I believe that theatre is at its most exciting when it is taking chances and pushing at the walls that define genre. Even if the risks taken don’t pay off 100%. The world premiere of Orphan Song by Canadian playwright Sean Dixon at Tarragon Theatre is a case in point. Orphan Song sits in an imagined prehistory (40, 027 BCE) where a Homo sapiens couple, Mo and Gorse, take in a Neanderthal child and embark on a journey filled with danger, unexpected mayhem, and discovery.

I believe that theatre is at its most exciting when it is taking chances and pushing at the walls that define genre. Even if the risks taken don’t pay off 100%. The world premiere of Orphan Song by Canadian playwright Sean Dixon at Tarragon Theatre is a case in point. Orphan Song sits in an imagined prehistory (40, 027 BCE) where a Homo sapiens couple, Mo and Gorse, take in a Neanderthal child and embark on a journey filled with danger, unexpected mayhem, and discovery.

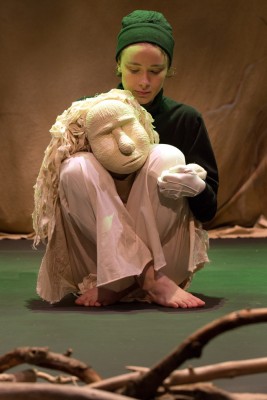

Stories set in prehistoric times are notoriously difficult to pull off without invoking nervous laughter. On opening night there was an initial hesitation from the audience in accepting the simplified, stilted, language of these early human characters, and yet this hesitation dissipated in the face of the absolute conviction of the actors who give themselves wholeheartedly to the simplicity of diction and wide brush strokes of communication necessary. Sophie Goulet’s performance as Mo was superbly grounded, as was the magical work of puppet master Kaitlin Morrow, not only as the Neanderthal child Chicky, but as the creator of the stunning puppets and master teacher of the puppetry technique in the show: the excellent team of puppeteers brings compellingly to life not only the beguiling Neanderthals, but a wide range of wildlife from the small and unthreatening hedgehog to the terrifying hyenas and more.

More than anything, this is a play about developing minds and consciousness, language and thought visibly changing and growing as we see Mo and Gorse fight to survive in their harsh world. Their decision in a “lightening stroke of inspiration” to adopt the Neanderthal child in a gesture of love and longing leads to new leaps of development as they fight as a new family to better understand each other. Along the way this story of one family becomes an analogy for what is possible if we truly strive to communicate, to learn from others instead of turning away from those who are different.

More than anything, this is a play about developing minds and consciousness, language and thought visibly changing and growing as we see Mo and Gorse fight to survive in their harsh world. Their decision in a “lightening stroke of inspiration” to adopt the Neanderthal child in a gesture of love and longing leads to new leaps of development as they fight as a new family to better understand each other. Along the way this story of one family becomes an analogy for what is possible if we truly strive to communicate, to learn from others instead of turning away from those who are different.

Language, the tool of communication, is very much at the heart of Dixon’s play. His collaboration with sound designer and music director Juliet Palmer and the cast results in a rich aural world contrasting the simple recognizable language of the early humans with the wonderfully birdlike musical language of the Neanderthals.

I was so intrigued by the levels of language creation and sound design throughout that I reached out to the playwright and sound designer to find out more about both the inspiration behind the play and the choices they made in the development and rehearsal process. Our conversation follows (edited for length).

WholeNote: What inspired you to write this play, particularly to go so far back in history to find the right setting?

WholeNote: What inspired you to write this play, particularly to go so far back in history to find the right setting?

Sean Dixon: I like to imagine that I was depicting the first time that a child sought to test the adults that were adopting her. And I wanted to dramatize the courage and peril of forging attachment in such a situation by setting it in an isolated wilderness among a family that was being shunned just for trying it.

What process did you follow to create the wonderful soundscape for the world of the play?

What process did you follow to create the wonderful soundscape for the world of the play?

Juliet Palmer: After such a long hiatus from the theatre and concert hall, I was excited for the performers to create the sound world live with their voices. (And the few places with prerecorded sounds have also been created vocally by the cast.) In rehearsal we delved into the calls and movement of the birds and animals that feature in Sean’s script, as well as the ever-present ocean that the Neanderthals are walking towards. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library was invaluable as we channelled our inner blackbirds, pied butcherbirds and hermit thrushes. Hyenas, bears, hedgehogs, rabbits – we learned them all!

How did you approach the question of finding or creating contrasting languages that would seem authentic for the early humans and the Neanderthals?

SD: For the humans, I wanted a limited language. But I didn’t want to be arbitrary about it, so I talked to a friend, Susana Béjar, who is a professor of linguistics at the University of Toronto, and she recommended that I look up a comparative linguistic tool called the Swadesh list – it’s a list of 200 words that form basic ideas which would be fairly consistent across cultures. It gets used to study and compare early language forms.

For the Neanderthals, I was inspired by the Steven Mithen book, The Singing Neanderthals, to create the impression of a language inspired by birdsong. Again, I didn’t want to be arbitrary, so I found an iPad app that rudimentarily transmuted recorded sound into sheet music and I fed a lot of birdsong into it. I used a Midi Player to listen to what I had gathered, then isolated bits that were meaningful to me, combined them with mnemonic text and pasted the musical staves into the body of the text. Finally, I put a note at the start of the play explaining this process and advising performers to interpret these impossible bits of sheet music as a point of departure to their language exploration.

JP: When I left Aotearoa/New Zealand 30 years ago it was to intern with Meredith Monk in New York. Her operas and songs often use invented language, sounds and vocables, so I had a surprising sense of coming full circle with Sean’s play. In preparation for rehearsal, I read a lot about the evolution of music and language – it seems that both communities may have had some form of language at this point in time, but beyond that, our understanding wanders into speculation and the imagination.

I love the contrast Sean sets up between the prosaic and yet surprisingly poetic vocabulary of Homo sapiens and the invented sing-song language of Homo neanderthalensis. Birds and whales both sing songs with both structure and syntax, so it makes sense that the language of the Neanderthals finds inspiration in this repertoire. I also love the way Sean made his own birdcall words – birders will recognize this practice of making the strange familiar through strings of nonsense syllables.

How much did your initial ideas change/develop over the course of rehearsals?

SD: The major change in rehearsal was that I revealed my sources to Juliet: i.e. when a bit of Neanderthal text had been derived from a common blackbird, I revealed that to her, so that she could explore those sounds on her own. Other birds that were revealed included the pied butcherbird, the hermit thrush, ivory-billed woodpecker, the Kaua’i ‘ō ‘ō bird and (not a bird) the humpback whale.

JP: Connecting the actors directly with the sources – field recordings of birds and animals was a huge breakthrough and much more in keeping with our roots as human listeners and sound-makers. Musical notation has its benefits, but it can be a barrier to listening to the complexity of the world around us. Another breakthrough was realizing that the audience needed to see the performers creating the sound world vocally. They’re now only rarely making sound offstage. For me this underscores the act of storytelling that we’re embarked upon. We’re inventing a world with our voices.

Orphan Song continues in the Main Space at Tarragon Theatre until April 24. www.tarragontheatre.com.

Jennifer Parr is a Toronto-based director, dramaturge, fight director and acting coach, brought up from a young age on a rich mix of musicals, Shakespeare and new Canadian plays.