We have all the instruments – everything you need.”

He said, “But they’ll never be able to learn this music – it’s so difficult.”

So I said, “If you don’t let us play this music, what’s going to happen when you die? Nobody is going to know how to play your music. Don’t you think it’s time that someone plays it besides just your own ensemble?” So finally he agreed. Our concert was the first time any ensemble played Steve Reich’s music that was not his own group. Of course, we were very well coached, having Russell and Bob involved, and Steve himself came for at least a week. After that concert, I had a different appreciation of his music. I still think the phasing is just too obvious. But Drumming, I think, is a great piece, and it does employ phasing.

How do you judge today’s music?

I prefer pieces that are provoking and challenging. But I have a lot of difficulty today judging what is a good piece and what is not a good piece. It may be easier to say what is an effective piece and what is not an effective piece.

I remember when we did John Cage’s Roaratorio in Convocation Hall with Cage reading James Joyce, and loudspeakers all over the place. The first night we had 1,300 people – imagine, for a contemporary music concert! The next night there was a terrible snowstorm and still 800 people came. John Beckwith showed up on his cross-country skis. That was 1982. In those years we had lots of pieces that were really on the edge. We could afford to take chances. Today, whenever we want to do something controversial, we always have to worry about whether we can get the money.

Are composers themselves taking fewer chances today?

Absolutely — I think the computer did that. Computers kill the imagination in music. When you compose with a computer, it’s too much trouble to do something like complicated rhythms or really wide intervals. Unfortunately, there’s now a whole generation that has been trained by using a computer. Any time I’m on a jury for an international composition contest, we can always tell which pieces were composed on the computer.

But it’s harder for composers today because they have to make their own rules. There are people taking chances, but the funny thing is, the chances they are taking are the same ones that were being taken in the 60’s and 70’s, because it’s all cyclic. Often when I look at those pieces by composers who think they are doing something really risky, all I see is something that was done before.

Right from the beginning of New Music Concerts you set the mark high, presenting Italian composer Luciano Berio in your very first year.

That was actually our first concert. Before that concert, we put little ads in the newspaper that just said, “Berio is coming.”

Do you think Toronto is good for new music?

It really is. There are a lot of groups now, not just us, so I do wish that our councils would recognize our value. We had a couple of years where they cut us down, seriously reduced our grants - not the Toronto Arts Council but the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council. Now we are creeping up again, but we are still not up to the level that we were at in 1982.

Are there many organizations in the world devoted to contemporary music like yours?

There are actually lots in Europe, but they have salaried players. The musicians play only contemporary music all the time.

Does that affect the way they play?

I think the music comes out better with musicians who play a mixture of repertoire. With New Music Concerts, I cannot think of any occasion where a composer who came here didn’t say we had given the best performances he had ever had of his pieces. If musicians play only contemporary music there is a risk that they just do what’s on the page, and forget about doing something with the music. But our musicians are so accomplished in all repertoire that they bring interpretive abilities to contemporary music. It’s not only with New Music Concerts – it’s like that all over Toronto.

It’s also because we try to rehearse enough, which doesn’t just mean getting the notes right and in tune. It’s to be familiar enough with the piece that when you are playing your line, you know what’s going on somewhere else. If you can hear the counterpoint or some chords that are against you, then you play differently.

You usually manage to bring the composer here – is that important?

From the first day our intention was to always have the composers here. Without the composer, you don’t have a hope in hell of knowing that what you’re doing is correct. The players play with more enthusiasm, because they want to please him. And when they have questions, they can get the answer right away. When it is possible to speak to the composer, that’s the best situation of all.

Does being a composer have an effect on your approach to playing?

I use a lot of analysis when I’m playing. Marcel Moyse, the flute teacher who had the biggest influence on me by far, taught us analysis. He made us aware of how a piece was composed so that we had a better idea of how to play it. Like any language, if you don’t understand the musical language of the composer, you can’t understand what’s being said. And if the performer doesn’t understand the language there is no hope of the audience understanding the piece being performed.

Does the fact that you write music influence your teaching?

When I teach flutists, basically, I teach them how to analyze the piece. All a teacher can teach you at any time is how to listen and how to teach yourself – those are the most important things you can teach anybody.

Have your compositions changed much over the years?

Even the titles I’m using show a change in my attitude towards composition. The piece I’m working on now is called Remembrances, and I’m calling the first movement Tsunami. The whole piece will certainly be more accessible than any of the other pieces I have written.

In what sense?

In the sense that I’m not choosing an obscure title and writing an obscure piece around it. Each of my pieces is quite different, although I like to think that all my music takes the listener to a world they didn’t know, someplace that they’ve never been before. Otherwise, why write the piece? But when I began to compose, I wanted to write pure music. Then I went around the world – Japan, Hong Kong, Sri Lanka (which was Ceylon at the time), India, and Turkey. When I got home, I had so many musical experiences in my head that I needed to get them out. I had always been outspokenly against composers writing music influenced by other cultures, unless they were from those cultures. But after that trip I had to do it.

I wrote Remembrances for a flute orchestra of twenty-six flutes –piccolos, C flutes, alto, bass and contrabass flutes. If I had decided to write for flute quartet, with just four parts, it would have been finished already. But I’m writing 26 parts.

Are these titles descriptive?

Tsunami is fairly literal at the beginning because a flute orchestra is fabulous for doing virtuosic things like cascades. The second movement, Solemnes, recalls the monastery in France which was assigned the job of researching and reestablishing the old Gregorian chant for the Roman Catholic Church. I learned about that from my University of Toronto days, when I studied paleography with Harvey Olnick. The first time I went to a church service at Solemnes it was beautiful beyond belief. Everything was sung. It was a total experience, with incense and so much atmosphere. That experience is still very big in my mind. Solemnes opens up like a cloud from a torrent of piccolos and low bass flutes to unison Gregorian. When you have that many flutes playing unison, they create a sound you will never forget.

What’s slowing me up is the last movement, which I want to call Caracas. It’s inspired by unbelievable Venezuelan flute-players like Huáscar Barradas. I think the greatest Latin flute playing by far is in Venezuela. It’s tricky because I don’t want to copy the style literally.

If you had to choose one aspect of music-making to concentrate on, what would that be?

Practising the flute.

Do you mean performing?

Yes. I think as we get older, our ears become more acute, and we are much more critical. To be a good player, you have to be critical of yourself, so I am very critical. As I criticize myself, I think my playing gets better. I think I’m actually doing it better than ever before.

RECORDINGS and COMPOSITIONS

A list of Robert Aitken’s many recordings is available on his website at www.bobaitken.ca, as is a list of his compositions.