How do you celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of a composer?

The obvious answer is with a concert, or even two, both of them freebies. And why not commission a new work in his name while you’re at it? You can also mount a symposium of scholarly papers, create a website in his name to perpetuate his legacy, and even have the historical society put a commemorative plaque on the building where he grew up.

The obvious answer is with a concert, or even two, both of them freebies. And why not commission a new work in his name while you’re at it? You can also mount a symposium of scholarly papers, create a website in his name to perpetuate his legacy, and even have the historical society put a commemorative plaque on the building where he grew up.

John Weinzweig (1913–2006), the recipient of these tributes, is not just any composer. There are three words that everyone who knew him uses to describe the Weinzweig legacy: composer, teacher and activist. These are not separate threads. Rather, they are woven together into a single tapestry. The man and his music in all its guises are inseparable.

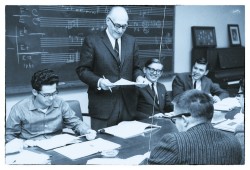

He was a force of nature. In terms of composition, Weinzweig was a true pioneer, a voyageur of art who introduced 12-tone serialism to Canada, and with it, the aesthetic of New Music. As a teacher, first at the Royal Conservatory, then at the University of Toronto (1939–77), he is the acknowledged doyen of Canadian concert composers whose legion of devoted former students literally spans the country from sea to sea.

How’s this for an impressive line-up of men and women of music who passed through Weinzweig’s influential hands? Harry Somers, Harry Freedman, Murray Adaskin, Phil Nimmons, Victor Feldbrill, Howard Cable, R. Murray Schafer, Norma Beecroft, John Beckwith, Milton Barnes, Srul Irving Glick, Brian Cherney, Robert Aitken, David Jaeger and Marjan Mozetich, to name but a few.

How’s this for an impressive line-up of men and women of music who passed through Weinzweig’s influential hands? Harry Somers, Harry Freedman, Murray Adaskin, Phil Nimmons, Victor Feldbrill, Howard Cable, R. Murray Schafer, Norma Beecroft, John Beckwith, Milton Barnes, Srul Irving Glick, Brian Cherney, Robert Aitken, David Jaeger and Marjan Mozetich, to name but a few.

As an activist, Weinzweig is credited with establishing the art of composing as a full-time profession in Canada. Not only that, he was also a major player in founding the infrastructure that supports the professional composer — the Canadian League of Composers which is the advocacy group, the Canadian Music Centre which is the library to house their scores and SOCAN (Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada), to protect royalty rights.

As Weinzweig himself said: “You can’t separate the politics from the art.” Part and parcel with his composing was his relentless pursuit to get the works of contemporary composers performed. (And conductor Victor Feldbrill, a longtime Weinzweig friend, adds: “Even those composers he didn’t like.”). In fact, Weinzweig was known for firing off thoughtful if hectoring letters (written on a mechanical typewriter) to CBC bigwigs and other cultural criminals whom he felt were betraying the cause of New Music.

As Weinzweig himself said: “You can’t separate the politics from the art.” Part and parcel with his composing was his relentless pursuit to get the works of contemporary composers performed. (And conductor Victor Feldbrill, a longtime Weinzweig friend, adds: “Even those composers he didn’t like.”). In fact, Weinzweig was known for firing off thoughtful if hectoring letters (written on a mechanical typewriter) to CBC bigwigs and other cultural criminals whom he felt were betraying the cause of New Music.

In Larry Weinstein’s Gemini Award-winning, 1990 documentary film, The Radical Romantic: John Weinzweig, the composer succinctly states the reasons for his activism. Declares Weinzweig: “I take action. I criticize publicly. I can’t bear to watch programming people having no regard for artists ... composers die from frustration, not starvation.”

Thus, one would think, given the importance of Weinzweig in the Canadian cultural firmament, that this centenary celebration would be a big gun affair. Not so. With a budget of just over $100,000, the celebration is on a very modest scale. For example, the Weinzweig concerts are taking place at the University of Toronto’s 490-seat Walter Hall. What’s more, the flashpoint for this public tribute came from a private place — the composer’s son Daniel.

“We’re facing new music amnesia in this country,” says Daniel. “We idolize authors and pop artists, but not our concert composers. Two New Hours is gone from the CBC and so are the guts of Radio Two. We celebrate Mozart’s birthday, but not our own masters. I’m my father’s son. I’m a fighter. I feel passionately about the cause which is to promote my father’s music. I have taken up the responsibility. If I don’t do it, who will?”

“We’re facing new music amnesia in this country,” says Daniel. “We idolize authors and pop artists, but not our concert composers. Two New Hours is gone from the CBC and so are the guts of Radio Two. We celebrate Mozart’s birthday, but not our own masters. I’m my father’s son. I’m a fighter. I feel passionately about the cause which is to promote my father’s music. I have taken up the responsibility. If I don’t do it, who will?”

Eighteen months ago, Daniel sprang into action by creating a 22-member advisory board, primarily because neither Daniel nor his brother Paul is in the music field. Daniel is a managing partner of Searchlight Recruitment, a head-hunter group for cultural institutions. Paul is a retired sociology professor. The advisory board, with Daniel as chair and Paul as a member, was configured to make up for the brothers’ lack of expertise by bringing together academics, composers, arts administrators, government and private sector cultural czars, and music professionals.

The centrepieces of the centenary are, of course, the two concerts devoted to Weinzweig’s music, so it behooves this writer to give a sense of Weinzweig the composer.

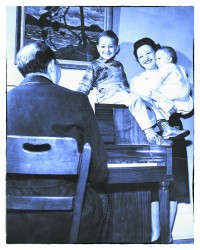

First of all, Weinzweig came from a musical family. His father Joseph was a musician wannabe who became a furrier after immigrating from Poland. And then there was his father’s baby brother, Morris “Mo” Weinzweig, a Groucho Marx lookalike, and an acclaimed Toronto saxophone player. There were also four cousins who were musicians. Weinzweig studied piano, mandolin, tenor saxophone, tuba, double bass and harmony. He both played in and conducted the Harbord Collegiate orchestra. During his high school years, he and “uncle Mo” played at weddings, bar mitzvahs, political rallies and lodge meetings. As Weinzweig has famously said, at 19 he decided to take music seriously and become a composer.

At the core of Weinzweig’s music is modernism. When he was a student at U of T (1934–37), he suffered through the classes of Healey Willan (counterpoint and fugue), Leo Smith (harmony) and Sir Ernest MacMillan (orchestration) because he felt constrained by their British conservative tradition of producing clones of Bach to Brahms. In fact, an early Weinzweig work such as The Enchanted Hill (1938), inspired by a poem by Walter de la Mare, was a quintessential example of late romantic influences. “Composition was not taught,” he scoffs in the Weinstein film, hindsight being 20/20.

At the core of Weinzweig’s music is modernism. When he was a student at U of T (1934–37), he suffered through the classes of Healey Willan (counterpoint and fugue), Leo Smith (harmony) and Sir Ernest MacMillan (orchestration) because he felt constrained by their British conservative tradition of producing clones of Bach to Brahms. In fact, an early Weinzweig work such as The Enchanted Hill (1938), inspired by a poem by Walter de la Mare, was a quintessential example of late romantic influences. “Composition was not taught,” he scoffs in the Weinstein film, hindsight being 20/20.

When Weinzweig was doing his Master’s at the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester, he was introduced to composers of the 20th century such as Stravinsky. The school, however, did not teach 12-tone. In fact, an Eastman professor referred to Schoenberg as “that perverted Jew.” Weinzweig discovered 12-tone on his own by reading au courant music journals and analyzing Alban Berg’s Lyrische Suite from a recording. When Weinzweig brought 12-tone serialism to Canada, in one fell swoop, he overthrew 19th century romanticism, revolutionized the teaching of composition, and opened new doors for his own creativity.

In the Weinstein film, the composer claims that he wrote moods and feelings, or an absence of style. “I’m a musical adventurer ... I’m influenced by everything and everybody,” he declares. Feldbrill talks about Weinzweig’s experiments with bending tones and playing with pizzicato and glissando, and the fact that as he got older, his works got smaller and more complex. In his later repertoire, he was influenced by the blues.

Says Feldbrill: “Even in John’s large scale pieces, there is great clarity. The sound never seems cluttered. He also explored the possibilities of an instrument to its further limits by consulting with the players to really get a sense of what an instrument could be pushed to do. He was not a minimalist. Rather, he wrote in small portions, an expert in miniatures. He was also a master orchestrator.”

Electronic composer David Jaeger was senior producer for CBC Radio Music. When he inaugurated Two New Hours, the first piece he commissioned was Weinzweig’s song cycle Private Collection for Soprano and Piano, with text by the composer (1975). Or to be more precise, Weinzweig commissioned himself by coming to Jaeger with a proposal to write something for the sparkling personality of soprano Mary Lou Fallis.

“It’s a little known fact,” says Jaeger, “but John saw himself as primarily a vocal composer and a humourist. Just look at the hilarious song “Hello Rico?” (from Private Collection) which depicts a teenager’s phone conversation. He put his observations of life into his music. I’d say his signature is short stop modes of expression, those quirky little motifs that are unique to him.”

Lawrence Cherney, artistic director of the new music series Soundstreams, contributes descriptive words such as austere, rhythmic, punchy, energetic, concise and succinct to describe Weinzweig. Adds Cherney: “John’s work was not so much an evolution of styles, but a concentration of themes and interests. Things would catch his fancy and he’d pursue them till he found something else. In the mid 1980s, for example, his focus was choral music. He also liked to incorporate sounds from everyday life like popcorn popping. His texts became more colloquial than poetic.”

Cherney curated the Friday, March 8 concert. He and the advisory board were faced with a huge and eclectic array of works to choose from. “It’s the usual mixture for a tribute concert,” explains Cherney. “There are works well known, and not so well known. John’s composing career spanned 70 years, so we tried to choose from different periods and genres.”

The small stage at Walter Hall precluded any large symphonic work, so the program contains three chamber pieces with the 13-member string orchestra conducted by Feldbrill. Interlude in an Artist’s Life (1943) is an instrumental work with an ironic title. Weinzweig finished the score just before leaving his teaching job at the Royal Conservatory to join the Royal Canadian Air Force as a band instructor, composer and arranger.

Also included is the third movement of Divertimento No. 3 (1960) which features a solo bassoon. The piece is on the program because U of T student and bassoonist Bianca Chambul is something of a musical prodigy. Similarly, Refrains for Contrabass and Piano (1977) is a showcase for American James VanDemark, a professor at the Eastman School who is considered one of the world’s great virtuosos of the double bass. Three choral works will be performed by the University of Guelph Chamber Singers including the brilliant Hockey Night in Canada (1985) with its hilarious refrain, “Body check, body check, body check.” The other pieces are the more serious Prisoner of Conscience (1985), dedicated to Amnesty International, and Am Yisrael Chai! = Israel Lives (1952), an ode to the resilience of the Jewish people.

Acclaimed soloist Judy Loman will be playing excepts from 15 Pieces for Harp (1983). There is an amusing story connected with this work. Loman commissioned the score and after Weinzweig had written several pieces, he tried to get together with Loman, but she was always busy. As he explains in the Weinstein film, he couldn’t get the harp out of his mind and kept writing. When he got to 15 pieces, he called Loman, telling her that he felt like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, begging her to meet with him so he could stop composing. Weinzweig actually took harp lessons from Loman before he worked on the commission.

Weinzweig’s most famous chamber work is Divertimento No. 1 (1946) which features flutist Robert Aitken. And here’s a curiosity. Weinzweig was awarded the silver medal for Divertimento No. 1 at the 1948 London Olympiad (no gold medal was given out that year). As astonishing as it may seem, from 1912 to 1948, the Olympic Games included medals for architecture, literature, sculpture, painting and graphic art and music. The practice was abandoned after 1948 because the arts competitors were deemed “professional” and the Olympics was the domain of amateurs.

Aitken is also joining soprano Shannon Mercer and pianist Serouj Kradjian to perform Trialogue (1971). Weinzweig composed the work using his own very idiosyncratic texts. “It’s a perfect example of the humour that permeated John’s later works,” says Aitken. The flutist, in fact, delights in quoting some of Weinzweig’s eccentric lyrics. “It occurred to me that it never occurred to me.” “A sound has no leg to stand on.” “Your soul is showing.” “If it can be done, why do it?” “Hold on to your lives, here we go.”

The big deal is the new work, Dear John, for harp and soprano, by Andrew Staniland, performed by Loman and Mercer. Staniland was the 2007 recipient of the $3000 John Weinzweig Scholarship, awarded annually by U of T’s Faculty of Music to a graduating doctoral candidate in composition. He is currently an assistant professor of composition at Memorial University in St. John’s.

Says Staniland: “My two favourite Weinzweig works are 15 Pieces for Harp and the song cycle Private Collection, so it was natural to write something for harp and soprano. Because John wrote his own text for Private Collection, I decided to write my own lyrics, although I counsel my students not to do it because it’s hard to pull off. The work is a play on words: the Dear John rejection letter, the John Deere tractor and of course, an homage to Dear John Weinzweig. It’s whimsical, ironic and funny. It is also thoughtful, elegant and sincere.”

Robin Elliott, chair of Canadian music at U of T, organized both the symposium, which takes place on Saturday, March 9, and the noon hour concert on Weinzweig’s actual birthday, March 11. The latter features the Cecilia String Quartet, first prize winner at the prestigious Banff International String Quartet Competition in 2010. The program includes Sonata for Violin and Piano (1941), Sonata “Israel” for Cello and Piano (1949), both with pianist James Parker, and String Quartet No.3 (1962).

The violin sonata reflects Weinzweig’s new-found fascination with 12-tone. This composition also was a welcome break from grinding out neverending background music for radio programs for the CBC. The extended final cadenza for the violin reaches heights of virtuosity. The cello sonata, quoting an old Yemenite melody, is dedicated to the new state of Israel. While 12-tone in structure, Weinzweig loosens the serialism to allow expressions of joy and celebration. The elegiac quality of Quartet No. 3 reflects Weinzweig’s grief over the death of his beloved mother. It is widely considered to be among his finest works.

As for “Symposium: John Weinzweig, His Contemporaries and His Influence,” Elliott put out a call for papers and, as he quips, there was 100% acceptance. Eight proposals came in and eight comprise the symposium. “Half are lecture/demos,” says Elliott, “which means a lot of music. It’s not all talk.” The papers cover a wide range of topics including the string quartets, commissioning Weinzweig, the late piano works, a discourse on his 12 divertimenti, publishing a performing edition of Private Collection, and the Jewish-Canadian heritage of Weinzweig and Saskatchewan-based composer David Kaplan (b.1923). There is also a bit of nepotism. Diana Dumlavwalla is presenting a paper titled The Pedagogical Piano Works, and Elliott’s daughters, age 9 and 11, are playing these charming pieces.

In the final analysis, the mission of the John Weinzweig Centenary Project, as stated on the new website that Daniel set up (johnweinzweig.com), is not only to encourage performances of his father’s oeuvre, but to promote discussion about Weinzweig’s influence. The hope is that the specific focus on Weinzweig will, in turn, lead to greater audience awareness and demand for Canadian new music in general.

Even Daniel acknowledges that it is going to be a rough row to hoe. “CD sales are practically non-existent and music organizations are conservative in their programming,” he points out. “Contemporary composers can’t build up a reputation because their works don’t have a shelf life. The website will keep my father’s intellectual property alive. The future is the internet.”

And one final note. Weinzweig was a devotee of the legendary Harbord Bakery. It is, therefore, fitting that the bakery is catering the Monday night, March 11 reception at the Canadian Music Centre. (For a complete list of centenary events, visit johnweinzweig.com.)

Paula Citron is a Toronto-based arts journalist. Her areas of special interest are dance, theatre, opera and arts commentary.