This summer column focuses on an ensemble so new that at press time it hasn’t played a single concert, and yet with concerts already booked into next year!

This summer column focuses on an ensemble so new that at press time it hasn’t played a single concert, and yet with concerts already booked into next year!

The New Canadian Global Music Orchestra (we’ll call it NCGMO for short) was formed in late 2016 and gives its debut concert at Koerner Hall on June 2, after rehearsing and composing music for months. The orchestra includes 12 professional musicians each hailing from a different country, “from Peru to Burkina Faso to Cuba to Ukraine,” but who currently make their homes in the Toronto and Montreal areas. Then it goes on tour in the summer and fall.

Conceived by Mervon Mehta, executive director of Performing Arts at the Royal Conservatory, and hosted by the RCM, the NCGMO is, in the words of its host, “a major initiative by the RCM which celebrates the cultural diversity and pluralism of our great country as it turns 150, connecting us and communicating in ways that words, politicians and spiritual leaders cannot, and helping us to find a common language.”

To helm this ambitious undertaking, the RCM picked JUNO Award-winning trumpeter, composer and bandleader David Buchbinder as NCGMO’s artistic director. Buchbinder’s career bristles with varied performance and intercultural projects, on both large and small scales. Initially he was known for his music groups, such as the Flying Bulgars, Nomadica and Odessa/Havana, and as the founding artistic director (1995) of the flourishing Ashkenaz Festival. He has subsequently produced the shows Shurum Burum Jazz Circus, Andalucia to Toronto, Tumbling into Light and Jerusalem Salon, as well as award-winning scores for stage and screen.

He was also the founder, in 2010 of Diasporic Genius, founded on the premise that new hybrids can emerge from dramatically different musical traditions and art forms in a city like Toronto. The organization seeks to interweave communities and art forms that are typically estranged, to bring about personal and civic transformation, embodying in action “the notion of strength through diversity.”

All this activity has earned him a reputation as a leading figure in the Canadian world music and jazz scenes. In 2016 Buchbinder was recognised as a “cultural inventor” when he was presented with the Toronto Arts Council William Kilbourn Award for “artistic contributions to creative city building.”

In NCGMO’s official video trailer, Mervon Mehta lays out an ambitious, aspirational roadmap for the project. “We’re going deeper into a holistic [conception] of musical form rather than a fusion of musical styles. This is just what we need right now. We need to show people that, yes, we can work together and form a new entity with people from around the world.”

Buchbinder in the same trailer, as an experienced intercultural music director, is a bit more cautious, but just a bit: “It’s always a bit of a fool’s game to claim you’re doing something in music that’s never been done before – because it’s all been done in a way – but doing a process just like this is pretty rare.” He then proposes two initial roadblocks to success: “First of all, how do you make all these instruments work together? Second…how do you get them to speak to each other?”

Good questions and, without missing a beat, he offers solutions. “Well, you don’t try to make all the traditions directly speak to each other,” he says. Their approach, he explains, is to have the ensemble’s music filtered through each of the individual composers in the ensemble. “My gig” he says “is to coordinate things so that the band has a [cohesive] sound.”

Having explored the ever-changing subject of when and when not to attempt to bridge the boundaries of different music cultures from many angles in this column, I personally recognize and applaud the general goodwill and Canadian multiculturalism at work here. On the other hand, even before its premiere concert, NCGMO has prompted healthy dialogue on social media from invested performers in this field, based on media releases and video trailers. One commentator challenged the notion of “composing” for this combination of global instruments, suggesting a privileging of European orchestral culture at work. How will the compositions produced share credit with those whose cultures include a large proportion of improvisation, or those that interpret melody or structure without an externally imposed roadmap? Furthermore, will the differences between urban and high art cultures vs. rural and vernacular traditions be addressed?

Another concern raised: if you want to work as a single orchestra, compromise is necessary – but whose standard/s will govern? And how will writing music on staff notation as a modus operandi impact on the musicians in the group not fluent in it, or for whom such notation does not work for their instrument or performance tradition? And what happens in terms of the potential watering down and glossing over of the individual musical traditions represented, including those with tunings, tonal modes, idioms and performance contexts which diverge from those commonly practised by more dominant cultures? Furthermore, will some instruments lose things inherent to their cultural and musical identity when subsumed within an ensemble such as this?

Concerns such as these underline how complex and sensitive such a project is, and why it has rarely been tried on this scale. All the more reason, perhaps, for undertaking it as a crucible for their exploration.

Returning to Buchbinder’s initial observation about nothing ever being entirely new, self-avowed transcultural acoustic ensemble musicking – the kind NCGMO does – already has roots in this country and elsewhere. A ready example is the Vancouver Inter-Cultural Orchestra. Founded in 2001, it is going strong today. Before it, both the Vancouver World Music Collective and the ASZA acoustic quartet flourished in the 1990s, encouraging the appetite for hybrid music in the region. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t also mention Yo-Yo Ma’s pioneering, Grammy Award-winning Silk Road Ensemble here. Formed in 2000, it claims performers and composers from more than 20 countries. (The group, which set the bar high for cross-cultural understanding and innovation, was featured in my article Silk Road Stories: Spinning a Musical Web in The WholeNote in September 2015.)

Over the course of the last few months, NCGMO members have shared their music traditions with one another in rehearsals, composition sessions and workshops. I arranged to speak with Buchbinder in person, now that things are moving towards their first performance, about what it has taken to reach this point.

“Selecting the participant musicians was a lengthy process, one which involved a large number of potential candidates. The NCGMO audition call went out last fall. We had three rounds of auditions with more than 100 Canadian musicians, originally from 47 countries, applying to be in the orchestra, ending up with the 12 musicians we have today.”

What were the criteria used to choose the musicians? “We wanted to spread the music traditions represented as widely as possible round the globe,” replied Buchbinder. “We were also looking for musicians with a wide range of musical experience, open minds, and playing at a high and exciting level of musicianship.”

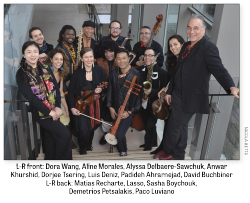

In the end, the chosen musicians include some who are established on the local world music, scene such as sitarist Anwar Khurshid, who also plays flute, esraj, tabla and harmonium, and Brazilian percussionist and vocalist Aline Morales. But it’s only by seeing the complete personnel list, however, that we can get an impression of NCGMO’s aspirational global reach: Luis Deniz (saxophone), Lasso Salif Sanou (Fulani flute, kambélé n’goni, tamanin, balafon, djembe, doum-doum, vocals), Paco Luviano (bass), Demetrios Petsalakis (oud, guitar, lyra, bouzouki, riq, Greek baglama), Padideh Ahrarnejad (tar), Sasha Boychouk (woodwinds, ethnic Ukrainian flutes), Alyssa Delbaere-Sawchuk (Métis fiddling, jaw harp, spoons, vocals); Matias Recharte (drums, percussion, cajón, conga, timbales); and, rounding out the Asian branch of the orchestra, Dorjee Tsering (dranyen, flute, piwang, yang chin, Tibetan vocals) and Dora Wang (bamboo flute, flute, hulusi, xiao, panpipe, ocarina).

I asked him about the biggest challenges of the process so far. “Creating a cohesive ensemble where musicians can connect on cultural and musical common ground,” he said. “Beginning with meetings at the end of last year, we began rehearsals in earnest in January of 2017. We used group-building exercises I’ve developed over the years including a language game.”

(We can see Buchbinder briefly conducting one of these games in the video trailer I mentioned earlier.)

There have been three phases to the group’s ongoing development, he says. “The first includes group building, creating a common language, exploring musical ideas. The second focuses on composition, since most of these performers hadn’t experienced working in this sort of environment, and exploring ways of approaching intercultural musical development. The third involves holding intensive rehearsals and then shaping the works each composer/musician developed. Each member of the group worked on a musical idea; most of the ideas were then arranged by me.”

I asked him how how they had negotiated the issue of notation, which could potentially conflict with the multiple oral traditions represented within the group.

“I was a bit surprised to find that eight of the twelve read Western staff notation well. Notation gives us the opportunity to specify musical intention [and to record it for performance]. Given the limitations of rehearsal time, in this phase of our work we’ve created charts on paper that serve as blueprints for performance. The big challenge is how to have a musical meeting in every piece, allowing each musician’s voice to emerge from among the ensemble – a process which includes adaptation and making space [for the individual within the collective].”

“After all, the notes are only a starting place. I think of the ideal texture as cultural heterophony, where everyone gets to perform with their own accent. The process of defining each musician’s voice is actually happening on two levels. On one level each composition is one person’s own; on the other each other person is putting their own shimmer on it.”

What about future directions for NCGMO? “One of our members, Alyssa [Delbaere-Sawchuk], is Indigenous, and that’s something I want to explore further. One of the essentials of cross-cultural creation is the idea of specificity, of individual identity. I completely believe in the power of intercultural creations, and it is powered by individual stories.”

The emergence of NCGMO signals a growing general societal awareness around embracing musical multiplicity. It also signals the recognition by an elite music organization, focused in the past almost exclusively on Euro-American music, of the reality of changing Canadian demographics and music markets, and the responsibility to broaden its musical landscape.

On the Road

After NCGMO’s inaugural June 2 performance on its RCM home turf, the show goes on the road. On June 30, it opens Toronto’s Canada 150 celebrations at Nathan Phillips Square. Then it travels west down Hwy. 401 to TD SunFest in London, Ontario, in downtown Victoria Park, where on Sunday, July 9, it plays two festival-headlining performances. Begun in 1994, Sunfest is a non-profit community arts organization “dedicated to promoting cross-cultural awareness and understanding of the arts,” and this year its main festival happens July 6 to 9. I can attest it is worth the drive to London to catch the small-town feel and the world music-centred programs.

NCGMO next appears in the evening program on Friday, July 14, at North York’s annual Cultura Festival at Mel Lastman Square. Curated by world-music programmer Derek Andrews, who has been on the world-music file for decades, Cultura is a free family-friendly outdoor festival presenting every Friday evening in July. Expect the eclectic. A sampling: the Korean folk pop of Coreyah, JUNO-winning Okavango Orchestra, and Peterborough Celtic fiddling by Donnell Leahy.

On July 15, NCGMO performs at the Hillside Community Festival held in the idyllic Guelph Lake Conservation Area in rural Ontario. It will give a mainstage performance as well as workshops at this festival that “celebrates creativity through artistic expression, community engagement and environmental leadership.” I attended years ago and eagerly soaked up the positive community vibe in the verdant park setting.

On July 23, the orchestra takes the afternoon stage at Ottawa’s National Arts Centre during the Canada Scene festival, produced by the RCM and presented in collaboration with Ottawa Chamberfest. Canada Scene is a vast festival aiming to be “a living portrait – a daring, eclectic reflection of contemporary Canadian arts and culture.” It includes “1,000 talented artists in music, theatre, dance, visual and media arts, film, circus, culinary arts and more for an extraordinary national celebration.” With some dozen concerts tagged “World” and “Folk,” I’m seriously tempted to visit our nation’s capital to take in the musical wealth. Fall dates have also been announced for NCGMO, including a recording session at the Banff Centre.

I wish the fledgling NCGMO beautiful sounds, exciting experiences and lasting friendships. And I wish all you, dear readers, a relaxing, music-filled summer.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.