Emails from Cambodia

Earlier this year an email appeared in my inbox with an intriguing invitation. “Join us in celebrating Peter Chin’s last major work, featuring an international cast of dancers and musicians on June 23 and 24 at 8pm, and June 25 at 2pm at Harbourfront Centre Theatre.” The announcement continued, “trillionth i signifies the third eye and beyond, to the trillionth eye, in an embrace of endless ways of sensing, knowing and of being in the world…” and was signed off with “choreography and music composition by Peter Chin.”

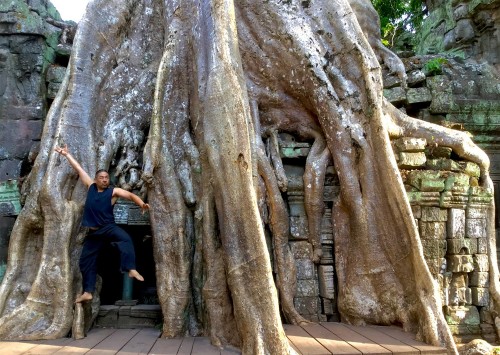

A personal email followed soon after, from Chin’s bucolic Neang Kong Kental Dance Centre, located in tropical Siem Reap, Cambodia (which he opened in 2021) inviting me to join a number of Cambodian musicians in this upcoming Toronto production. What instruments will I play in trillionth i? He mentions gongs, gongchimes, bamboo flutes and instruments typically reserved for ritual occasions. It’s a daunting list, but for the fact that it’s a Southeast Asian- flavoured music landscape we’ve visited together in several of his earlier productions, as we’ll see.

Multivalent

Though he has created over 40 original works for his inscrutably named company, Tribal Crackling Wind, the Jamaican-born, Toronto-based Peter Chin is not a household name in music circles, perhaps due to the range of his many and diverse talents. He has been variously described as a choreographer, dancer, singer, instrumentalist, composer, designer, writer, director and performance artist. He’s all that, if four Dora Mavor Moore Awards, a Gemini Award and the 2006 Muriel Sherrin Award for International Achievement in Dance, among other accolades, is proof.

trillionth i: Production and Cast

I had questions, so on Mother’s Day I called Peter on Zoom leading with “What is trillionth i?”

“The research and creation of trillionth i began in 2017 but its production was delayed for years due to the pandemic,” he replied. “It’s an international dance work with live music performed by Cambodian, Mexican, plus Canadian artists – the latter of course also includes artists with diverse cultural backgrounds.” The 15-member cast includes Jennifer Dahl, Katherine Duncanson, Bonnie Kim, Andrea Nann, Carlos Rivera, Heidi Strauss, Andrew Timar, and Peter Chin (Canada); Marina Acevedo (Mexico); Chy Ratana, Chanborey Soy, Ros Sokunthea, Rasy Hul, Mouern Chanthy and Chea Ratanakitya (Cambodia).

“It’s a work with a global view” Chin explained, “but, given that the majority of artists are Cambodian, it has a distinctive Cambodian dance and music matrix through which it’s being created and shared. In fact, I’m very pleased my film spinoff titled Trillionth i: Transmission is receiving its Asian premiere at the Cambodia International Film Festival this month. It’s a tangible tribute on home turf to the talented contributing Cambodian artists.”

Flashback to the 80s

Interrupting the present story, I’m going to take the liberty to rewind to the 1980s, when I first met Peter Chin. He spent the first part of that decade at York University studying painting, sculpture, video and performance art with Vera Frenkel, music composition with James Tenney, piano with Casey Sokol and creative writing with bpNichol. We had much in common: it wasn’t that far from my own scene. I had studied with Tenney, provided music for a multimedia Frenkel performance, and casually gigged with Sokol at The Music Gallery. Before John Oswald and I launched Musicworks magazine in 1978, my writing was sophomoric. It was the sheer necessity of putting out an experimental music quarterly with international aspirations that incrementally lifted it to the next level.

Enter Gamelan and Composition

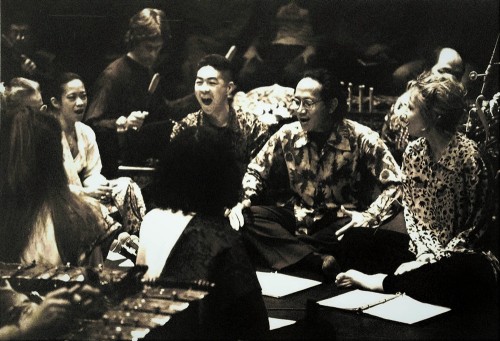

Seventeen years later I formed the community group Gamelan Toronto at the Indonesian Consulate General on Jarvis Street and Peter was there: an eager early adopter. Having already lived and travelled extensively in Indonesia however, it wasn’t really much of a stretch for him. Like me, he had fostered a love for the country’s myriad cultures and peoples. In Gamelan Toronto he took a leadership role singing in the small choir in his strong, focused tenor when the group co-hosted the Gamelan Summit 1997, Canada’s first such festival.

Inspired by the group’s dedication to the rich Javanese gamelan music tradition, it didn’t take him long to choreograph and stage his works Raturaja (1997), Bridge (2001) and Berdandan (2005). They were followed by Mind’s Hammer (2006) with himself as solo dancer and music played by Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan. More remarkable still, he also composed the scores for these works and directed their musical performances – among Western choreographers a skill set as rare as snowballs in Java.

His early compositional talents, as he told me in this month’s Zoom call, were fostered in a particularly musically rich Toronto grade and high school. “I began classical music training at St. Michael’s Cathedral Choir School where for most of the 1970s I was active as a student chorister, pianist and organist. I started to compose polyphonic motets there, several of which were sung in St. Michael’s Cathedral by the choir,” he added.

Where I Come In

To date, I’ve played in eight of Peter’s concert and film productions. Though Sundanese and Balinese sulings (a family of bamboo ring flutes) are my mainstay, I’ve also played kacapi (20-string Sundanese zither) and a wide variety of gongs, bells, metallophones, cymbals and horns in them.

Our last show was You See Us, presented in the Older & Reckless dance series at the Harbourfront Centre Theatre last November. It was originally slated for 20 “older” dancers, three live musicians, and a soundtrack directed by Peter recorded in Cambodia. Frustratingly however, the cast was downscaled after, during rehearsals half the original dancers were sidelined by (hopefully) the last major COVID-19 spike. It came that close to being postponed yet again. Yet we regrouped and somehow managed to finish a beautiful, stirring work-in-progress version.

trillionth i: Big Questions, Challenges and a Premiere

Back to the upcoming production of trillionth i, Peter furnished further insights into the work’s philosophical heart. It’s a search for “our essential oneness,” asking its “multigenerational cast from 8 to 72-years old … to go beyond representation, to engage as dance and music ritual specialists…”

But to what end? Here we come to Peter’s ultimate challenge to his performers. In his online Artist Statement he tasks us to perform “dance and music which literally makes a better world.” I can’t speak for the other performers but it’s certainly not an everyday ask for a musician like me. Performers and audience alike will have to wait until trillionth i premieres at Harbourfront to discover how much of Peter’s ambitious vision this international cast can achieve over three rehearsal weeks in June.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician, composer and music journallist. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.