“‘I shall take you to hear better music than that,’ the captain said; ‘we are just in time to hear the organ of St. Bavon. The church is open today.’ ‘What, the great Haarlem organ?’ asked Ben; ‘that will be a treat indeed. I have often read of it, with its tremendous pipes, and its Vox Humana that sounds like a giant singing.’”

— Hans Brinker or The Silver Skates, Mary Mapes Dodge

“The Vox Humana (Latin for ‘human voice’; also ‘voix humaine’ in French and ‘voce umana’ in Italian)” is a short-resonator reed stop on the pipe organ, so named because of its supposed resemblance to the human voice.”

— Wikipedia

This issue contains the tenth edition of The WholeNote’s annual choral Canary Pages, and also heralds Toronto’s seventh annual Organix festival. In a way the two things seem miles apart. Singing is the most natural form of music making, accessible to all, with no technological intervention. The pipe organ, at the other extreme, is so much of a man-made thing that individual pipe organs each have their own Opus number. And yet, perhaps, in the notion of the Vox Humana they are not so different after all.

The Vox Humana of the St. Bavon’s organ in Haarlem scared the living daylights out of the boys in The Silver Skates. “The storm [of the organ] broke forth again with redoubled fury. The boys looked at each other, but did not speak. It was growing serious. What was that? Who screamed that terrible, musical scream? Was it some monster shut up behind that carved brass frame? — some despairing monster begging for freedom? … At last an answer came — soft, tender, loving, like a mother’s song.”

Organist Dame Gillian Weir also has profound memories of St. Bavon’s. Weir, some of you will remember, gave the opening concert of the fourth Organix festival, May 1, 2009, on Casavant Organ Opus 3095, just arrived in its new home at Holy Trinity Church (from its original home at Deer Park United Church). She greeted the organ like an old friend (which it was) and the music they made together that night instilled a respect for the “King of Instruments” in even my profoundly anti-monarchist brain.

St. Bavon’s, Weir explained the following day, was the moment she knew what she wanted to do with her musical life: “I wanted to be a pianist, I loved the piano. But … when I was taken to Haarlem, in Holland … I spent three hours or so playing, till they said ‘You’ve got to go, the tourists are complaining,’ and I staggered off the organ saying ‘What happened? This is fantastic, this is music, this is wonderful.’ I became an organist on the spot.”

Weir is not part of the 11-concert Organix line-up this year. But for those of you who primarily have memories of organs badly played in situations where attendance was compulsory rather than elective, Organix might change your mind.

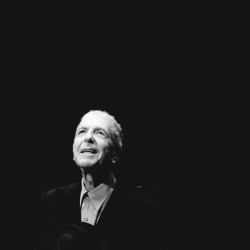

And speaking of distinctive human voices, May 14 will be the occasion of a pointedly non-classical gala concert at Massey Hall to celebrate the award of the ninth Glenn Gould Foundation Prize to Leonard Cohen. DISCoveries editor, David Olds, on page 60, catches up with some previous eminent winners. And, in the continuation of this little ramble, I find myself wondering what if Glenn himself …?

FITTING THE “LEN” IN GLENN:

FITTING THE “LEN” IN GLENN:

A SEMI-IMAGINARY ETHER-MAIL EXCHANGE between Brian Levine, executive director of the Glenn Gould Foundation, and Glenn Gould during which Levine breaks the news to Gould that there’s to be no classical component to the May 14 GGF Award Gala at Massey Hall.

GLENN: What the blazes do you mean you don’t want me at the gala? The powers that be are giving me a special 80th birthday pass just to be there. And I’ve been practising.

BRIAN: Hi Glenn, thanks for your kind note, and don’t worry, I appreciate your concerns. So let me answer as best I can. … First, as you can imagine, we’re thrilled that Leonard Cohen is the Ninth Laureate of The Glenn Gould Prize. I think that in many significant ways, he and you occupy very special and distinctive places in the Canadian cultural mythos. But our first consideration in mounting a gala is to pay tribute to our laureate in a way that is reflective of that artist’s special “voice” and contributions. We aren’t wedded to a single idiom, a particular mode of expression because philosophically, to take such a position would be to place an artificial constraint on art itself — the antithesis of the unbridled creativity that is at the core of what it means to make and communicate art.

GLENN: So?

BRIAN: So, in the case of Leonard Cohen, we have an artist whose work has its own “native voice” — his own performance — but which has spread out into the world in a wide range of styles carried by the poetic thread at the heart of all his work, in which artists of many backgrounds hear their own loves and longings, and infuse the music with their own styles.

GLENN: So?

BRIAN: So our goal was not to graft an artificial “classical” framework onto Cohen’s music but to build a gala performance which allowed some of this range of expressive idioms to find voice. The program is rich and varied.

GLENN: So?

BRIAN: So it would have seemed artificial to put a “classical” stamp on the program — and I’m sure that attempts to do so might have been a source of discomfort for Mr. Cohen himself.

GLENN: Ah, so. I would make Lennie uncomfortable, is that it?

BRIAN: In a larger sense, an artist like Leonard Cohen defies categorization. When it comes to the art of the song, I don’t find a ready distinction between the finest songs by major 19th century composers and 20th and 21st century composers, whether they identify as “classical” or “popular,” “simple” or “complex.” I have no doubt that in the 22nd century, Leonard Cohen’s music, whatever style it is performed in, will be regarded with the same love and appreciation that we accord to the major composers of lieder of the 19th century.

GLENN: Is that a “no,” Brian?

BRIAN: Our decision was to let Leonard Cohen’s songs speak to our audience in styles that seem most appropriate to him — just as our tribute to another great master, Oscar Peterson in 1993, was presented in his idiom, jazz. I hope this is somewhat helpful.

GLENN: Wait, how about if I promise to also use just three chords and hum the rest?

BRIAN: I’m happy to answer more questions if you would like to cover some additional points.

GLENN: Brian? … as regards that “three chord only” dig, I have to confess this is a bit more of a challenge than I thought. Does that “minor fall” count as an entirely separate chord? … Brian? Brian?

…

BRIAN: (to Len) You can come out now, he’s gone.

LEN: Hallelujah.

—David Perlman, publisher@thewholenote.com