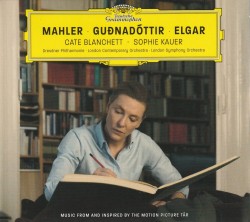

Mahler | Guđnadóttir | Elgar – Music from and inspired by the Motion Picture Tár

Mahler | Guđnadóttir | Elgar – Music from and inspired by the Motion Picture Tár

Cate Blanchett; Sophie Kauer; Dresdner Philharmonie; London Contemporary Orchestra; London Symphony Orchestra

Deutsche Grammophon 486 3431 (deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/tar-hildur-gunadottir-12805)

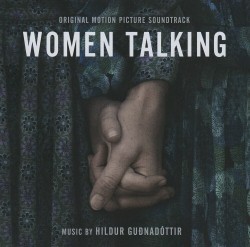

Hildur Guđnadóttir – Women Talking

Various Artists

Decca B0037031-02 (shop.decca.com/artist.html?a=hildur_gudnadottir)

Listening to and critiquing music written for film – in other words, a “soundtrack-only” compact disc – especially without having seen the film(s) in question – comes with not insignificant challenges. This is something score composers and film directors think about; certainly directors Todd Field (Tár) and Sarah Polley (Women Talking), and Hildur Guđnadóttir (who is credited with composing both soundtracks). Why, even eager record labels think about this. Field knows this all too well and alludes to it in his booklet notes for Tár, positing that listening to the music for the film without having it seen it can, indeed, be an altogether unforgettable experience: “Simply sit back and listen to the wonderful artistry on these tracks” he beckons. For the record, Polley hasn’t offered an opinion on booklet notes to the disc relating to Women Talking, but it is highly unlikely that she would disagree.

Moreover, it is difficult enough to compose music; to put together a truly great soundtrack for one film, let alone two. However, the inimitable Icelandic composer Guđnadóttir has done just that. Leonard Bernstein, who would know what composing for film was like, once used the words: “most awesome” to describe a celebrated effort by Igor Stravinsky for the film Oedipus Rex. He might have handed down the same judgement for Guđnadóttir’s too, for she has succeeded in conveying astute ideas and observations about humanity with exacting drama and in truth I, for one, would go further and suggest that this is exactly what Aristotle demanded of art and artists in his Poetics: he regarded this exact kind of artistic integrity as a model of formal dramatic perfection. Guđnadóttir’s soundtracks bring out that (Aristotelian) truth of both films with uncommon perfection.

In the case of the soundtrack for Tár, riveting drama is maintained throughout, thanks to snippets of dialogue from the film that are interspersed with the music. This is enhanced by cutting into a musical sequence, or better still, taking Cate Blanchett’s dialogue relating to musical direction during rehearsals and overlaying it on the score – particularly poignant in the rehearsals of Mahler’s Symphony No.5 in C-sharp Minor. This device is also repeated to great effect in the recording of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E Minor Op.85. The use of this during poignant bits of dallying, repeated phrases in the Largo movement of Tár is similarly affecting.

Meanwhile, for ardent lovers of the cello, the genius of the young cellist, Sophie Kauer shines bright everywhere, suggesting that she could hold court with the finest – Misha Maisky, Yo-Yo Ma, Steven Isserlis and Jacqueline du Pré, notwithstanding the fact Du Pré’s high watermark recording of the Elgar occupies so prominent a place (in cello literature and) on this recording. Kauer’s dolorous lines in the performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 is further proof of her prodigious craft. And then there are the choice bits of Blanchett (as actor) during the Bach piece and Elisa Vargas Fernandez’s beautifully forlorn Cura Mente. I could go on ad infinitum.

The ingenuity of Guđnadóttir’s score for Polley’s film Women Talking is of quite another kind. Here the composer uses a more contemporary musical vernacular – enhanced by a sweeping colour palette – to alternatively darken and brighten the despair contained within the film. For instance, Guđnadóttir makes particularly emotional use of the radiant sound of bells, contrasting this with the lonesome sound of pizzicato guitar lines. This music provides us with a sense of time and place, and setting for the unfolding drama, just as (once again) the use of a desolate sounding cello takes us to a place of loneliness and foreboding.

The ingenuity of Guđnadóttir’s score for Polley’s film Women Talking is of quite another kind. Here the composer uses a more contemporary musical vernacular – enhanced by a sweeping colour palette – to alternatively darken and brighten the despair contained within the film. For instance, Guđnadóttir makes particularly emotional use of the radiant sound of bells, contrasting this with the lonesome sound of pizzicato guitar lines. This music provides us with a sense of time and place, and setting for the unfolding drama, just as (once again) the use of a desolate sounding cello takes us to a place of loneliness and foreboding.

Clearly the challenge here is not only to provide colour and context in cinematic proportions, but in two or three minutes – or sometimes in mere seconds – to express a nuanced mood or emotion and to do it in a manner that is almost symphonically dramatic and trance-like. Guđnadóttir’s compositional style does all these things in both scores. Finally, both films are unmissable and so experiencing these soundtracks whilst watching them would almost certainly take you into whole new worlds. But that is quite another story.