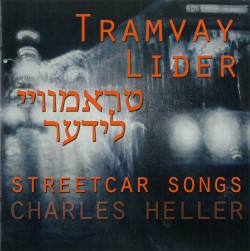

Charles Heller – Tramvay Lider

Charles Heller – Tramvay Lider

Charles Heller – Tramvay Lider

Charles Heller; Bram Goldhammer

Independent (ecanthuspress.com)

Riding transit at rush hour or late at night is rarely fun (save the rare times one encounters live music and dancing on a subway car). A sea of weary, sallow faces (is it the lighting?) can certainly make one feel equally grey and tired but it must have been far more grim during the Great Depression in Toronto. One streetcar conductor, Shimen Nepom, member of a far-left group known as the Proletarian Poets, decided to mine his oftentimes frigid and tedious journey by turning his experiences into a set of Yiddish poems entitled Tramvay Lider (Streetcar Songs), published in 1940 by the Toronto Labour League. Seventy years later, composer Charles Heller learned of Nepom through Gerry Kane, a columnist with the Canadian Jewish News who remembered meeting Nepom when he was a young boy riding the streetcar with his father. Heller then researched the poems, set them to music and now performs them eloquently, yet characteristically on this recording, accompanied by pianist Bram Goldhammer and cellist Rachel Pomedli. The music evokes the clattering tracks, the ringing bells, the bitter winds, but best of all, the poignant stories of the great variety of people who rode the College streetcar back then.