In a former Salvation Army building on lower Parliament Street in Toronto, a quiet revolution in music/dance/theatre creation is emerging at the hands of Citadel + Compagnie’s artistic director Laurence Lemieux and resident choreographer James Kudelka.

In a former Salvation Army building on lower Parliament Street in Toronto, a quiet revolution in music/dance/theatre creation is emerging at the hands of Citadel + Compagnie’s artistic director Laurence Lemieux and resident choreographer James Kudelka.

At the end of May and beginning of June, the company is remounting their Dora-nominated 2016 work Against Nature, based on the decadent 1884 novel of the same name (À Rebours) by Joris-Karl Huysman.

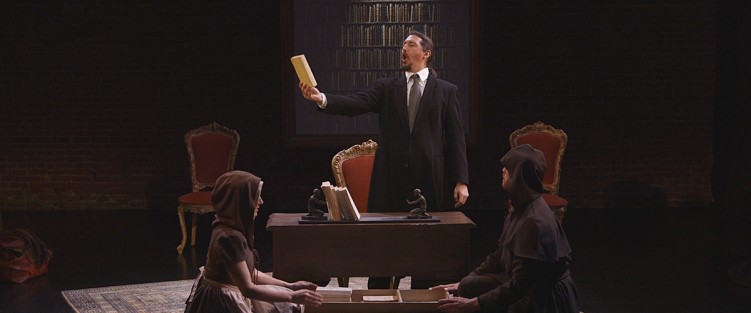

The central character of the story is Jean des Esseintes, a 19th-century aristocrat who has become so disgusted with human society in fin-de-siècle Paris that he exiles himself to a villa in the country to create for himself a perfect world of art and artifice. Against Nature is widely believed to be the novel that poisons the mind of Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s famous story The Picture of Dorian Gray, and in James Kudelka’s work we will also see the downward spiral of the hero, des Esseintes (played by baritone Alex Dobson), as he tries to escape nature and mortality with the help of his two servants (played by dancer Laurence Lemieux and baritone Koran Thomas-Smith).

What makes this work unique is its combination of opera, dance, theatre and visual art, and its creation for the specific salon-style performance space of the Citadel, which seats only 60 at a time. The creative team is a powerful mix of award-winning Canadian artists, including composer James Rolfe (The Overcoat, Beatrice Chancy), librettist Alex Poch Goldin (The Shadow), lighting designer Stephen Rossiter, and projection designer Jeremy Mimnagh. Accompanying the three performers onstage there will also be three musicians performing the score live: pianist Stephen Philcox, violinist Pamela Attariwala, and cellist Carina Reeves.

Leading the creative team as director and choreographer is James Kudelka, perhaps best known here as the artistic director of the National Ballet of Canada from 1996 to 2005, and the creator of many large-scale ballets including his own versions of Cinderella, Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, as well as many works for companies around the world, including audience favourite The Four Seasons.

Intrigued about the genesis of this project, its experimental nature and scale, I reached out to Kudelka to ask him about what had inspired him to make this change in focus from his earlier work.

The WholeNote: What drew you to this initiative, creating not only intimate salon-sized works, but works that cross genre lines to combine ballet/opera/theatre?

The WholeNote: What drew you to this initiative, creating not only intimate salon-sized works, but works that cross genre lines to combine ballet/opera/theatre?

James Kudelka: First, let me say that my preferred way to describe these works is music/dance/theatre. I don’t want anyone to think they are seeing a ballet or an opera, but I do want them to think they are seeing a theatrical event. We use singing and dancing, voice and movement—whatever will tell the story best. To call it opera will keep as many people away from it as calling it ballet would.

In brief, I was wanting to do something that used Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth but because of the nature of the story the possibility of it being a full-fledged opera house style ballet for the National Ballet of Canada was remote. There was too much in the novel that couldn’t be danced, mostly to do with debt and money. It went well beyond Balanchine’s saying that there are no mothers-in-law in ballet. This was an unmeetable challenge.

Because I was beginning to work at the Citadel I thought it was a good place to try an experiment, and use a librettist and a composer, and to make a rule that the women in the cast would dance and the singing men would carry the narrative challenges through text, and that the whole thing would be to music. Each of the art forms would be used to what it could do best. The remarkable thing is that though the men in the cast of From the House of Mirth carried the language, one never had the feeling that the women had no voice.

WN: Against Nature is the second part of a trilogy (of which the third part is still to come). Can you tell us about your choice of source materials and why they inspired you? I am intrigued by the contrast between Edith Wharton's The House of Mirth, the source of the first part of the trilogy, and Against Nature (À Rebours) by French-Dutch author Joris-Karl Huysman, the source material for the second part and current production.

JK: We had been working very hard to secure the rights to a different second project, that never came about. I went into my library and found Against Nature, which was a fascinating book I had read, but I really wondered if a music/dance/theatre adaptation was possible.

I met with the team—Alex Poch Goldin who had written the libretto for From the House of Mirth, and James Rolfe, a composer whom my agent suggested I meet—after the novel had been presented and read by them, and strangely I got excited enough by the idea of it that it lit a spark in us all. I don’t think any of the three of us went to that meeting with much faith in it until then. It was actually pretty grim.

From the House of Mirth had four female dancers, four male singers and five instrumentalists. For Against Nature I wanted to use a smaller ensemble, in the hopes that it would be less expensive to tour.

WN: Do you know yet what the source material of the third part of the trilogy will be, and how the three pieces will fit together?

JK: Yes, but there is no real connection between the pieces other than that they are all music/dance/theatre works. It is true that they are all late 19th or early 20th century sourced. I don’t have a thematic agenda, though I am the artist I am, and no doubt everything I do has some kind of connective theme because it has to come from a deep place within me to bother with it. As I get older I begin to wonder whether a whole career of creations is really just an exercise in trying to get the one idea you have right.

WN: How did the creative team for this project come together? Had you worked together before?

JK: I keep the librettist; I change composer from project to project. It happens that Alex Dobson (the baritone) and Laurence Lemieux have both been involved in both productions so far. It is not unusual for me to try and work with people I know, but I always try to work with someone I don’t know in each project to keep things stirred up and keep me out there and social, meeting artists from all disciplines and introducing new people to the team I know.

I prefer to work with Jim Searle and Chris Tyrell from Hoax for costume because we are a small organization and though we don’t have a permanent wardrobe department, having the same designers creates continuity from project to project and we can borrow from ourselves. They are also lovely and very flexible people…

WN: You are both choreographer and director of Against Nature. How do you incorporate directing actors and singers into your usual work as a choreographer of dancers? Have you found that your approach has changed between the first and second parts of the trilogy?

JK: I am not the music director of Against Nature, but in terms of basic moving the players around the stage, creating the situations and blocking and staging, motivations of character, props and overseeing all the elements, I am not doing anything differently than I would do or continue to do when I create a ballet for a ballet company. (When I rehearse something like The Nutcracker, my job is really almost solely direction, since the choreography was done before the show opened in 1995 and is still performed.) If there is something on a stage, it has been a choice made by a director, or a choreographer. The title ‘choreographer’ tends to lead one to think only of the dance. As artistic director of the National Ballet of Canada I was in charge of a large repertoire of narrative ballets that I myself did not create and these works do not direct themselves.

There is a confusion in this, because people have seen my two music/dance/theatre pieces and can’t really figure out how they came about. I think it would be more usual for a composer to want to write it before a theatrical production was planned. The truth is that in essence, I have an idea, and I invite a librettist and a composer, and after some discussion of tone and numbers and very basic restrictions (since creativity is best achieved with restrictions), I sit back and wait until everyone has finished their jobs and then I come in and finish the work by directing and choreographing. I basically start the fire and then I have to put it out.

We usually have a series of workshops on the way to the premiere. I think FHoM and AG both had two or three 2- to 3-day workshops which usually ended with a showing to interest patrons and start some conversations about how we are doing. It is then also a chance to invite costume and scenic designers in. We are able to work very holistically at the Citadel, creating the show as it evolves, lighting and projections coming into the space early and over a longer period. We bring lots of props and clothing from home. It is a very lovely process, very natural as the project takes shape. By the time we perform the finished project, it has not gone through the usual franticness of a move to a theatre and a broken projector and an unhelpful union crew. So often in our world the day of the opening is a nightmare and has little to do with the weeks of work it took to get to that day.

WN: Do you find that the intimate performing space changes how you approach directing and choreographing, and do you find that audiences relate differently to these hybrid works—particularly being in such close proximity to the performers?

JK: I do this work because of the intimacy, after so many years of trying to fill a stage in a 3200-seat hall. Not that I can’t do that, but it is exhausting. I think to put the audience itself in the actual room with the performers demands a heightened discipline from all concerned in that room. (If your cell phone goes off during the show you can’t hide in a 60-seat theatre!) To hear the breathing, and the inhalation before a word sung, the rustle of a silk gown six feet away, the sweat flying off a dancer, it just may be this kind of intimacy that is the future of theatre “in a world that’s at its end,” to quote the Master in Against Nature.

Against Nature plays at the Citadel May 22-25, and May 29-June 1 at the Citadel: Ross Centre for Dance, Toronto.