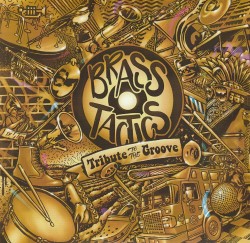

Tribute to the Groove - Brasstactics

Tribute to the Groove

Tribute to the Groove

Brasstactics

Independent (thebrasstactics.com)

Brasstactics bring the heat and punchy rhythms on their newest release, perfect for these end-of-summer, scorching days. Known for their complex rhythms, soaring horn melodies and driving bass lines, the group has been deemed “Edmonton’s premier party brass band.” The record has a lineup of both fiery original tunes penned by members of the group, as well as dance-worthy covers of popular songs, such as Bad Guy by Billie Eilish and Runaway Baby by Bruno Mars. Of course, a great album like this wouldn’t be possible without fantastic musicians, something this record definitely isn’t lacking, with renowned names like Audrey Ochoa on trombone, Jonny McCormack on tenor saxophone and Allison Ochoa on baritone saxophone. If you’re into the heavy brass-driven sound heard from the likes of the Heavyweights Brass Band, this is an album for you.

The energy that runs throughout each of these tunes is captivating and puts the listener in a good mood, no matter what kind of day you’re having. Take the aforementioned cover of Bad Guy for example: featuring a continuously raunchy bass melody and dynamic rhythm section, overlayed by flighty trumpet and trombone lines, the listener is immediately drawn along on a fun, lively musical ride. Their own compositions don’t fall short either; Dutch Angles sets the tone for an album of perfect, feel-good music with its groovy saxophone melodies and never-ending, hypnotizing beats.