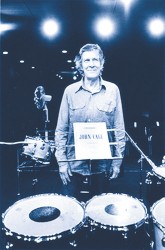

Reflecting on this month’s slew of anniversaries, I am marking on my calendar the 100th year of American composer John Cage’s birth, on September 5, and the 20th of his death. What does Cage the multi-faceted avant-garde modernist, the influential composer, music theorist, author, mycologist, poet, lecturer, musician and master of silence have to do with world music, our column’s purview? This is the subject of the present column’s lead story.

Reflecting on this month’s slew of anniversaries, I am marking on my calendar the 100th year of American composer John Cage’s birth, on September 5, and the 20th of his death. What does Cage the multi-faceted avant-garde modernist, the influential composer, music theorist, author, mycologist, poet, lecturer, musician and master of silence have to do with world music, our column’s purview? This is the subject of the present column’s lead story.

English musicologist David Nicholls, in his 1996 essay “Transethnicism and the American Experimental Tradition,” argues that the influence of musical transethnicism — a branch of experimental music allowing for mixing recognizable music genres often from differing cultures — on Cage’s compositions, is less overt than in the work of some his colleagues such as Lou Harrison, tending to be “ideological ... rather than the musical sounds or techniques.” For much of Cage’s career that may be the case; however there is a significant Cage work composed for a Toronto world music group in the last decade of his long and prolific career that may suggest differently.

My interest in Cage’s music is highly personal: it began in my last years of high school, mediated by shiny new LPs. During my undergrad years at York University this vinyl-based curiosity developed into an active interest. I studied and played his music under the tutelage of Cage’s students and colleagues such as composition professor James Tenney. In the 1970s and 1980s Cage’s avant-garde celebrity was growing and there seemed to be ample opportunity to see him here in person. New Music Concerts brought him to Toronto repeatedly. I also attended a performance of the touring Merce Cunningham Dance Company at the Royal Alexandra Theatre, a company he was associated with for five decades as musician, composer and music director.

Canadian composer Udo Kasemets, an early Cage follower and adaptor, had performed Cage’s Suite for Toy Piano in 1963. Kasemets subsequently brought Cage and Marcel Duchamp to Toronto to perform at the Ryerson Theatre in 1968. By 1981, along with composer Miguel Frasconi, I felt well enough acquainted with Cage’s work to tackle an interview with him, published in Musicworks. My creative intersection with Cage and his work culminated in 1986/87. It was during that exciting time that I witnessed, firsthand, the genesis of Cage’s Haikai, participating in extensive rehearsals of the score and in the premiere performance.

Haikai was composed not for a new music group of Western concert instruments, but for the gamelan ensemble of the Toronto-based Evergreen Club, founded in 1983 by Canadian composer Jon Siddall. The group consisted of eight professional musicians who collectively played a particular type of gamelan called degung, indigenous to the West Javanese region of Indonesia. The Evergreen Club was Canada’s first performing gamelan and by the mid-1980s the group was beginning to make a name commissioning dozens of new works, performing them about town and recording them for broadcast on the CBC.

In 1986 John Cage was approached by Siddall, EC’s artistic director, to come visit its gamelan degung, Si Pawit, a name which in the Sundanese language of West Java means “honourable foundation.” James Tenney (still at York University) was already writing a piece for prepared piano and gamelan degung for an upcoming EC concert. Tenney was a former Cage student and Siddall took advantage of that personal connection to call Cage to inform him of his plan to combine Cage’s 1940 invention, the prepared piano, with gamelan. During Cage’s next lecture trip to Ontario, he visited the Beach neighbourhood of Queen St. E. where Siddall and his Si Pawit resided. I was to take part in Cage’s brief visit, and was on my way down Leslie St., but was unfortunately stuck in a minor gas-station fender bender. The following, therefore, is my, alas, second-hand account of John Cage’s only visit to Si Pawit, which I share with you for the first time, courtesy of my long-time friend and colleague Jon Siddall who served as Cage’s sole host and gamelan degung guide in my absence.

On arrival, Cage set to work exploring the individual characteristic sounds of the Si Pawit instruments with his own hands. In the Cageian spirit of playful experiment he turned the rows of gongs of two of the instruments, bonang and jengglong, upside-down and played their rims with mallets. The resulting unpredictable sounds so delighted him that he scored upended gongs, bowed and coaxed with mallets of graduated hardness, at the heart of his new work. His imagination wandered one step further: he wondered about spinning the gongs on the floor on their knobbed centres! Siddall knew then that Cage “was hooked.” Cage however stopped himself from taking that particular radical action, thinking out loud that it might not be beneficial for the instruments.

Cage worked on Haikai (1986) during a busy time in his career. He had begun work on his first opera project, Europeras 1 & 2, and I find it remarkable that he made the time to prepare a new work for a young, as yet little proven, gamelan group in Toronto. Perhaps it was Evergreen Club’s dedication to numerous rehearsals to finesse new compositions that secured Cage’s dedication to the project. In three weeks the beautifully hand written score — even the organic looking staff was drawn by Cage’s pen — was completed and sent. The work is dedicated “for Si Pawit, gamelan degung of the Evergreen Club.” This collegial dedication reveals Cage’s focus on the individual characteristics of this particular gamelan (Si Pawit), and also honours the performing group, the musicians who bring the score to life.

The commission didn’t go unnoticed by the local media. Toronto Star music critic William Littler, in his preview article “Ensemble to Debut Asian-influenced Cage Work,” takes a bemused, if friendly, stance. “There, in a second-floor Richmond St. studio the other night, sat eight men in stocking feet, squatting before a collection of bronze gongs and xylophones, wooden drums and a single flute ...”

For all of its innovation — the gongchimes turned upside down, bowed gong rims and what the score calls “Korean unison” (essentially chords of unmeasured entry, dynamic and duration) — the score reflects in its open spirit aspects of idiomatic gamelan practice with considerable sensitivity. This is a surprisingly canny achievement for a composer who had not formally studied any sort of gamelan instrumentation or had musical practice in it. Haikai does however bear the earmarks of two of the structural forms Cage adopted from Asian literary sources and repeatedly used in his compositional method: the I Ching, and haiku, the Japanese poetic form. The poetic haiku structure typically consists of the syllable count 5:7:5 spread over three lines. Cage adapted this structure in Haikai, through hand gestures indicating silences, notated in the score in the conventional manner, by fermata.

In Evergreen Club gamelan’s April 5, 1987, premiere performance at Toronto’s Premiere Dance Theatre, it is precisely during these fermata-marked moments in Haikai, when the performers are attentively “resting” yet actively listening, that the real Cageian magic emerges. It is only then that the customary invisible wall between performers and audience, and the physical one between the concert hall and the sounds of the outside world, become permeable, and are able to intermingle. The delighted group director Siddall acknowledged, “It is different from anything we have ever performed ... For me, it’s like nature, like a walk in the forest, where there is randomness but a sense of organization as well.”

In Evergreen Club gamelan’s April 5, 1987, premiere performance at Toronto’s Premiere Dance Theatre, it is precisely during these fermata-marked moments in Haikai, when the performers are attentively “resting” yet actively listening, that the real Cageian magic emerges. It is only then that the customary invisible wall between performers and audience, and the physical one between the concert hall and the sounds of the outside world, become permeable, and are able to intermingle. The delighted group director Siddall acknowledged, “It is different from anything we have ever performed ... For me, it’s like nature, like a walk in the forest, where there is randomness but a sense of organization as well.”

The following morning, the music critic Ronald Hambleton of the Toronto Star was intrigued, if less delighted, writing in an ironic tone, “They used to praise the poet Coleridge, who could bore his friends by talking non-stop for hours, for his occasional ‘brilliant flashes of silence.’ But John Cage, the innovative 75-year old American composer, has a gift for prolonged silences broken by a few brilliant flashes of musical sound. He stretched that gift to a full 25 minutes of what he called ‘events’ in the eight parts of his Haikai ... ”

From today’s vantage point, what do we make of the legacy of this 26 year old work? For one thing, it marks a rare moment when the career modernist John Cage connected with a new/world music group, one of his few works dedicated to Canadian performers. For another, Haikai turns out to be Cage’s only composition for gamelan. Radios, turntables, electronics, conches, cacti and paper aside, in much of his extensive oeuvre Cage primarily composed for Western musical instruments and ensembles. In Haikai, however, he made a significant exception, expressly scoring for an Indonesian gamelan degung. The work stands up as an effective work for the gamelan instruments it was written for as well as accurately reflecting core mature Cageian philosophical notions.

As for the Evergreen Club (called the Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan since 2000), it has not forgotten Haikai, Cage’s gift. This season, ECCG is celebrating not only its unique connection to John Cage on his 100th, but also surviving 30 years ourselves! ECCG is programming three concerts of works later this season, featuring works by Cage, Harrison, Tenney and Canadians including Gordon Monahan, to be performed by the emerging Toronto-based percussion ensemble TorQ along with ECCG’s gamelan.

Ashkenaz: Speaking of 30th anniversaries, mazel tov to Finjan, the Winnipeg klezmer revival pioneers! The well-known band plays in the Ashkenaz Festival, Harbourfront Centre, Saturday September 1 at 8pm on the Westjet stage. Ashkenaz, in this year’s programming, focuses on the diversity of Jewish music, art and artists from around the world, straddling the Labour Day weekend, a time which sparks atavistic fears of the end of summer! So visit Harbourfront and enjoy some of the best diasporic music this season before the summer fades altogether into a faint pleasant memory.

I can only list a few highlights here, so I will focus on music new to me. September 1: Veretski Pass, a trio from California, offers Carpathian, Romanian, Polish and Ottoman styles, mixed with dances from Moldavia and Bessarabia, Hutzul wedding music from Ruthenia, and Rebetic melodies from Smyrna, all woven together with original compositions; and Opa!, a hot post-Soviet “world music party band,” flavouring its vodka with klezmer, reggae, ska and funk, rocks out the night. September 2: the eight-member group Shashmaqam performing classical and folk music of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and the liturgical repertoire of the Bukharan Jews; Abayudaya, representing the musical traditions of Uganda’s Jewish community; and Israeli Shye Ben Tzur whose music is pithily billed as “East Indian Jewish Qawwali.” The festival wraps on Monday September 3 with a performance by Mexico City’s Klezmerson, interpreting Jewish klezmer music from its Mexican viewpoint. Please visit The WholeNote listings and the Ashkenaz Festival’s own well-appointed website for details.

Two more: Moving on, Sunday September 9, the Music Gallery hosts a concert called Afro-European Soundscapes, featuring Werner Puntigam, Matchume Zango, Evelyn Mukwedeya and Memory Makuri. The latter two Zimbabwean musicians have performed with the stars Thomas Mapfumo, Stella Chiweshe, and many regional bands. Part of the Music Gallery’s New World Series, this concert is co-presented with Toronto’s Batuki Music Society. It is billed as “an interactive encounter between South and East African inspirations, European tonalities and electronic transformations accompanied by visual commentary.”

On Saturday September 22, the Brotherhood Concert Series presents two choruses, the Ukrainian Bandurist Chorus (Detroit), and the Hoosli Ukrainian Male Chorus (Winnipeg) at the Ryerson Theatre. These Ukrainian male choruses, North America’s finest, have as an integral part of their sound an orchestra of banduras, the zither-lute which is often called “the voice of Ukraine.”

Small World Music: We have become so used to Small World Music’s Fall Festival ushering in the new season with an ambitious array of global talent that it is hard to believe this year marks the 11th iteration of the event. Consisting of ten concerts in six different venues, the 2012 Fall Festival launches September 20 at Lula Lounge with two groups: The Battle of Santiago mashes Afro-Cuban rhythms, rock guitar, dub bass and a sax and flute duo into what they call Afro-Cuban Post-Rock; and dance-party band Rambunctious, whose lineup is described as “Nine horns + one drummer = dance party” follows. Be prepared to dance!

The next day Fanfare Ciocarlia, a 12-piece Roma brass band takes The Hoxton stage. Beginning as a Romanian wedding band they have played over 1000 concerts in 50 countries, featuring an audience-winning formula of high velocity, high energy precision playing, enhanced by close miking and intense PA volumes, and wild virtuosic solos. Toronto’s Lemon Bucket Orkestra, our own “Balkan Klezmer Gypsy Party-Punk Super Band” opens.

September 22, Small World presents a daylong free “festival within the festival” at Dundas Square. Just a few of the acts: Jayme Stone, Bageshree Vaze, Aline Morales, Kendra Ray, Maracatu Mar Aberto, Lemon Bucket Orkestra and The Battle of Santiago.

September 23, the venue is the more intimate Glenn Gould Studio with a concert featuring Toronto’s Azalea Ray, only student of ghazal maestro Fareeda Khanum. Armed with North Indian classical vocal training, she performs in several Hindustani music genres. But it is her renditions of poetry-rich ghazal songs in her trademark rich alto that I am most looking forward to.

September 25 at the Lula Lounge the Lisbon quartet Deolinda delivers Portuguese fado music with a contemporary twist. They neither wear all black, use a Portuguese guitar, nor indulge exclusively in the untranslatable core ethos of “saudade.” In fact their often humorous and socially challenging songs and performances have been radically described as “happy.” There’s a concept!

Space permits even less detail on the rest: September 26, still at Lula, Toronto’s Jorge Miguel Flamenco Ensemble offers “Spanish Flamenco guitar with a Canadian accent.” The following day the young cimbalom soloist Yura Rafaliuk performs Ukrainian folk music, along with the ubiquitous Lemon Bucket Orkestra. Javier Estrada, among Mexico’s most in-demand electronic dance music producers, brings his “pre-Hispanic dubstep” to the Wrong Bar on September 27. Toronto-based Vesal Ensemble showcases their repertoire of Persian classical as well as Kurdish, Lori and Azeri ethnic music at the Glenn Gould Studio on September 28. And September 30 at the Lula Lounge the Small World Festival closes with rousing party music provided by Toronto’s practitioners of two Northeastern Brazilian song and dance genres: community group Maracatu Mar Aberto offers maracatu, a powerful living tradition of drum, shaker and bell rhythm laced with a through-line of song; and Maria Bonita & the Band perform forró, with its mix of vocals, accordion, fiddle, guitar, flute and percussion.

(I attended a party last night at which just a few members of Maracatu Mar Aberto played. While a friend there told me their powerfully loud drum sounds immediately corrected his previously upset stomach, I believe my ears are still ringing.)

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.