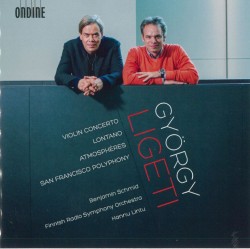

Ligeti – Violin Concerto; Lontano; Atmosphères; San Francisco Polyphony

Ligeti – Violin Concerto; Lontano; Atmosphères; San Francisco Polyphony

Ligeti – Violin Concerto; Lontano; Atmosphères; San Francisco Polyphony

Benjamin Schmid; Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra; Hannu Lintu

Ondine ODE 1213-2

It’s not just the terrific performances on this disc that make it so appealing. The programming of four iconic works by Hungarian composer György Ligeti offers a handy overview of the orchestral music of one of the most imaginative, idiosyncratic, influential and enjoyable composers of the past century. Ligeti was a loner, but his music was embraced by leading avant-garde composers and featured in popular films like 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The big draw here is violinist Benjamin Schmid’s energized performance of the majestic Violin Concerto, a late work from 1993. There are plenty of thrills, especially in the virtuosic cadenza. But what makes this performance so memorable is the way Schmid and conductor Hannu Lintu find the ideal balance between Ligeti’s angular modernism and his heartfelt lyricism.

The earliest work here, Atmosphères, from 1961, still fascinates – that such an apparently static work can be so gripping. The surface is all glassy smoothness. But Lintu takes us deep into the colours and textures swirling underneath as they emerge and recede.

By the time Ligeti wrote San Francisco Polyphony, in 1974, he was working with recognizable melodies, layering them in new and exciting ways. In his delightfully idiosyncratic booklet notes Lintu admits that “successfully executing the trickiest sequences in San Francisco Polyphony requires not only skill but a generous helping of good luck, too.” It sounds like everyone involved in this marvellous disc had plenty of both good luck and skill.

Concert note: Hannu Lintu conducts the Toronto Symphony Orchestra at Roy Thomson Hall on March 20 and 22 in Solen by Matthew Whittall, Symphony No.5 by Sibelius and Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.5, with Angela Hewitt as soloist.