This time last year, the opera community was celebrating as companies large and small started to announce their first “normal” year of programming. Even as live performance began creeping back after the initial lockdowns, opera presenters struggled to balance reduced seating capacities and ticket sales, and shutdown-related revenue loss with the budgets needed to mount full scale productions – especially those presenters whose audiences have grown accustomed to productions with full operatic scale.

This time last year, the opera community was celebrating as companies large and small started to announce their first “normal” year of programming. Even as live performance began creeping back after the initial lockdowns, opera presenters struggled to balance reduced seating capacities and ticket sales, and shutdown-related revenue loss with the budgets needed to mount full scale productions – especially those presenters whose audiences have grown accustomed to productions with full operatic scale.

Now, artistic directors and creative teams have a new balancing act to manage – “making up for lost time” against getting “back on track” with creative plans that are often created three or five years in advance. This with the age-old challenge any opera (or music) presenter faces in any normal season: how to balance the need for familiar, fan-favourite productions, (which are good for ticket sales), with the desire or mandate to present lesser- known works, or commission new operas and productions from composers and directors who continue to move the art form forward.

We sometimes tend to think of opera as a very formalized and set tradition, but but it has built into it a long history of “revising the creative plan” – by directors who recontextualize historical works to reflect contemporary issues; by artists and opera organizations who continue to refine, evolve and build the way that opera is created and performed; and sometimes by composers themselves, of their own volition. All facets of this visioning and revisioning are on display this fall in Toronto’s opera community.

The Canadian Opera Company has long used the model of co-producing with other companies to share the substantial costs of creating and producing large-scale productions. They also pair their operas strategically – running something well-known to audiences, or remounting a successful past production concurrently with something lesser known, or occasionally more contemporary or most often, significantly restaged and reinterpreted. This is beautifully illustrated by their first pairing of operas this fall: Puccini’s La Bohème and Beethoven’s Fidelio, opening Sept 29 and Oct 6 respectively. Puccini (and Bohème) are sure-fire winners here. Bohème was in the COC’s very first season (before the company even had its current name). Since 2008, there have been four productions of that Puccini opera alone. Add Tosca and Madama Butterfly to the mix, and it’s not surprising that there have been only six seasons since 2008 where the company didn’t present one of Puccini’s works.

Beethoven’s music is arguably to classical music audiences what Puccini is to opera, but Beethoven only wrote one opera, so it’s been a 15-year wait for fans of his beautiful Fidelio. After 1805 when it first premiered, he wrote three separate new overtures for it, quibbled with producers about several iterations of the final title, and in 1814 when the final version premiered, swore he would never write another one. On his deathbed, he spoke of the work saying “of all my children, this is the one that cost me the worst birth-pangs, the one that brought me the most sorrow; and for that reason it is the one most dear to me.”

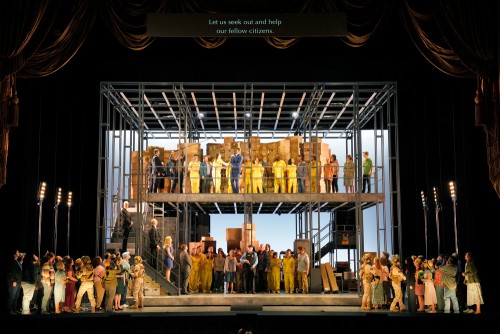

While Fidelio doesn’t make the rotation as regularly as some works, its themes of loyalty and justice have meant that it tends to re-emerge at times of political and global turmoil, re-visioned through a compelling contemporary lens. Director Matthew Ozawa embraces the legacy and seizes the opportunity with both hands, in this new co-production with San Francisco Opera. Originally set in a prison, and originally inspired by the French Revolution (contemporary to Beethoven’s time), this modern re-imagining sets the story in a “undisclosed detention centre in the near past or near future,” and is rooted in the resonances Ozawa found in the material: images he was seeing in 2018 of detention centres in the US and elsewhere – including repurposed Japanese internment camps like the one where his father was born during World War II. The design uses levels, fences and screens to show the hierarchies and bureaucratic machinery involved in imprisoning and silencing people.

Originally slated to open the 2020/21 SFO season, with the COC following suit shortly thereafter, the pandemic has meant an additional wait to see this compelling concept brought to life! (The set has not been gathering dust though. Elements of it were repurposed for SFO’s pandemic drive-in production of The Barber of Seville.)

Opera Atelier’s Orpheus: There are three different versions of Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice – two by the composer himself, but in this case the changes reflected factors other than the composer’s changing feelings about the work – factors such as changing musical tastes and conventions, cultural differences between different countries’ operatic traditions, the standardization of tuning and, above all, who got to play Orpheus. The 1762 version in Italian was written for a castrato; Gluck’s 1774 French reworking ceded to the French preference for their heroes to be high tenors; and in 1859, Hector Berlioz adapted the role to be sung by a contralto.

Opera Atelier has, it seems, explored all three versions of the opera: Gluck’s original Italian version in 1997; the 1774 French-language adaptation in 2007 (with tenor Colin Ainsworth, in the words of one critic, successfully “singing his way into and out of hell”); and most recently, in 2015, Berlioz’s revised score, with all of the main roles sung by women: mezzo-soprano Mireille Lebel as Orpheus, soprano Peggy Kriha Dye as Eurydice and Meghan Lindsay as Amour (Cupid).

Opening their 2023/24 season, Ainsworth returns to the role (and the 1774 adaptation) alongside soprano Mireille Asselin as Eurydice, and soprano Anna-Julia David, making her company debut as Amour. (Oct 26 - Nov 1.)

Tapestry Opera knows better than some that in order for an opera to reach fan favourite level, people need to see it. New, contemporary and diverse voices must reach the new, contemporary and diverse listeners in order to achieve enduring relevance over time. The company understands the importance of exploring themes, events and modern mythology that have shaped a new generation of composers. It also understands the importance of partnering with other creative organizations and producers to support artists through the extended creative process necessary to achieve these goals.

Rocking Horse Winner, based on a 1926 short story by D.H Lawrence, is sharply relevant to modern questions about capitalism, and the unconscious ways we pass on our hopes, dreams, fears and traumas to our children. Initially a collaboration between Scottish composer Gareth WIlliams and Canadian librettist/writer Anna Chatterton as part of Tapestry’s LibLab program, it was completed through a residency with Scottish Opera and premiered at the Berkeley Street Theatre in 2016 – a production that earned five Dora awards.

A partnership with Crow’s Theatre – not exclusively an opera presenter – to remount the production in spring 2020 seemed poised to bring the work to new audiences, until the pandemic forced the cancellation of the run. Rather than dimming the lights, Tapestry, the creative team, and the artists, pivoted to create a recorded version of the opera, which made it’s broadcast debut on Saturday Afternoon at the Opera on CBC, introducing it to listeners across the country, many of whom will undoubtedly be excited to see it in living, breathing form during its eight-show run in Toronto at Crow’s Theatre (Nov 1-2). For those unable to make the trip (or unable to get tickets), you can now access the recording on Tapestry’s Bandcamp.

Ariella: If the return to more normal programming felt miraculous last season, there is a promising new trend, birthed by the lockdowns, to begin watching out for. The lockdowns were traumatic, professionally and creatively for the music community, but for many artists and creators, it brought a period of intense creativity, with time to focus on process without worrying about impending presentation deadlines. Now, as many presenters are entering their second “normal” season, we are beginning to see some of these process-driven new works coming to fruition and taking their first public steps in novel ways.

Composed in 2021, Ariella, a new opera by Jaap Nico Hamburger, is based on the novels of Dutch author Ariella Kornmehl, with a libretto by Thomas Beijer. Toronto audiences (along with audiences in Montreal, Quebec City and then in Israel) will have opportunities to see this work in concert or semi-staged contexts before it makes its official premiere at Lincoln Centre in November 2024. The Toronto stop at Koerner Hall features excerpts from the opera paired, following the intermission, with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2. It’s an intriguing pairing and a wonderful public opportunity to see what an opera looks like as it enters a critical stage on its journey to a more finished form.

Opera by Request: For as long as I can remember, College Street United Church has been a home for music, theatre and opera at every level. It’s a perfect space for Opera by Request’s enduring model: two or more singers identify a role or opera they want to have the opportunity to learn and perform. After identifying a director, they form a collaboration to present the opera with support for casting other roles, rehearsing, coaching and performing the piece in concert with a supportive audience. Mozart’s Idomeneo takes the stage on October 28, and Verdi’s Rigoletto on November 10.

Sophia Perlman grew up bouncing around the music, opera, theatre and community arts scene in Toronto. She awaits the arrival of her copy of The WholeNote to Hornepayne, Ontario, where she uses it to armchair travel and inform her Internet video consumption.