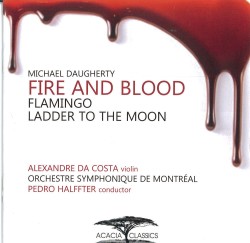

The Montreal violinist Alexandre Da Costa is back with another outstanding CD of contemporary works, this time with the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal under Pedro Halffter in Fire and Blood, featuring the music of the American composer Michael Daugherty (Acacia Classics ACA 2 0931). The title work is a violin concerto from 2003; commissioned by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, it was inspired by the “Detroit Industry” murals at the Detroit Institute of Art, painted in the early 1930s by the Mexican artist Diego Rivera on a commission from Edsel Ford. The opening movement – “Volcano” – invokes the fires of Mexican volcanoes and the blaze of factory furnaces. The beautiful second movement – “River Rouge” – is named for the Ford complex where Rivera spent several months sketching with his wife, artist Frida Kahlo; her long-term serious health problems – she almost died from a miscarriage while in Detroit with her husband – resulted in “the color of blood” being everywhere in her works of that period. The third movement – “Assembly Line” – is described by the composer as “a roller coaster ride on a conveyor belt,” with the violin representing the worker surrounded by a mechanical and metallic orchestra that includes a ratchet and brake drums! It’s stunning stuff with wonderful orchestration. It’s difficult to imagine it being performed any better. Two shorter works complete the CD: Flamingo, for two tambourines and orchestra; and Ladder to the Moon, for violin, wind octet, double bass and percussion. Da Costa is again outstanding in the latter, a two-movement work also inspired by art – this time a musical tribute to Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1925-30 paintings of New York skyscrapers and the Manhattan cityscape.

The Montreal violinist Alexandre Da Costa is back with another outstanding CD of contemporary works, this time with the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal under Pedro Halffter in Fire and Blood, featuring the music of the American composer Michael Daugherty (Acacia Classics ACA 2 0931). The title work is a violin concerto from 2003; commissioned by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, it was inspired by the “Detroit Industry” murals at the Detroit Institute of Art, painted in the early 1930s by the Mexican artist Diego Rivera on a commission from Edsel Ford. The opening movement – “Volcano” – invokes the fires of Mexican volcanoes and the blaze of factory furnaces. The beautiful second movement – “River Rouge” – is named for the Ford complex where Rivera spent several months sketching with his wife, artist Frida Kahlo; her long-term serious health problems – she almost died from a miscarriage while in Detroit with her husband – resulted in “the color of blood” being everywhere in her works of that period. The third movement – “Assembly Line” – is described by the composer as “a roller coaster ride on a conveyor belt,” with the violin representing the worker surrounded by a mechanical and metallic orchestra that includes a ratchet and brake drums! It’s stunning stuff with wonderful orchestration. It’s difficult to imagine it being performed any better. Two shorter works complete the CD: Flamingo, for two tambourines and orchestra; and Ladder to the Moon, for violin, wind octet, double bass and percussion. Da Costa is again outstanding in the latter, a two-movement work also inspired by art – this time a musical tribute to Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1925-30 paintings of New York skyscrapers and the Manhattan cityscape.

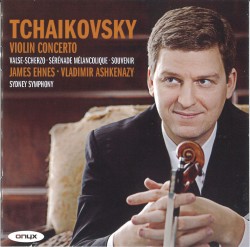

The latest CD from Canada’s James Ehnes sees him paired with the Sydney Symphony and Vladimir Ashkenazy in an all-Tchaikovsky programme recorded live at Australia’s Sydney Opera House in December 2010 (ONYX 4076). I was lucky enough to catch this same team in a memorable performance of the Elgar violin concerto in Sydney in 2009, and it’s no surprise to find them continuing their relationship. Ashkenazy was also the conductor for the Ehnes CD of the Mendelssohn concerto in 2010. The Violin Concerto is obviously the main work here, and it’s a terrific performance, with Ashkenazy drawing idiomatic playing from the orchestra, and Ehnes always managing to find something fresh to say in the solo part while making the technical difficulties sound easy. The two other works with orchestra, the Sérénade mélancolique Op.26, and the Valse-scherzo Op.34, receive equally compelling performances from all concerned.

The latest CD from Canada’s James Ehnes sees him paired with the Sydney Symphony and Vladimir Ashkenazy in an all-Tchaikovsky programme recorded live at Australia’s Sydney Opera House in December 2010 (ONYX 4076). I was lucky enough to catch this same team in a memorable performance of the Elgar violin concerto in Sydney in 2009, and it’s no surprise to find them continuing their relationship. Ashkenazy was also the conductor for the Ehnes CD of the Mendelssohn concerto in 2010. The Violin Concerto is obviously the main work here, and it’s a terrific performance, with Ashkenazy drawing idiomatic playing from the orchestra, and Ehnes always managing to find something fresh to say in the solo part while making the technical difficulties sound easy. The two other works with orchestra, the Sérénade mélancolique Op.26, and the Valse-scherzo Op.34, receive equally compelling performances from all concerned.

Ashkenazy returns to his first profession as pianist for the final work, accompanying Ehnes in the three-movement Souvenir d’un lieu cher Op.42. Again, the mutual understanding is there for all to hear. It’s another terrific addition to the already impressive Ehnes discography.

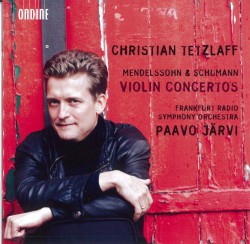

There are more live recordings featured on the latest CD from Christian Tetzlaff (ONDINE ODE 1195-2) which features the Violin Concertos of Mendelssohn and Schumann, with Paavo Järvi conducting the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra. Tetzlaff was artist in residence with the orchestra when the recordings were made in September 2008 and February 2009. The Mendelssohn is a beautiful performance, never over-played, with an affecting slow movement and a finale that displays detailed, subtle and sensitive playing without ever losing a sense of line. The Schumann concerto has had a troubled history and waited 84 years for its eventual premiere in 1937. The beautiful slow movement is its saving grace, but the opening movement material is not the greatest, and with its demanding technical difficulty it’s not hard to see why the concerto continues to struggle to enter the mainstream repertoire. Tetzlaff, however, does a lovely job with this work, as he does with the Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra, which was also written in 1853 and quickly fell out of favour. It was originally felt to be a brilliant and cheerful piece, but Schumann’s mental illness and death within three years seemed to change the public perception of the work. In this repertoire, though, Tetzlaff is up against stiff competition from Ulf Wallin, whose definitive performances of these works on the BIS label were reviewed in depth in the September 2011 Strings Attached column.

There are more live recordings featured on the latest CD from Christian Tetzlaff (ONDINE ODE 1195-2) which features the Violin Concertos of Mendelssohn and Schumann, with Paavo Järvi conducting the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra. Tetzlaff was artist in residence with the orchestra when the recordings were made in September 2008 and February 2009. The Mendelssohn is a beautiful performance, never over-played, with an affecting slow movement and a finale that displays detailed, subtle and sensitive playing without ever losing a sense of line. The Schumann concerto has had a troubled history and waited 84 years for its eventual premiere in 1937. The beautiful slow movement is its saving grace, but the opening movement material is not the greatest, and with its demanding technical difficulty it’s not hard to see why the concerto continues to struggle to enter the mainstream repertoire. Tetzlaff, however, does a lovely job with this work, as he does with the Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra, which was also written in 1853 and quickly fell out of favour. It was originally felt to be a brilliant and cheerful piece, but Schumann’s mental illness and death within three years seemed to change the public perception of the work. In this repertoire, though, Tetzlaff is up against stiff competition from Ulf Wallin, whose definitive performances of these works on the BIS label were reviewed in depth in the September 2011 Strings Attached column.

The Kernis Project: Beethoven is the title of a new CD from a young American ensemble, the Jasper String Quartet (Sono Luminus DSL-92142). It pairs the Beethoven Op.59, No.3 with the String Quartet No.2 “musica instrumentalis,” by American composer Aaron Jay Kernis, the last movement of which is based on the finale of the Beethoven quartet. The Jasper Quartet gives a full-blooded, committed reading of the Beethoven, but the real treasure here is the Kernis. The three-movement work, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1998, is an absolute stunner: deep, strong, rich,accessible. There are shades of Shostakovich in the slow movement, and the finale – “Double Triple Gigue Fugue (after Beethoven)” – is truly exhilarating. Although it wasn’t written for them, the Jasper Quartet comment that this was a work they connected with “right from the start.” It’s easy to hear why, and to share their connection. How reassuring – and what a thrill – to hear contemporary works that can hold their own against the classics.

The Kernis Project: Beethoven is the title of a new CD from a young American ensemble, the Jasper String Quartet (Sono Luminus DSL-92142). It pairs the Beethoven Op.59, No.3 with the String Quartet No.2 “musica instrumentalis,” by American composer Aaron Jay Kernis, the last movement of which is based on the finale of the Beethoven quartet. The Jasper Quartet gives a full-blooded, committed reading of the Beethoven, but the real treasure here is the Kernis. The three-movement work, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1998, is an absolute stunner: deep, strong, rich,accessible. There are shades of Shostakovich in the slow movement, and the finale – “Double Triple Gigue Fugue (after Beethoven)” – is truly exhilarating. Although it wasn’t written for them, the Jasper Quartet comment that this was a work they connected with “right from the start.” It’s easy to hear why, and to share their connection. How reassuring – and what a thrill – to hear contemporary works that can hold their own against the classics.

Kernis also turns up on River of Light – American Short Works for Violin and Piano, a new Naxos release in the superb American Classics series (Naxos 8.559662). The title is slightly misleading, as two of the works – Philip Glass’ “Knee Play 2” from Einstein on the Beach and Patrick Zimmerli’s three-movement The Light Guitar – are for violin solo. Virtually all of the works are by living composers and written within the last 35 years, the exception being the 1953 Wistful Piece by Ruth Shaw Wylie, who died in 1989. Lev Zhurbin’s Sicilienne, Jennifer Higdon’s Legacy, Zimmerli’s piece and Richard Danielpour’s title track River of Light are all world premiere recordings. The Kernis Air, Kevin Puts’ Aria and William Bolcom’s Graceful Ghost Rag complete a fascinating and predominantly lyrical programme. The American violinist Tim Fain, who was recently featured in the movie Black Swan, is in his element here, as much at home in the frenetic Glass piece as in the lyrical beauty of the Puts, Kernis and Zhurbin works. Fain grew up playing the standard 19thcentury short virtuoso pieces, and sees this CD as bringing the tradition into the present. Pianist Pei-Yao Wang is a perfect partner in music that is always thought-provoking and immensely satisfying, without ever resorting to the merely virtuosic.

Kernis also turns up on River of Light – American Short Works for Violin and Piano, a new Naxos release in the superb American Classics series (Naxos 8.559662). The title is slightly misleading, as two of the works – Philip Glass’ “Knee Play 2” from Einstein on the Beach and Patrick Zimmerli’s three-movement The Light Guitar – are for violin solo. Virtually all of the works are by living composers and written within the last 35 years, the exception being the 1953 Wistful Piece by Ruth Shaw Wylie, who died in 1989. Lev Zhurbin’s Sicilienne, Jennifer Higdon’s Legacy, Zimmerli’s piece and Richard Danielpour’s title track River of Light are all world premiere recordings. The Kernis Air, Kevin Puts’ Aria and William Bolcom’s Graceful Ghost Rag complete a fascinating and predominantly lyrical programme. The American violinist Tim Fain, who was recently featured in the movie Black Swan, is in his element here, as much at home in the frenetic Glass piece as in the lyrical beauty of the Puts, Kernis and Zhurbin works. Fain grew up playing the standard 19thcentury short virtuoso pieces, and sees this CD as bringing the tradition into the present. Pianist Pei-Yao Wang is a perfect partner in music that is always thought-provoking and immensely satisfying, without ever resorting to the merely virtuosic.

English viola music has already been well-served by the Naxos label, and now there’s a new CD featuring the Viola Sonatas Nos.1 and 2 and the Phantasy of Edwin York Bowen in performances by the Bridge Duo (Naxos 8.572580). York Bowen, born in 1884, was a prodigiously-gifted musician and an outstanding composer, but – as was the case with several other British composers – his style came to be considered outdated in the years following the Great War. Bowen worked closely with Lionel Tertis, the man who was almost single-handedly responsible for establishing the viola as a legitimate solo instrument: Tertis premiered Bowen’s Viola Concerto in 1908, as well as these two sonatas a few years earlier. Both sonatas, No.1 in C Minor and No.2 in F Major, date from 1905. They are marvellous works, quintessentially English and exhibiting great strength and variety. The single-movement Phantasy was written in 1918 and was Bowen’s entry in the annual W. W. Cobbett Phantasy composition competition that produced so many outstanding English works. Tertis saw no reason to treat writing for the viola any differently than writing for the violin and as a result all three works are technically very challenging, a fact that no doubt contributed to their somewhat sparse performance history until fairly recently. The Bridge Duo – violist Matthew Jones and pianist Michael Hampton – are fully up to the challenge in a beautifully-recorded disc that makes a fine companion to their recital of English Music for Viola (Naxos 8.572579).

English viola music has already been well-served by the Naxos label, and now there’s a new CD featuring the Viola Sonatas Nos.1 and 2 and the Phantasy of Edwin York Bowen in performances by the Bridge Duo (Naxos 8.572580). York Bowen, born in 1884, was a prodigiously-gifted musician and an outstanding composer, but – as was the case with several other British composers – his style came to be considered outdated in the years following the Great War. Bowen worked closely with Lionel Tertis, the man who was almost single-handedly responsible for establishing the viola as a legitimate solo instrument: Tertis premiered Bowen’s Viola Concerto in 1908, as well as these two sonatas a few years earlier. Both sonatas, No.1 in C Minor and No.2 in F Major, date from 1905. They are marvellous works, quintessentially English and exhibiting great strength and variety. The single-movement Phantasy was written in 1918 and was Bowen’s entry in the annual W. W. Cobbett Phantasy composition competition that produced so many outstanding English works. Tertis saw no reason to treat writing for the viola any differently than writing for the violin and as a result all three works are technically very challenging, a fact that no doubt contributed to their somewhat sparse performance history until fairly recently. The Bridge Duo – violist Matthew Jones and pianist Michael Hampton – are fully up to the challenge in a beautifully-recorded disc that makes a fine companion to their recital of English Music for Viola (Naxos 8.572579).

There is more viola music – again from a mostly overlooked composer and with another link to Tertis – on the CD of the Complete Works for Viola & Piano by Joseph Jongen (FUGA LIBERA FUG586). Jongen, born in 1873, was also a precociously-gifted musician, and met Tertis in London in 1914 after fleeing from occupied Belgium at the outbreak of the Great War. He also knew the great French viola player Maurice Vieux in the 1920s. Like Bowen, Jongen was a craftsman who produced works of the highest order, but whose reputation suffered as musical styles evolved through the middle of the 20th century. Both Tertis and Vieux were prominent in establishing the viola as a legitimate solo instrument, and both had a huge influence on Jongen’s viola works – and on their technical difficulty. The young Belgian violist Nathan Braude is simply outstanding in a recital that includes Jongen’s Allegro appassionato Op.79 from 1925, the Introduction & Danse Op.102 from 1935, the Concertino Op.111 from 1940, the two-movement Suite Op.48 and the Andante espressivo. His tone is deep and warm in the lower register, and brilliant and bright, though never thin or lacking in strength, in the upper register. Technically he is flawless and never less than completely musical. He is supported by some terrific piano playing by Jean-Claude Vanden Eynden, who not only has his work cut out in the viola works, but also supplies outstanding performances of the two excellent piano solo pieces that complete the CD: the second Étude de concert Op.65 No.2 and the Soleil à midi Op.33 No.1. The booklet notes make an impassioned plea – and a strong case – for a reassessment of Jongen’s music, and of his place in 20th century music. The charming and beautiful works on this CD make an even stronger one.

There is more viola music – again from a mostly overlooked composer and with another link to Tertis – on the CD of the Complete Works for Viola & Piano by Joseph Jongen (FUGA LIBERA FUG586). Jongen, born in 1873, was also a precociously-gifted musician, and met Tertis in London in 1914 after fleeing from occupied Belgium at the outbreak of the Great War. He also knew the great French viola player Maurice Vieux in the 1920s. Like Bowen, Jongen was a craftsman who produced works of the highest order, but whose reputation suffered as musical styles evolved through the middle of the 20th century. Both Tertis and Vieux were prominent in establishing the viola as a legitimate solo instrument, and both had a huge influence on Jongen’s viola works – and on their technical difficulty. The young Belgian violist Nathan Braude is simply outstanding in a recital that includes Jongen’s Allegro appassionato Op.79 from 1925, the Introduction & Danse Op.102 from 1935, the Concertino Op.111 from 1940, the two-movement Suite Op.48 and the Andante espressivo. His tone is deep and warm in the lower register, and brilliant and bright, though never thin or lacking in strength, in the upper register. Technically he is flawless and never less than completely musical. He is supported by some terrific piano playing by Jean-Claude Vanden Eynden, who not only has his work cut out in the viola works, but also supplies outstanding performances of the two excellent piano solo pieces that complete the CD: the second Étude de concert Op.65 No.2 and the Soleil à midi Op.33 No.1. The booklet notes make an impassioned plea – and a strong case – for a reassessment of Jongen’s music, and of his place in 20th century music. The charming and beautiful works on this CD make an even stronger one.

The ever-reliable Hyperion label has issued two CDs by the Takács Quartet of String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, one featuring the three quartets Op.71 and the other the three quartets Op.74 (Hyperion CDA67781 and CDA67793). All six works were written in Vienna between Haydn’s visits to London in 1791-2 and 1794 and were clearly written for public – as opposed to private – performance, following the success of his Op.64 quartets at the Salomon subscription concerts in London. The Takács Quartet plays with precision, warmth and richness, as you would expect, but the real stars here are the works themselves, amply demonstrating the inexhaustible wit, humour and invention for which Haydn is so justly noted.

The ever-reliable Hyperion label has issued two CDs by the Takács Quartet of String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, one featuring the three quartets Op.71 and the other the three quartets Op.74 (Hyperion CDA67781 and CDA67793). All six works were written in Vienna between Haydn’s visits to London in 1791-2 and 1794 and were clearly written for public – as opposed to private – performance, following the success of his Op.64 quartets at the Salomon subscription concerts in London. The Takács Quartet plays with precision, warmth and richness, as you would expect, but the real stars here are the works themselves, amply demonstrating the inexhaustible wit, humour and invention for which Haydn is so justly noted.

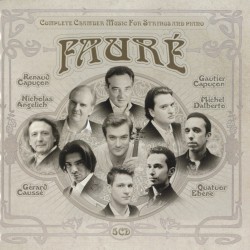

Fauré - Complete Chamber Music for Strings and Piano

Fauré - Complete Chamber Music for Strings and Piano