Golden Dolden Box Set

Golden Dolden Box Set

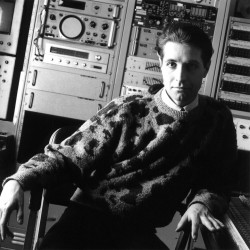

Paul Dolden

Independent (pauldolden.bandcamp.com)

In 1988 Canadian electroacoustic composer Paul Dolden (b.1956) started creating Below The Walls of Jericho – the first instalment of a three-part series that invoked the biblical story of Jericho, whose walls crumbled from the sheer power of sound. Though a number of Dolden’s earlier pieces – notably Veils (1984-5) – also employed multi-layered swarms of studio-recorded acoustic instrumentation, this was his first work to display an explicit preoccupation with sonic excess. Many of Dolden’s ensuing pieces also exhibit varying degrees of fascination with loudness, density, and velocity – enough for detractors to label his music, brazen or over-the-top.

In 1988 Canadian electroacoustic composer Paul Dolden (b.1956) started creating Below The Walls of Jericho – the first instalment of a three-part series that invoked the biblical story of Jericho, whose walls crumbled from the sheer power of sound. Though a number of Dolden’s earlier pieces – notably Veils (1984-5) – also employed multi-layered swarms of studio-recorded acoustic instrumentation, this was his first work to display an explicit preoccupation with sonic excess. Many of Dolden’s ensuing pieces also exhibit varying degrees of fascination with loudness, density, and velocity – enough for detractors to label his music, brazen or over-the-top.

It might therefore seem fitting that his latest offering occupies a similarly massive scope. Golden Dolden, is a career-spanning digital compendium featuring ten hours of music (including seven unreleased works), 34 scores, six hours’ of lectures, and a generous serving of text. The virtual box-set’s reverse-chronological avalanche may indeed be overwhelming, but immersing oneself in it reveals the depth of Dolden’s vibrant, utterly singular vision. He does often favour thick, saturated textures comprised of hundreds upon hundreds of active layers, but this vast collection is full of contrast, contradiction, imagination, and, yes, beauty.

Even at its most claustrophobic (such as on the aforementioned Jericho series) his music’s prevailing drive seems more inquisitive than destructive. The composer’s liner notes may be dismissive of his early catalogue’s underlying nihilism or postmodern posturing, but the swirling microtonal maelstroms are always projected through a radiant sheen of awe and wonder.

Various philosophical inputs have motivated Dolden’s practice over the years – modernist innovation, then postmodern’s fusion and fragmentation, even his own peculiar brand of romanticism. Yet despite outward shifts in conceptual approach, Dolden’s work finds unity in its unquenchable and downright contagious curiosity about what music can do.

The foundational reality of his pieces is the “anything-is-possible” frame provided by recorded music as a medium. Within it, he deploys the tactility of acoustic instruments in imaginary ensemble settings, the scales of which are sufficiently gargantuan to obscure their instrumental make-up. This allows him to craft outlandishly colourful, but decidedly organic sonorities, while forging strange and unexpected connections between disparate musical realms. His meticulous superimposition of multiple temporal strata and tuning systems is equally deft. It’s a paradigm-busting approach that situates him in the lineage of Charles Ives’ orchestral collages and Conlon Nancarrow’s whimsical automation, alongside the late Noah Creshevsky’s “hyperrealism.”

Studio composition L’ivresse de la vitesse (1992-3) – once Dolden’s calling card – is almost cartoonish in its wayward juxtapositions of material. Maniacal cascades of endless choir magically dissolve into big-band bedlam as filaments of free-jazz skronk explode into time-smeared rock n’ roll. Its vivid conjuring of various genres may tie it superficially to postmodernism, but its formal fluidity, giddy potency and conspicuous lack of irony steer its panoply of references somewhere unfamiliar.

According to Dolden, Entropic Twilights (1998-2000) refutes the notion that “the postmodern world is drained of substance, meaning, value and difference,” occupying a buoyant soundworld where unabashed prettiness wraps itself around precarious hair-pin turns. The shimmering 36-minute suite slithers between sonic spaces that variously resemble psychedelic orchestral music, agitated new age, jazz fusion and even metal. Yet these dramatic textural transformations never feel at all contrived. Where other composers have employed such adjacencies for their perverse humour, Dolden’s approach is almost stranger. It’s audible that these relationships exist on a profoundly visceral and sincere level for him.

In one of his essays, Dolden explains that “as a creator who learned from recordings and books, I could not afford to establish borders for acceptable musical behaviour.” His immersion in DIY experimentation since his teens is clearly one of the biggest determining factors behind his unorthodox sensibility. Though uncommon amongst peers of his own age, this trait aligns him with younger composers whose creative journeys began with recording technology.

The theme of transcendence runs throughout Dolden’s output but has become more central within the past two decades. He’s harvested musical data from the natural world. His longstanding respect for many global traditions has led him to embrace a multi-ethnic instrumentarium whilst eschewing appropriative superficiality. Works such as Memorizing the Sublime (2018-19) and 2020’s Moments for a Vibrating Universe also carve out what seem to be regions for simultaneous contemplation and perplexity – passages whose evocative power matches their utter inscrutability.

This distinctive liminal realm – far more than his much-touted sonic ferocity – may be the true essence of Dolden’s idiosyncratic universe – even a younger, edgier Dolden might agree. As he said in 1993, “An art work fascinates by its esotericism which preserves it from external logic.”