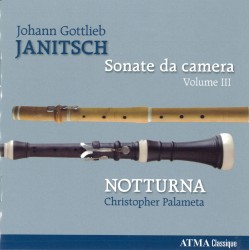

Janitsch - Sonate da camera Volume 3 - Notturna; Christopher Palameta

Janitsch - Sonate da camera Volume3

Janitsch - Sonate da camera Volume3

Notturna; Christopher Palameta

ATMA ACD2 2626

Johann Gottlieb Janitsch (1708-1763) was a court musician for Frederick the Great. As a composer, he embraced the contrapuntal style of the day in his intricate chamber music. Here Notturna, under the leadership of oboist Christopher Palameta perform five of his quadro sonatas.

The works are complex as the counterpoint weaves between the voices with challenging progressions. The ensemble performs with a clear balance between the instruments and a driving group rhythm. Each member of the ensemble is a “star” as the works demand a detailed focus on each note and a sense of the longer line. This is especially evident in Quadro in B-flat major, Op.3, No.1. In this world premiere recording, a rapid change in harmonies in the first five measures foreshadows a fascinating and technically difficult work that seems to embrace the composer’s self-imposed challenge to expand his musical boundaries. In contrast, Op.1, No.5 in C Major is a slightly lighter work, and is the only quartet to use an obbligato cello. The opening dancelike Larghetto alla Siciliana is convincing with its deliberate pizzicato continuo articulation. The second movement fugue from Op.7, No.5 in C Minor for oboe, violin, viola and continuo is an aural treat. At just over two minutes in duration, Palameta’s oboe performance is especially colourful in its detail and ability to cement the parts together.

The balanced performances make this Notturna release one to be enjoyed time and time again.