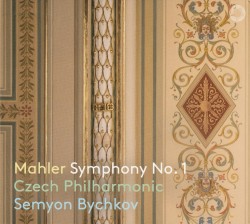

Mahler: Symphony No.1 - Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Semyon Bychkov

Mahler – Symphony No.1

Mahler – Symphony No.1

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Semyon Bychkov

Pentatone PTC 5187 043 (pentatonemusic.com/product/mahler-symphony-no-1)

Roll over Beethoven – you have been supplanted! And Gustav Mahler saw it coming. He is reputed to have proclaimed that “In 30 or 40 years Beethoven’s symphonies will no longer be played in concerts. My symphonies will take their place.” Well, it took a little longer than that, only really gaining steam in the 1960s, but judging from the number of Mahler cycles issued these days his time has truly come.

This new release of Mahler’s first and arguably most popular symphony performed by the distinguished Czech Philharmonic represents the fourth instalment of Semyon Bychkov’s traversal of these mighty works. Though he eventually abandoned any programmatic descriptions of his compositions, as late as 1893 Mahler still felt compelled to describe his first symphony as “a tone poem in the form of a symphony.” More importantly, he defined the work as consisting of two over-arching sections. The first included the first three movements (the third movement was eventually dropped) while the second encompassed the final two movements. The first part most closely resembles the traditional symphonic genre, and it is here that Bychkov adopts a fairly conventional approach, straightforward, pellucid and artfully nuanced. The second section, subtitled Commedia Humana, completely baffled the audience at the Budapest premiere and was not well received. It seems that the promoters neglected to supply the audience with the guidance of program notes… (As an aside, I’ve often wondered how any audience could be expected to follow the convoluted plots of such works as Richard Strauss’ Alpine Symphony. No wonder Mahler abandoned them.)

No matter though; the excellent liner notes by Gavin Plumley will tell you all you need to know, and more. From the opening funeral march of part two onwards, Bychkov and the orchestra gradually pull out all the stops in a masterful crescendo of emotion. The finale in particular has the uncanny effect of the whole of one’s life passing before one’s eyes through a near-death experience that resolves itself in a shatteringly triumphant affirmation of life. I for one found it deeply moving.

The wide-ranging sound of this elegant orchestra is superbly rendered by the expert team at Pentatone Records. A must-have recording indeed.