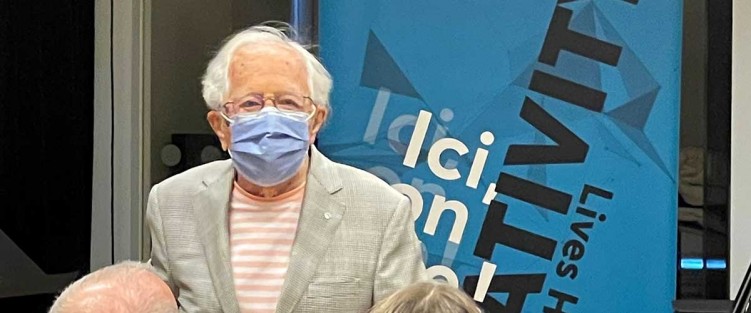

On Friday, September 9 there was a celebration of a book, and of a musician, and of a whole string of numbers, including 17 and 95. It took place within the cozy confines of the Canadian Music Centre, in the space of one hour give or take a half on either side. The book is the 17th published by John Beckwith, who doggedly refused to allow recognition of his 95th birthday, since it took place exactly one-half year ago, and who quibbled in good humour over the accuracy of the number 17. “I’m not sure they were all books…” and with utmost comic timing, added “I think some of them were pamphlets.”

On Friday, September 9 there was a celebration of a book, and of a musician, and of a whole string of numbers, including 17 and 95. It took place within the cozy confines of the Canadian Music Centre, in the space of one hour give or take a half on either side. The book is the 17th published by John Beckwith, who doggedly refused to allow recognition of his 95th birthday, since it took place exactly one-half year ago, and who quibbled in good humour over the accuracy of the number 17. “I’m not sure they were all books…” and with utmost comic timing, added “I think some of them were pamphlets.”

The evening was introduced by Beckwith’s friend and vital collaborator, Robin Elliott. The printed program mentioned that opening remarks would be given by Beckwith himself, so one assumed (wrongly as it turned out), that John had asked Robin to take the lead. He sat down and the first of two performances took place. Once the singing stopped, Robin stood to ruefully ask if John would in fact still like to make the remarks he had planned. Which, of course, he then did, coming out with the “pamphlets” zinger along with a few more delightful digs at his own and our expense. “I hope you’ll enjoy reading it…and if not I believe there are some pictures…” We were eating out of his hand.

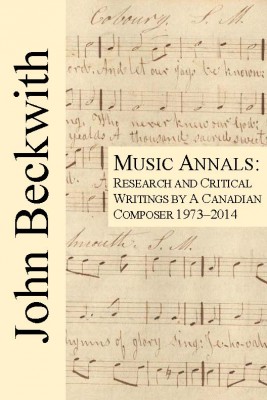

Beckwith is modest and self-deprecating, which is no surprise to any who’ve worked with him. He simply won’t give in to age, or inertia, or anything else one might associate with the notion of living well into one’s tenth decade. The book’s lengthy title is Music Annals: Research and Critical Writings by a Canadian Composer 1973-2014. Call it Volume II. (Elliot noted in his remarks that this book follows an earlier collection, underlining that this was only a selection from among many pieces not yet bound together.) Add to that, since the evening naturally included musical performances, he continues to draw up delightful, witty, challenging and profound music for today’s performers.

Chapter and Verse (2017-18) is a setting of the poetry of Paul Dutton, whose wordplay and wit mask some dark thoughts indeed. Two sopranos (the equally delightful Sara Schabas and Caitlin Wood) sing birdlike antiphons whilst whirling about the dark woods provided by Rory McLeod’s viola. Dutton loves a good puzzle, as must Beckwith. One through Twelve play about in the last three songs, which are drawn from his collection The Book of Numbers; the first text is a poem addressed to M.C. Escher!

Chapter and Verse (2017-18) is a setting of the poetry of Paul Dutton, whose wordplay and wit mask some dark thoughts indeed. Two sopranos (the equally delightful Sara Schabas and Caitlin Wood) sing birdlike antiphons whilst whirling about the dark woods provided by Rory McLeod’s viola. Dutton loves a good puzzle, as must Beckwith. One through Twelve play about in the last three songs, which are drawn from his collection The Book of Numbers; the first text is a poem addressed to M.C. Escher!

During the same period, Beckwith was commissioned by the talented duo of pianist Edana Higham and percussionist Zac Pulak, together known as SHHH!! Ensemble. Meanwhile explores the beauty of folk melody, or perhaps simple devotional song, expressing grief by the end of the work. I thought of an old vine-covered stone structure brought suddenly down by the wrecking ball. Musically modern and deeply expressive, SHHH!! play it like they own it, which in a sense they do; they clearly love performing it and do so with complete assurance and mastery. The duo will be back to release their first CD on October 29; Meanwhile is the title track. Their star continues to rise with news that their next project has already been green-lit.

But the book? What of the mind that communicates in words as well as in musical sounds? It’s early days and I am a slow reader. Beckwith chose the title carefully in reference to the work of a 19th-century French Canadian cleric named Thomas-Étienne Hamel. Hamel’s contribution to Franco-Canadian folkloric study was a collection of colloquial songs in a notebook titled “Annales Musicales du Petit-Cap.” One section in Beckwith’s collection describes and annotates the work of Hamel, and elsewhere he refers to it while discussing other scholarly study. Beckwith could well lay claim to various titles: academic researcher, music critic, polemicist, and of course composer. Often through the pages of the collection, carefully selected and annotated by Elliott, he sheds personal labels, and reminds the reader or listener (some selections are transcribed talks) that he remains committed to the work of composing and writing, but fundamentally considers the title “musician” to be sufficiently descriptive.

Mr. Beckwith’s curiosity and commitment to study make his book essential reading to any interested, as he so passionately is, in Canadian music making, especially that of the dominant settler cultures. But his wit and scathing humour make it a delight to read, especially in two letters he addressed to The Globe and Mail in the 1970s. The reader should be ready for a hearty chuckle at the expense of music critics overly fond of vapid verbiage. The critics should take note and tighten up their style; and their acuity.

Max Christie is a Toronto-based musician and writer. He performs as principal clarinet of the National Ballet Orchestra when restrictions allow, and otherwise spends too much time on Twitter, @chxamaxhc.