This sentence notwithstanding, I try not to use too many personal pronouns when writing. Call it a parasympathetic reflex from my student days writing prosaic, academically sourced theses, but words like “I” and “my” seem too personal and isolating to use even in a communal column and publication such as The WholeNote; and I don’t write editorials (although I do express the occasional opinion or two!). This month is an exception, however, for we begin our two-month survey of the Toronto early music scene with two personal anecdotes – disparate occurrences that, although entirely independent in time and place, share a common, relevant and important theme.

A few weeks ago, I gave a recital at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre. The program for this little concert contained a blend of jazz, minimalist and avant-garde music, including György Ligeti’s Harmonies for organ. After the performance one audience member approached and asked, “Why bother with such music? You could have played that piece (Harmonies) forwards or backwards and we wouldn’t have known the difference!” It was ultimately a worthwhile question and one that many performers face, particularly in the realm of music written in the 20th century and onwards: why bother playing music that people won’t understand, music that is not necessarily tuneful, pretty, or accessible to the masses?

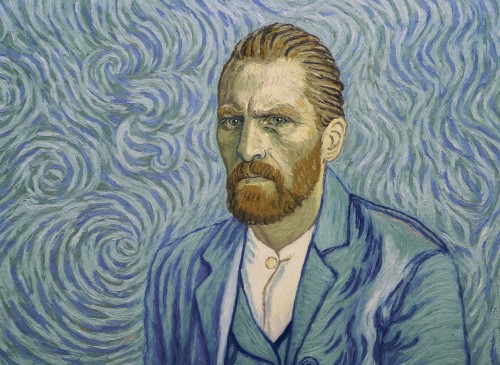

Days after my recital experience, I saw the new film Loving Vincent, an artistically oriented speculative recreation of the last days of Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, incorporating elements of documentary and murder mystery. This film was screened at TIFF Bell Lightbox and is notable because of the way it was made. Each frame – 65,000 of them altogether – was hand-painted in the style of Van Gogh by an international team of artists, then photographed and digitized using animation software, thereby creating a literal motion picture. Before viewing Loving Vincent, I read a synopsis in The Guardian in which the reviewer questioned the painstaking process of producing the film, arguing that an equally visually satisfying production could have been generated using purely digital means without the trouble of hand-painting anything at all. In our digital age, the review queried, why bother with all the unnecessarily painstaking manual labour?

Days after my recital experience, I saw the new film Loving Vincent, an artistically oriented speculative recreation of the last days of Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, incorporating elements of documentary and murder mystery. This film was screened at TIFF Bell Lightbox and is notable because of the way it was made. Each frame – 65,000 of them altogether – was hand-painted in the style of Van Gogh by an international team of artists, then photographed and digitized using animation software, thereby creating a literal motion picture. Before viewing Loving Vincent, I read a synopsis in The Guardian in which the reviewer questioned the painstaking process of producing the film, arguing that an equally visually satisfying production could have been generated using purely digital means without the trouble of hand-painting anything at all. In our digital age, the review queried, why bother with all the unnecessarily painstaking manual labour?

In early music circles, the question “Why bother?” is a relevant one, too. When we look at the frequency with which certain individual works are performed, there are inevitably moments where we question the rationale behind established conventions that have become normalized. For example, now that December is here, why bother playing Handel’s Messiah again across the city – haven’t we been up to our eyeballs in it every year for the past decade? Why bother with another performance of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio or Corelli’s Christmas Concerto? Reprising these works year after year seems to be the bad end of a Faustian pact, the lure of a full auditorium paid off with the ceaseless repetition of the same stuff, taxing our ears with all-too familiar strains of “Hallelujah!,” “Jauchzet, frohlocket!” or some other predictable and overdone work – a festive and wintry Groundhog Day, if you will.

These are thought-provoking queries, many of which are difficult to answer. The questions of “Why?” and “Why bother?” will always be applicable to the arts, particularly when something new and unfamiliar (in the case of Ligeti’s Harmonies) or unusual and idiosyncratic (as we see in Loving Vincent) is put on display, but another little anecdote recounted to me by a former teacher may help answer why we always seem to return to the time-tested Baroque classics in December:

Once a conductor was in a dress rehearsal of Messiah – everyone involved had performed the work many times. One singer was rather lackadaisical about his part and seemed lazy and lacklustre throughout, irking the conductor enough that he confronted him about it afterwards.

“Listen,” the conductor said, “I know you have sung this many times, as I’ve conducted it many times, but you have a great responsibility as a performer. Tonight’s concert may be the first time that someone in that audience hears Messiah. And this performance may also be the last Messiah someone in that audience hears.”

My Grown-Up Christmas List

For many, Messiah is as much a quintessential seasonal favourite as mulled wine and a ten-pound fruitcake. With dozens of performers presenting various Messianic adaptations and interpretations across Toronto and its surrounding areas, it can be a tricky task to pick only one! Fortunately, The WholeNote is here to help: read my recent blog post on notable performances, or search for the word “Messiah” in our online listings to get a list of most of this year’s shows. Whether full-length or condensed, HIP or modern, symphonic or sing-along, we have the Messiah for you.

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio is another classic Christmas composition from the Baroque era, compiled and composed between 1733 and 1734 to celebrate the Christmas season in Leipzig. Although catalogued as BWV248 and now considered a single, freestanding work, this “oratorio” is in actuality a series of six individual cantatas that were performed during the time between Christmas and Epiphany (what we now call the Twelve Days of Christmas) and divided between the Thomaskirche and Nikolaikirche, Leipzig’s two main churches.

Monumental in scope and brilliant in its musical expression of Bach’s beliefs and theology, the Christmas Oratorio is, along with the Passions, the closest Bach came to writing a narrative opera. Geoffrey Butler and the Toronto Choral Society perform the Christmas Oratorio at Koerner Hall on December 6, in what promises to be a welcome respite from the hurly-burly of the commercially overloaded Christmas season.

Continuing their trend of melding old and new, the Toronto Masque Theatre presents their seasonal salon “Peace on Earth” on December 17 and 18. Featuring the performance of baroque Noëls and the Messe de Minuit by Marc-Antoine Charpentier, these Franco-flavoured evenings will explore the simplicity, beauty and joy of the French Baroque Christmas, different in many ways from the immense and intricate forms we find in English and German oratorio.

To complement these French Baroque favourites, TMT also leaps forward into the 20th century with excerpts from The Birth of Christ, a cantata written in 1901 by Canadian composer Clarence Lucas (1866-1947) as well as seasonal readings by from T.S. Eliot’s The Journey of the Magi. With this medley of music and word on display only one week before Christmas, these performances will surely banish the last “Bah humbug!” from even the Scroogiest of curmudgeonly misers.

But Wait, There’s More! A Taste of 2018

Fast forward to January 2018: Belts are loosened an extra notch (or two); turkey leftovers, eggnog and rum hangovers, and the last few sweet treats all linger longer than expected. New Year’s resolutions are resolutely made and broken, and we start looking ahead to the inevitable wintry weather that is to come. If we somehow ignore the temptation to snuggle up with a cup of cocoa and hibernate until March, there are many exciting events taking place across Toronto in January, including two promising projects by Tafelmusik (who might quite reasonably go into hibernation themselves after their busy December!).

The first is the Tafelmusik Winter Institute, a terrific opportunity for those with a passion for Historically Informed Performance. A one-week intensive for advanced students and young professionals, this year’s TWI culminates in a free public performance at Jeanne Lamon Hall on January 10. Featuring music by French composers Lully, Campra, Marais and Rameau, and this performance presents a rare opportunity to hear top-notch music from the height of the French tradition for an unbeatable price.

Over the last few years, Tafelmusik has pushed the boundaries of the early music concert experience with Alison Mackay’s creative multimedia conceptions and collaborations. This positive trend towards HIP-infused modernism continues with Safe Haven, a program exploring the musical ideas of Baroque Europe’s refugee artists, drawing parallels between 18th-century Europe and present-day Canada. At that time of year when the Christmas chestnuts have come and gone, this concert looks to provide a palate-cleansing leap forward in a genre that occasionally seems to specialize in blasé repetition.

Scaramella: While Tafelmusik peers into the future with Safe Haven, period performance group Scaramella looks back in time with their “Ode to Music” on January 27. Featuring Scaramella’s Joëlle Morton and guest virtuoso viol players Elizabeth Rumsey and Caroline Ritchie from Basel, Switzerland, this program uses a variety of 16th-century music for viol consort to explore the impact of the muses on Renaissance composers. This concert provides a wonderful opportunity for viol enthusiasts and novices alike to acquaint themselves with the spectrum of sound these antiquated instruments can produce, living musical relics linking our ears to past centuries.

Scaramella: While Tafelmusik peers into the future with Safe Haven, period performance group Scaramella looks back in time with their “Ode to Music” on January 27. Featuring Scaramella’s Joëlle Morton and guest virtuoso viol players Elizabeth Rumsey and Caroline Ritchie from Basel, Switzerland, this program uses a variety of 16th-century music for viol consort to explore the impact of the muses on Renaissance composers. This concert provides a wonderful opportunity for viol enthusiasts and novices alike to acquaint themselves with the spectrum of sound these antiquated instruments can produce, living musical relics linking our ears to past centuries.

As winter-themed advertising flashes across our smartphone screens and store windows are redecorated with miniaturized villages and resplendent hues of red, green and gold, it can be overwhelming and daunting to find time to attend a concert; despite the seasonal hustle and bustle, I encourage you to explore the vibrant musical offerings that are on display this December and January. Whether you prefer Handel’s Messiah, Tafelmusik’s Safe Haven, a traditional Festival of Lessons and Carols, or any of the other listings in this double issue of The WholeNote, the richness and depth of Toronto’s classical music scene ensures that no concertgoer ever has to ask, “Why bother?”

Happy Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Festivus and New Year, everyone. See you in February! Until then, keep in touch at

earlymusic@thewholenote.com.

Matthew Whitfield is a Toronto-based harpsichordist and organist.