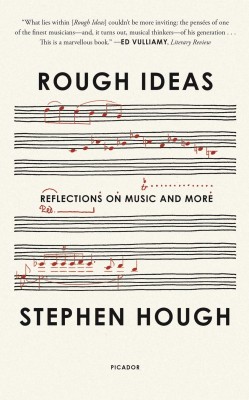

In Stephen Hough’s wonderful 2019 book Rough Ideas: Reflections on Music and More, the polymath pianist, writer, composer, religious scholar and music educator recalls an experience when he was confronted by the music of a pianist he did not recognize, performing the music of a composer he did not know. It turns out, when he inquired, that it was him at the keyboard, performing the music of Benjamin Britten, something that he had done countless times previously during his long and storied career. While this anecdote fits easily alongside the many other thoughtful and humorous stories that are peppered throughout the insightful book, it also highlights the issue of context and how what we hear—and how we hear it—changes depending on the environment.

In Stephen Hough’s wonderful 2019 book Rough Ideas: Reflections on Music and More, the polymath pianist, writer, composer, religious scholar and music educator recalls an experience when he was confronted by the music of a pianist he did not recognize, performing the music of a composer he did not know. It turns out, when he inquired, that it was him at the keyboard, performing the music of Benjamin Britten, something that he had done countless times previously during his long and storied career. While this anecdote fits easily alongside the many other thoughtful and humorous stories that are peppered throughout the insightful book, it also highlights the issue of context and how what we hear—and how we hear it—changes depending on the environment.

Over the last 18 months, the environment of “live” music has most certainly changed. From cheek-by-jowl seating in crowded concerts, to iPhone-captured solo performances recorded in kitchens and living rooms around the world and “Frankensteined” together as a “performance”, to Zoom broadcasts from empty concert halls, to, recently and thankfully, cautious re-openings at limited capacity with masked patrons seated six feet apart, is there really anyone left who fails to see how, as Hough articulated in our recent email exchange, “experiencing great music in the company of our friends and even strangers amplifies it in an extraordinary and irreplaceable way?”

Perhaps nowhere is this powerful union between art and humanity more apparent than in the concert hall where communities are found and formed during the collective experience of receiving sound waves manifested as beautiful music. On November 9, Hough will be in Toronto as part of this industry-wide re-opening: performing in-person as part of Music Toronto’s 2021/22 season at the Jane Mallett Theatre, Hough will play a concert of Chopin, Schumann, Alan Rawsthorne’s “Bagatelles” (a dedication to Hough’s piano teacher, Gordon Green), and Partita, a work of his own creation.

Hough’s insights into the complexities, responsibilities and privileges of life as a classical music performer are problematized and investigated in his book—reflecting Hough’s own complex lens as a writer, musician, composer, scholar, performer, fan, educator, deep religious thinker and openly gay man. To read Hough’s Rough Ideas is not to encounter a bifurcated narrative that dithers between multiple identities and perspectives, but rather is to immerse oneself in a decidedly human story that provides revelatory insight into the process of music-making (from ideation to performative realization) from one of the most gifted and prolific classical musicians alive today. Hough’s upcoming few months alone include, in addition to his own piano performances, a concert by the Takács Quartet featuring the string quartet Hough composed for the ensemble, performances of three of Hough’s song cycles, composing the test piece for next year’s Cliburn competition, completing a film score, and putting the finishing touches to a new book.

Thankfully there is nothing preachy or didactically instructive about either Hough’s writing or his music. In both, Hough skillfully transcends the political, tapping into something more universal in his desire to “bring joy, inspiration, and find common ground so we can all experience rapture and ecstasy together.”

It is the British-born 59-year-old’s underscoring of the egalitarian and democratizing power of music—despite his jet setting and global concertizing life—that I appreciated most about both my reading of Rough Ideas and our subsequent email exchange. “I’ve seen the joy in people’s faces as they return to the concert halls,” he remarked of his recent post-pandemic concertizing experiences. “A concert is a way for people to come together and experience something absolutely extraordinary in the company of other people…it’s what human beings are meant to do.”

It is the British-born 59-year-old’s underscoring of the egalitarian and democratizing power of music—despite his jet setting and global concertizing life—that I appreciated most about both my reading of Rough Ideas and our subsequent email exchange. “I’ve seen the joy in people’s faces as they return to the concert halls,” he remarked of his recent post-pandemic concertizing experiences. “A concert is a way for people to come together and experience something absolutely extraordinary in the company of other people…it’s what human beings are meant to do.”

Hough is equally thoughtful when creating a recital program for his concerts that balances new and under-performed compositions and composers with the sort of canonic fare that continues to inspire new possibilities for audiences and performers alike, such as the three Chopin pieces (Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47, Two Nocturnes and Scherzo No. 2 in B flat minor, Op.31) on offer at his upcoming Toronto concert.

I asked Hough how he manages to maintain his renowned inventiveness and effervescence when approaching music that he has, undoubtedly, heard, practiced and performed hundreds of times before. “I think the ability to do this is simply part of what it takes to be a concert pianist,” he responds. “I cannot help it when I sit down and play those familiar, wonderful Chopin works, or others in the core repertoire. They just charm, seduce, touch and thrill me every single time without my having to make any effort.”

With luck, Hough’s November 9 Toronto recital program will reflect all of this. It will also serve as a symbolic “bookending” of the pandemic in this city; his final concerts on the North American continent took place here (three performances of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 2 in C minor with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra) in February 2020, mere weeks before the initial lockdowns. It’s a return to Toronto that promises to touch and thrill—as well as to prove, as he himself wrote in our email exchange, that pandemic or not, art and humanity remain “indivisible.”

Stephen Hough performs Tuesday November 9, 2021 at Toronto’s Jane Mallett Theatre, presented by Music Toronto.

Andrew Scott lives in Toronto in a house amongst children, antiquated technology of yesteryear and many, many instruments. From this location, he makes music, writes letters, narrates radio dramas, composes poems, writes creatively, and submits journalistic and musicological pieces.