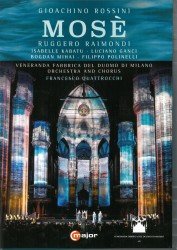

Rossini: Mosè - Raimondi; Kabatu; Ganci; Mihai; Polinelli; Veneranca Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano; Francesco Quattrocchi

Rossini – Mosè

Rossini – Mosè

Raimondi; Kabatu; Ganci; Mihai; Polinelli; Veneranca Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano; Francesco Quattrocchi

Cmajor 735308

This was one of the events specially created for the Milan Expo 2015 that coincided with the 150th anniversary of Italian Unification and what better way to celebrate than to perform an opera in the magnificent Gothic cathedral, Duomo di Milano, that took 600 years to build. The majestic interior became awash in cascading multicoloured curtains of light giving an impressive backdrop to the action.

The original opera, well over three hours long, Mosè in Egitto by the 24-year-old Rossini, was written for Naples. He later revised it for Paris and turned it into French (Moise et Pharaon) thereby losing a lot of the originality and freshness of the original. The creators of this particular event in their wisdom used this second version (translated back into Italian) and condensed it into a one-and-a-half-hour “semi-staged sacred melodrama” of overblown and repetitive religious scenes of divine miracles, dispensing with much of the love story, the human drama and the wonderful music that made this opera a success and caused it to survive for nearly 200 years. Fortunately, the immortal Prayer Scene at the banks of the Red Sea was kept, ending the show on a positive note.

This being in Italy and especially Milan, the mostly young singers are all excellent, their voices gloriously resounding in the spacious acoustics of the cathedral. Isabelle Kabatu as Queen Sinaide is especially memorable in her highly emotionally charged scene, and in the title role the venerable Ruggero Raimondi at 74, amazingly enough can still sing the role although his voice is somewhat compromised by now. The young Italian conductor Francesco Quattrocchi, well attuned to the Rossini idiom, brings out beautiful sounds and sonorities. All in all the opera is severely truncated, but still an impressive, visually resplendent show for this special occasion.