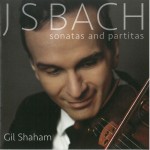

Gil Shaham has long been one of my favourite violinists, the grace, intelligence and warmth of his playing never failing to produce performances of the highest quality. I opened his latest release, a 2CD set of the Bach Sonatas and Partitas on his own Canary Classics label (CC14), expecting great things, and I wasn’t disappointed. Because of the great challenges they present, many players are in no rush to commit the Bach solo works to disc; in Shaham’s case he didn’t even start performing them in public until about ten years ago. His continuing exploration of the music led him to experiment with wound gut strings and a baroque-style bridge and bow in an effort to more closely reproduce the sound of Bach’s own violin. For this current recording Shaham started with a more modern set-up, tried both approaches and eventually settled for the baroque option; it’s a great choice, with the warm, bright sound a perfect match for his style, and the lighter baroque bow in particular allowing for much cleaner passagework in Shaham’s decidedly faster tempos. There’s never a sense of rushing, though; the multiple stopping is always clean, the melodic line always clear, and Shaham often uses a brief rubato to allow the music to breathe or to highlight phrase peaks. His approach to the sometimes thorny issue of vibrato in baroque music is a decidedly sensible compromise: “I use some vibrato, but I try to err on the side of not using too much.”

Gil Shaham has long been one of my favourite violinists, the grace, intelligence and warmth of his playing never failing to produce performances of the highest quality. I opened his latest release, a 2CD set of the Bach Sonatas and Partitas on his own Canary Classics label (CC14), expecting great things, and I wasn’t disappointed. Because of the great challenges they present, many players are in no rush to commit the Bach solo works to disc; in Shaham’s case he didn’t even start performing them in public until about ten years ago. His continuing exploration of the music led him to experiment with wound gut strings and a baroque-style bridge and bow in an effort to more closely reproduce the sound of Bach’s own violin. For this current recording Shaham started with a more modern set-up, tried both approaches and eventually settled for the baroque option; it’s a great choice, with the warm, bright sound a perfect match for his style, and the lighter baroque bow in particular allowing for much cleaner passagework in Shaham’s decidedly faster tempos. There’s never a sense of rushing, though; the multiple stopping is always clean, the melodic line always clear, and Shaham often uses a brief rubato to allow the music to breathe or to highlight phrase peaks. His approach to the sometimes thorny issue of vibrato in baroque music is a decidedly sensible compromise: “I use some vibrato, but I try to err on the side of not using too much.”

It doesn’t always happen that you can put on a CD of the Sonatas and Partitas and just let it play; quite often there’s a gravity or seriousness to the performance that makes playing right through all six works quite demanding listening. Not with Shaham, though; he creates a world of warmth and light, and each of the two CDs just flies past. The playing here is light and brilliant without ever being superficial; fast without ever losing the sense of phrase; joyous and spontaneous without ever losing a sense of emotional depth; gentle but never weak; and strong but never strident.

There’s a great deal of competition in recordings of the Bach solo works, of course, with a wide range of styles and approaches to choose from, but you’ll go a long way before you find a more beautiful and satisfying set than this.

There’s another outstanding set of Bach solo works this month, this time the Cello Suites featuring the German cellist Isang Enders (Berlin Classics 0300552BC). The similarities with the Shaham set are quite striking: the 28-year-old Enders says that Bach has been in his life since early childhood, and that the challenges presented by the Cello Suites made him constantly doubt his abilities when it came to recording them. Then, after his first attempt had gone through the final production stages, he rejected it and returned to the studio to do justice not only to his own developing thoughts about the music but also “to do justice to Bach himself.”

There’s another outstanding set of Bach solo works this month, this time the Cello Suites featuring the German cellist Isang Enders (Berlin Classics 0300552BC). The similarities with the Shaham set are quite striking: the 28-year-old Enders says that Bach has been in his life since early childhood, and that the challenges presented by the Cello Suites made him constantly doubt his abilities when it came to recording them. Then, after his first attempt had gone through the final production stages, he rejected it and returned to the studio to do justice not only to his own developing thoughts about the music but also “to do justice to Bach himself.”

Above all, he addresses the discussion about “historically informed,” as opposed to historical, performance practices that has been ever-present for players of his generation; his quoting of Nikolaus Harnoncourt in this regard (“words that say it all for me”) is worth repeating: “We naturally need to acquaint ourselves with performance practice, but let us not retreat into false purism, into false objectivity, into misinterpreted fidelity to the original. So I beg of you: do not be afraid of vibrato, liveliness or subjectivity, but do be very afraid of coldness, purism, ‘objectivity’ and barren historicism.”

Not only could that be a perfect guide for Shaham’s approach, but Enders also certainly takes this to heart: there is warmth and brightness to his playing and a real liveliness, especially in the dance movements where – as with Shaham – a judicial use of rubato helps to shape the phrases. For the two discs, Enders divides the suites into what he sees as light and dark colours, although he doesn’t really elucidate: Suites 5, 2 and 4 (in C minor, D minor and E flat major) on CD1 bring out the interval of a rising second, while Suites 3, 1 and 6 (in C, G and D major) on CD2 are keys in the circle of fifths. Whether or not that sequence contributes to the overall effect is irrelevant; all that matters is that, like the Shaham, this is a set that can more than hold its own against strong competition, and it’s as enjoyable a cello performance of these Suites as I have heard.

If you’re interested in contemporary cello music then you’ll certainly want to check out Crossings: New Music for Cello, a new CD featuring the American cellist Kate Dillingham and pianist Amir Khosrowpour (furious artisans FACD 6815). Expenses for the recording, which Dillingham calls a CD of cutting-edge contemporary compositions, were raised through the online crowdfunding platform RocketHub. Dillingham’s description of the music will give you a good idea of what to expect: “The musical expression varies widely: from driving rhythms to expansive, contemplative phrases; long, lyrical lines to in-your-face badass riffs; simple musical statements to bow hair-shredding technical challenges!”

If you’re interested in contemporary cello music then you’ll certainly want to check out Crossings: New Music for Cello, a new CD featuring the American cellist Kate Dillingham and pianist Amir Khosrowpour (furious artisans FACD 6815). Expenses for the recording, which Dillingham calls a CD of cutting-edge contemporary compositions, were raised through the online crowdfunding platform RocketHub. Dillingham’s description of the music will give you a good idea of what to expect: “The musical expression varies widely: from driving rhythms to expansive, contemplative phrases; long, lyrical lines to in-your-face badass riffs; simple musical statements to bow hair-shredding technical challenges!”

American composers represented here are Gilbert Galindo, David Fetherolf, Gabriela Lena Frank, B. Allen Schulz and Jonathan Pieslak, although the four composers born outside the U.S.A. – Jorge Muñiz, Yuan-Chen Li, Federico Garcia-De Castro and Wang Jie – are all currently active in the American music scene.

The CD booklet includes bios of all the composers, but unfortunately not a word about the music – when and how it came to be written, for instance – although it’s clear from Dillingham’s comments on the RocketHub site that she works closely with most of the composers represented here, particularly those belonging to the composer collectives in New York (Random Access Music) and Pittsburgh (Alia Musica).

Four of the pieces are for solo cello and five for cello and piano. It’s difficult to make any meaningful comments about such a variety of recent pieces, but they are all clearly quite strong, colourful compositions that make an immediate impact; no single work here seems out of place. Both performers are more than up to the challenges – and believe me, there are quite a few!

With a playing time of almost 80 minutes it’s a fascinating portrait of contemporary American cello music. Watch the eight-minute Crossings Documentary on YouTube for background information on the making of the CD; there are also short clips of Gilbert Galindo and Federico Garcia-De Castro discussing their compositions.

Myth, the latest CD from the young Dutch violinist Rosanne Philippens, features the music of Polish composer Karol Szymanowski and it’s outstanding (Channel Classics CCS SA 36715). The main work here is the Violin Concerto No.1 Op.35 from 1916, with Xian Zhang conducting the NJO (the National Youth Orchestra of the Netherlands). It’s a beautifully lyrical work in one movement with a glorious rhapsodic main theme, and was written for the Polish violinist Pawel Kochański, who contributed significantly to the solo part and also wrote the cadenza. A good deal of the violin part is up in the stratosphere and requires not only a brilliant, shimmering tone but a rock-solid technical assurance. Philippens has both in abundance. She also clearly has a feel for Szymanowski’s music, having been introduced to the three-movement Myths, Op.30 a few years ago by the pianist Julien Quentin, who joins her for the rest of the CD. Myths, from 1915, was also written for Kochański, and has a distinctly Impressionist feel to it.

Myth, the latest CD from the young Dutch violinist Rosanne Philippens, features the music of Polish composer Karol Szymanowski and it’s outstanding (Channel Classics CCS SA 36715). The main work here is the Violin Concerto No.1 Op.35 from 1916, with Xian Zhang conducting the NJO (the National Youth Orchestra of the Netherlands). It’s a beautifully lyrical work in one movement with a glorious rhapsodic main theme, and was written for the Polish violinist Pawel Kochański, who contributed significantly to the solo part and also wrote the cadenza. A good deal of the violin part is up in the stratosphere and requires not only a brilliant, shimmering tone but a rock-solid technical assurance. Philippens has both in abundance. She also clearly has a feel for Szymanowski’s music, having been introduced to the three-movement Myths, Op.30 a few years ago by the pianist Julien Quentin, who joins her for the rest of the CD. Myths, from 1915, was also written for Kochański, and has a distinctly Impressionist feel to it.

Other Szymanowski works presented here are the beautiful Chant de Roxane (an arrangement of an aria from the opera Krol Roger), and the Nocturne and Tarantella Op.28, also from 1915. Again, Philippens displays a brilliant tone and flawless technique in some really difficult music. Szymanowski was influenced by the music of Igor Stravinsky, who was exerting his own influence on the musical world in the years before the Great War, and three short works by the latter complete the CD. Stravinsky’s Firebird was a particular favourite of Szymanowski, and Philippens extends the “Myth” concept to include the Berceuse and Scherzo from the ballet, as well as the later Chanson Russe.

This really is an outstanding CD, full of dazzling playing from a violinist with a strong musical intellect. If you haven’t heard Rosanne Philippens yet, don’t worry – it won’t be long before you do.

The Romanian George Enescu, who died in 1955, was arguably the last of the great violinist/composers. Volume 2 of his Complete Works for Violin and Piano has just been released by Naxos (8.572692), and like Volume 1 (Naxos 8.572691) features the terrific German violinist Axel Strauss and the Russian pianist Ilya Poletaev, both of whom are currently on the faculty at the Schulich School of Music at McGill University.

The Romanian George Enescu, who died in 1955, was arguably the last of the great violinist/composers. Volume 2 of his Complete Works for Violin and Piano has just been released by Naxos (8.572692), and like Volume 1 (Naxos 8.572691) features the terrific German violinist Axel Strauss and the Russian pianist Ilya Poletaev, both of whom are currently on the faculty at the Schulich School of Music at McGill University.

The Violin Sonata No.1 was written in 1897 when Enescu was only 16 years old, and although it leans heavily on the German sonata tradition – especially Brahms – it is a very strong work that draws some outstanding playing from both performers. Two shorter pieces pre-date the sonata: the Ballade Op.4a was originally for violin and orchestra; and the unpublished Tarantella provides ample evidence of Enescu’s technical ability in his teenage years. The Aubade is a 1903 violin and piano version of a short piece written for string trio in 1899. The Hora Unirii from 1917 and the relatively late Andantino malinconico from 1951 complete the selection of effective and attractive shorter pieces. But the real gem on this CD is the Impressions d’enfance Op.28 from 1940, an astonishing suite-like work of ten short movements, played mostly without a break, which traces the day in the life of a child. There’s a folk fiddler, a stream in the garden, a caged bird and a cuckoo clock, a chirping cricket, the moon shining through the window, the howling of the wind in the chimney (a ghostly 23 seconds of scratchy violin solo) and a distant thunder storm at night. In the booklet notes, Poletaev calls the work “…a stupendous compositional tour-de-force… a musical fabric of extraordinary sophistication and richness.” It certainly is, and it’s worth the price of an exceptional CD on its own.

I didn’t know exactly what to expect from Partita for Solo Violin: Tim Fain Plays Philip Glass (Orange Mountain Music OMM 0050), but what I heard was a revelation. Glass, recently named as laureate of the Glenn Gould Prize, has been a prolific and immensely influential composer for the past 50 years or so, with a far greater range of compositions than the familiar description of him as a “minimalist” would suggest; Glass himself has always disliked that term, feeling that he moved away from the style years ago, and now considers himself a “classicist.” Even so, I wasn’t prepared for such an incredibly strong, idiomatic solo violin work in a very traditional style (Opening; Morning Song; Dance 1; Chaconne Part 1; Dance 2; Evening Song; Chaconne Part 2) which quite clearly pays homage to the Bach Sonatas & Partitas; it’s a towering and powerful composition, strongly tonal and with a wide emotional, technical and dynamic range.

I didn’t know exactly what to expect from Partita for Solo Violin: Tim Fain Plays Philip Glass (Orange Mountain Music OMM 0050), but what I heard was a revelation. Glass, recently named as laureate of the Glenn Gould Prize, has been a prolific and immensely influential composer for the past 50 years or so, with a far greater range of compositions than the familiar description of him as a “minimalist” would suggest; Glass himself has always disliked that term, feeling that he moved away from the style years ago, and now considers himself a “classicist.” Even so, I wasn’t prepared for such an incredibly strong, idiomatic solo violin work in a very traditional style (Opening; Morning Song; Dance 1; Chaconne Part 1; Dance 2; Evening Song; Chaconne Part 2) which quite clearly pays homage to the Bach Sonatas & Partitas; it’s a towering and powerful composition, strongly tonal and with a wide emotional, technical and dynamic range.

Tim Fain’s outstanding performance is definitive; the Partita is the central work in the recitals that Fain and Glass regularly perform together. There is no CD booklet, so no information on the work’s genesis, but Fain has been collaborating closely with Glass since 2008, when he had a short featured solo in the Book of Longing, Glass’s setting of poems by Leonard Cohen; their enjoying working together led to the writing of the Partita for Fain in 2011.

Three short works complete the CD. Knee 2 from the opera Einstein on the Beach is more what you might expect from Glass – a helter-skelter perpetuum mobile with slight shifts and changes in the patterns and accents. Book of Longing is the solo mentioned above; the contemplative Interludes from the Violin Concerto No.2 bring a marvellous CD to a close.

Fratres is the new CD from ATMA celebrating 30 years of the Quebec chamber orchestra Les Violons du Roy, founded in 1984 by conductor Bernard Labadie (ACD2 3015). Over the years the group has released close to 30 CDs, mostly on the Dorian, Virgin Classics, Naïve, Hyperion, Erato and Analekta labels; since 2004 there have been eight CDs on the Quebec ATMA label, and it is from that catalogue that this self-styled compilation sampler has been put together. Sampler CDs, with their mixture of single extracted movements and short complete pieces, can tend to be less than satisfying in some respects, but the very high performance standards here together with the lovely recording quality and the choice of titles makes this a very attractive release.

Fratres is the new CD from ATMA celebrating 30 years of the Quebec chamber orchestra Les Violons du Roy, founded in 1984 by conductor Bernard Labadie (ACD2 3015). Over the years the group has released close to 30 CDs, mostly on the Dorian, Virgin Classics, Naïve, Hyperion, Erato and Analekta labels; since 2004 there have been eight CDs on the Quebec ATMA label, and it is from that catalogue that this self-styled compilation sampler has been put together. Sampler CDs, with their mixture of single extracted movements and short complete pieces, can tend to be less than satisfying in some respects, but the very high performance standards here together with the lovely recording quality and the choice of titles makes this a very attractive release.

The title track is a previously unreleased 2008 recording of the Arvo Pärt composition, featuring violinist Pascale Giguère. There’s a beautiful performance of the Mozart concert aria Chi’ omi scordi di te? by soprano Karina Gauvin, who is also featured in a performance of Britten’s Now sleeps the crimson petal and – along with countertenor Daniel Taylor – in an extract from Bach’s Tilge, Hochster, meine Sünden. There’s a movement from Bartók’s Divertimento, Gluck’s Ballet des Ombres heureuses, Mozart’s Overture to Lucio Silla, Handel’s Arrival of the Queen of Sheba, a brief Rameau piece and Astor Piazzolla’s Milonga del Angel. Oh – and the Pachelbel Canon. Bet you weren’t expecting that. Labadie conducts most of the tracks; Jean-Marie Zeitouni conducts all but one of the remaining five.

Also from ATMA, the third and final volume of the outstanding complete cycle of the Beethoven String Quartets by the Quatuor Alcan has just been released (ATMA ACD2 2493). It’s another 3CD set, and features the wonderful late quartets: Opp.127, 130, 131, 132, 133 (Grosse Fuge) and 135. The entire cycle was recorded between May 2008 and December 2012 but, as noted earlier, the fact that all the recordings were made in the excellent acoustics of the Salle Françoys-Bernier at Le Domaine Forget in Saint-Irénée, Quebec means that there is no discernable difference in the recorded sound. There is also no discernable difference in the uniformly high standard of the performances. It really is a terrific set from a terrific ensemble, and a fitting celebration of their 25th anniversary.

Also from ATMA, the third and final volume of the outstanding complete cycle of the Beethoven String Quartets by the Quatuor Alcan has just been released (ATMA ACD2 2493). It’s another 3CD set, and features the wonderful late quartets: Opp.127, 130, 131, 132, 133 (Grosse Fuge) and 135. The entire cycle was recorded between May 2008 and December 2012 but, as noted earlier, the fact that all the recordings were made in the excellent acoustics of the Salle Françoys-Bernier at Le Domaine Forget in Saint-Irénée, Quebec means that there is no discernable difference in the recorded sound. There is also no discernable difference in the uniformly high standard of the performances. It really is a terrific set from a terrific ensemble, and a fitting celebration of their 25th anniversary.

Stradivari’s Gift, for Narrator, Violin and String Orchestra, is one of two story-and-music CDs (Amati’s Dream is the other) that will take young listeners on a journey to the violin workshops of 17th-century Cremona (Atlantic Crossing Records ACR 0001). The story and music are by the American author and composer Kim Maerkl, who founded Atlantic Crossing Records, and the violin soloist is her husband Key-Thomas Maerkl; the English actor Sir Roger Moore is the narrator.

Stradivari’s Gift, for Narrator, Violin and String Orchestra, is one of two story-and-music CDs (Amati’s Dream is the other) that will take young listeners on a journey to the violin workshops of 17th-century Cremona (Atlantic Crossing Records ACR 0001). The story and music are by the American author and composer Kim Maerkl, who founded Atlantic Crossing Records, and the violin soloist is her husband Key-Thomas Maerkl; the English actor Sir Roger Moore is the narrator.

The Maerkls hope that the CDs will inspire children to further explore classical music, and their creation here is first class, in much the same style as the well-known Classical Kids series of story-and-music CDs and DVDs. The story is simple, the music clear and uncomplicated but quite beautiful, and the performance of the violin solo part is simply stunning. Although the CD refers to “an original score for violin and string orchestra” all the supporting music here – string orchestra, guitar and harp effects – appears to have been produced on a keyboard synthesizer; it certainly doesn’t diminish the effect of the CD, though.

The story deals with the loss of court violinist Raphael’s Amati violin and its replacement with a violin made for him by Stradivari, and is long enough to be interesting but short enough – at just under 37 minutes – to hold a young person’s attention. Quite appropriately, Key Maerkl performs the solo violin part on a Stradivarius violin made in 1692 – and what a glorious sound it is!

Incidentally, if you’re a bit confused by the dual use of the names Stradivari and Stradivarius when discussing the maker and his instruments, here’s the explanation: the maker’s Italian name was Antonio Stradivari, but the labels he used in his violins were in Latin, showing Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis Faciebat (made in Cremona by Antonio Stradivari). As a result, an instrument of his is usually known as a Stradivarius, but Stradivari is the correct form for the maker’s name.

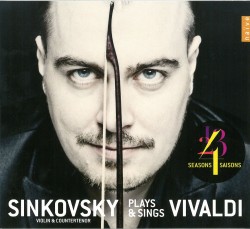

Sinkovsky Plays & Sings Vivaldi

Sinkovsky Plays & Sings Vivaldi