Coming back to Canada last month after two and a half weeks in Versailles, Paris, and London gave me rather severe culture shock for a while, but there were shows I knew I wanted to see before they closed in order to catch up with the Toronto music theatre scene – particularly because all three took a new look at classics for the stage.

Onegin by Veda Hille and Amiel Gladstone, presented by the Musical Stage Company at the Berkeley Street Theatre downstairs, June 4

Onegin began life as an epic poem by radical Russian writer Alexander Pushkin that, first published in serial form between 1825 and 1832, became a hit with the reading public. It also foreshadowed Pushkin’s own death, with the famous duel between the title character and his best friend Vladimir Lensky. In 1870, Tchaikovsky was asked to turn Onegin into an opera, which also became a huge success (and is still a reliable hit today). Tchaikovsky was also affected personally by the story: apparently not wanting to make the same mistake as Onegin, he divorced his wife and then married a young student who had written him a passionate love letter – another of the anchoring events of the original. So, from the beginning, Pushkin’s tale had a profound effect on all those who came in contact with it.

Onegin began life as an epic poem by radical Russian writer Alexander Pushkin that, first published in serial form between 1825 and 1832, became a hit with the reading public. It also foreshadowed Pushkin’s own death, with the famous duel between the title character and his best friend Vladimir Lensky. In 1870, Tchaikovsky was asked to turn Onegin into an opera, which also became a huge success (and is still a reliable hit today). Tchaikovsky was also affected personally by the story: apparently not wanting to make the same mistake as Onegin, he divorced his wife and then married a young student who had written him a passionate love letter – another of the anchoring events of the original. So, from the beginning, Pushkin’s tale had a profound effect on all those who came in contact with it.

At the start of the musical, presented by the Musical Stage Company at the Berkeley Street Theatre last month, all this history is mashed up into the opening numbers, performed by the cast as if they are a group of strolling players in a cafe inviting us, the audience, in to drink and take part in a rollicking romantic Russian tale – with audience participation. One character even tells us: “yes, it’s that kind of show.”

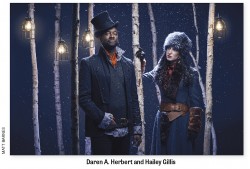

The first named character we meet is Lensky, a young poet who introduces us to the rest of the characters – finishing with his best friend Evgeny Onegin. It felt unusual to have Lensky so front-and-centre, yet Josh Epstein is so strong in the role that he rules the stage, bringing great energy to the scene. Onegin himself is described as a rake and a loner and yet very attractive; award-winning performer Daren A. Herbert inhabits the role with insouciant style, seemingly channeling Will Smith with a dash of Rex Harrington. The tongue-in-cheek travelling montage is hilarious and sets him up perfectly as the hero to be caught – and to be wary of.

When female lead Tatyana, played by Hailey Gillis, meets him, she falls in love immediately – and Gillis is so transparent in her emotions that she takes us with her every step of the way. In all versions of the story Tatyana’s ‘letter writing scene’, where she decides that in spite of all common sense she is going to write to Onegin to tell him that she loves him, is central. In the musical it becomes the heart of the story, in the form of Tatyana’s brilliantly performed, six-minute song “Let me die.” Gladstone and Hille’s stated goal of creating a song that “could be sung by a teenager today” was met completely, Tatyana even picking up and playing a guitar part way through, as any modern teenager in the throes of first love might do.

The tragedy begins with Onegin turning down Tatyana, telling her that “marriage is not for him, although if it were, she would be the one he would choose.” It gets worse when, out of pique, he flirts with her sister Olga, the fiancée of his best friend Lensky, leading in turn to Lensky challenging Onegin to a fatal duel.

Up to this point I was completely captivated by the story and performance and expected to have my heart thoroughly broken in the second half. Somehow, however, the final quarter of the show, where Onegin meets Tatyana again, did not have the effect on me that I expected. Looking back I think it may have been a result of the direction of the title character – or perhaps, missing material. In the ballet version of the story, Onegin has powerful melancholic solos that make achingly clear his sorrow and emptiness after Lensky’s death. While the musical gives Onegin moments to express this, there wasn’t ever a full song where we were given a personal connection with his pain.

What does almost work is the reprise and turnabout of “Let me die,” now sung by Onegin as he writes to Tatyana helplessly declaring his love for her while she, now married to another man, agonizingly turns him down. Gillis does a lovely job of showing us a Tatyana who has matured into an elegant woman with beauty and poise, who almost gives way to her reawakened love for Onegin – but again, there was something missing in the balance of the scene so that it felt more her story than his and not an equal tragedy.

Those caveats aside, this is a wonderfully energetic, young indie-rock version of Onegin that deserves a longer life. I left feeling a bit unsatisfied but still impressed and affected strongly enough by the show as a whole to buy the cast album on my way out. It will be interesting to see how this Onegin fares as it goes out in the world to other theatres, beginning with this production’s next stop at the 900-seat theatre of the National Arts Centre. It needs some tweaking in my opinion, but with that it should have a long life as the latest theatrical version of a beloved tragic story.

Porgy and Bess In Concert at Soulpepper, June 2

Again a tragic tale of love found and then lost, the glory of Porgy and Bess is the Gershwin score. Who has not heard some version of the lullaby “Summertime,” the biggest break-out hit song? Other songs are equally ensconced in the musical theatre canon: “I Loves You, Porgy”, “Bess, You Is My Woman, Now”, “There’s a Boat that’s Leavin’ Soon”, “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” and more.

From the beginning, Porgy and Bess has proven to be – as director Mumbi Tindyebwa writes in his program notes – “a lightning rod for conversations around race and representation in the arts, questions that are very much alive in our artistic community today.” Gershwin famously insisted on having a fully African-American cast for his 1935 Broadway premiere, refusing to allow any company to perform it in “blackface”. There has also been some discomfort with the story itself being seen as a stereotypical depiction of African-American life. Both issues were addressed in the format of this production. Although advertised as Porgy and Bess in Concert, it was actually at once both less and more than that. It was not the full musical presented in concert format, but rather a selection of the main numbers along with other songs popular at the time of the show’s writing. Narrated by Walter Borden (from a script written by Richard Ouzounian), the framework provided interesting information on the original inspiration for the material, as well as its development from folk songs, to the novel and play by Dubose Heyward, to the musical/opera by George and Ira Gershwin.

Performing the songs in a tight jazz/blues quartet were some of Toronto’s top jazz, blues and gospel performers: Troy Adams, Thom Allison, Neema Bickersteth, Alana Bridgewater, and Jackie Richardson. While the singers were all strong, I wish they had not relied so heavily on microphones instead of letting their voices soar in the great ballads and duets of what is essentially, and was originally meant to be, an opera.

It was an informative and enjoyable evening, though not exactly what I had been expecting. Perhaps the title should have been something more along the lines of “Exploring Porgy and Bess in Concert.” There is a growing appetite across North America, if not also further afield, for concerts that incorporate a scripted framework with some staging and visual elements. One need only look at the success of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Beyond the Score series, which explores the inspiration behind various symphonic works, or closer to home, Alison Mackay’s scripted shows created for Tafelmusik and the Toronto Consort. The “in concert format” is also an inexpensive way to keep older and more obscure musicals in the public eye and happily, Soulpepper has promised more concerts in this style in upcoming seasons.

A Streetcar Named Desire, John Neumeier. National Ballet of Canada, June 19 at the Four Seasons Centre

Of the three “classics revisited” last month, this was the most recent classic, though a revisiting from the 1980s, and also – to me – the least successful of the three. Iconic American playwright Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire is a revered classic of the American Theatre, and though less universal than the other two, equally a tragic tale of love and lives lost, known so well from its great impact and success on both stage and film. Who doesn’t know the famous quote of Marlon Brando agonizingly yelling “Stella!”?

Of the three “classics revisited” last month, this was the most recent classic, though a revisiting from the 1980s, and also – to me – the least successful of the three. Iconic American playwright Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire is a revered classic of the American Theatre, and though less universal than the other two, equally a tragic tale of love and lives lost, known so well from its great impact and success on both stage and film. Who doesn’t know the famous quote of Marlon Brando agonizingly yelling “Stella!”?

There have been a number of ballet versions of the play, but this seems to be the only one that is not a straightforward retelling and instead a comment upon, or reaction to, the original material, as choreographer John Neumeier has said himself in interviews. His primary departure from the original play is to create an entirely new first act, where Blanche, from a bare iron bed in a sanitarium, revisits her past. In a sequence that feels much too long and vague we are shown the beginning of the tragic downturn of her life on the discovery that her husband is in love with another man, followed by his suicide and the decline and fall of her family. It’s an interesting idea but not totally successful, and not helped by the presence of three men in and on and around the bed with Blanche, clearly not part of the wedding or family scene but not clearly belonging anywhere else except, perhaps, in her mind, which ultimately is what we are supposed to realize. Accompanying this act are sparse recorded solo piano pieces by Prokofiev, simple and enigmatic.

In the second act of the ballet, Neumeier returns to the well-known plot of the play, with Blanche visiting her sister Stella, now married to Stanley Kowalski, in New Orleans. The music choice here was completely apt, switching from the more romantic Prokofiev to the jarring and jazzy music of Alfred Schnittke, which the choreographer has said he found perfect for his purposes. Here we see Blanche trying to orient herself to the very different, rougher, modern, working-class style of life that she finds there.

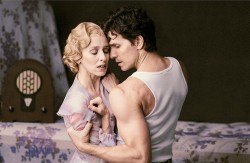

Less dreamy than the first act, the action is faster but still lingers a bit too long in various parts: the boxing scene with Stanley and Mitch for example, and particularly the uncomfortably long and explicit yet stylized rape sequence. These scenes also felt dated for me, and would probably be choreographed quite differently today, even if by the same choreographer. The most effective scene I found was the heartbreaking pas de deux sequence between Blanche and Mitch that begins with a shy presentation of roses, grows to an increasingly romantic sharing of possibility, and then degenerates – after the interruption by Stanley “telling” Mitch of Blanche’s past – into Mitch leaving Blanche broken and in despair. Piotr Stanczyk was in good form as a strident and masculine Stanley, Svetlana Lunkina was delicate and fragile as Blanche, but the standout performance for me was Donald Thom as Mitch, elevating this secondary part into a new revelation of character and story – a striking example of how, in all three of these shows, a classic narrative can be reimagined and redefined with each new production and performance.

Toronto-based “lifelong theatre person” Jennifer (Jenny) Parr works as a director, fight director, stage manager and coach, and is equally crazy about movies and musicals.