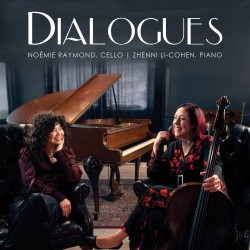

Two monumental sonatas from the early 20th century are presented on Dialogues, the superb new CD from cellist Noémie Raymond and pianist Zhenni Li-Cohen (Leaf Music LM295 leaf-music.ca/music/lm295).

Two monumental sonatas from the early 20th century are presented on Dialogues, the superb new CD from cellist Noémie Raymond and pianist Zhenni Li-Cohen (Leaf Music LM295 leaf-music.ca/music/lm295).

Rachmaninoff’s Cello Sonata in G Minor, Op.19 from 1901 is a glorious four-movement work full of the rich sentimentality and Romanticism so typical of his music. Raymond has a wonderfully deep, warm tone that perfectly illustrates the comment in the booklet note that Rachmaninoff gave the cello line “an expressiveness and intensity previously unheard in the repertoire for cello and piano.” The piano is certainly an equal partner here – in fact, it’s hard to think of a duo sonata in which the piano part is more demanding and more crucial, and Li-Cohen delivers an outstanding performance.

There are times when Rebecca Clarke’s Viola Sonata from 1919, heard here in her own transcription for cello, inhabits the same Romantic world as the Rachmaninoff, but influences of Debussy, Ravel and Vaughan Williams are also there. Again, superb playing and ensemble work – a true dialogue indeed – make for a terrific performance.

Recorded at the beautiful Domaine Forget concert hall in Saint-Irénée, QC the exemplary sound quality completes as fine a cello and piano CD as I’ve heard in a very long time.

American Sketches is the remarkable debut solo album from the Korean-American violinist Kristin Lee, brilliantly supported in all but one of the tracks by pianist Jeremy Ajani Jordan (First Hand Records FHR147 firsthandrecords.com/products-page/upcoming/american-sketches-kristen-lee-violin-jeremy-ajani-jordan-piano).

American Sketches is the remarkable debut solo album from the Korean-American violinist Kristin Lee, brilliantly supported in all but one of the tracks by pianist Jeremy Ajani Jordan (First Hand Records FHR147 firsthandrecords.com/products-page/upcoming/american-sketches-kristen-lee-violin-jeremy-ajani-jordan-piano).

From the moment that John Novacek’s dazzling Intoxication, the first of his Four Rags from 1999, explodes from the speakers you know you are in for something very special, and the standard never drops throughout a mesmerizing and beautifully-recorded CD. The duo swings through Jordan’s arrangements of Gershwin’s But Not for Me and Joplin’s The Entertainer, melts your heart with J. J. Johnson’s lovely 1954 Lament and Henry Thacker Burleigh’s gorgeous Southland Sketches from 1916, and acknowledges contemporary works with Jonathan Ragonese’s fascinating non-poem 4 from 2017/18 and Kevin Puts’ Air from 2000. The final track is Thelonious Monk’s sultry Monk’s Mood from 1943/44, Lee noting that Jordan improvised throughout the Gershwin, Johnson, Joplin and Monk recordings.

The only track on which Jordan is not the pianist is Amy Beach’s lovely Romance Op.23, recorded with Jun Cho in 2023; all other tracks were recorded in November 2019 and March 2020. I’m not sure why we had to wait so long but boy, was it ever worth the wait!

Souvenirs, the new CD from the Swedish-Norwegian violinist Johan Dalene with pianist Peter Friis Johansson is a recital of pieces that have been with him since his childhood, and that he has played in competitions and concerts (BIS-2770 johandalene.com/recordings/souvenirs).

Souvenirs, the new CD from the Swedish-Norwegian violinist Johan Dalene with pianist Peter Friis Johansson is a recital of pieces that have been with him since his childhood, and that he has played in competitions and concerts (BIS-2770 johandalene.com/recordings/souvenirs).

Three virtuoso works form the foundation of the programme: Ravel’s Tzigane opening the disc with Bizet’s arrangement of Saint-Saëns’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso Op.28 at its centre and the “other” Carmen Fantasy, by Franz Waxman and not Sarasate, as the final track. In between are Massenet’s Méditation from Thaïs, Tchaikovsky’s Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Falla’s Spanish Dance No.1, Kreisler’s dazzling solo Recitative and Scherzo-Caprice Op.6 and the delightful Allegro molto by the Swedish violinist/composer Amanda Maier, who died of tuberculosis in 1894 at the age of 41.

Dalene is clearly in his element here in works that he has known and loved for years, ably supported by Johansson.

Navigator of Silences sees American violinist Francesca Anderegg join Brazilian pianist Erika Ribeiro on an album described as exhibiting the cadence and choreography of Brazilian instrumental music, blending samba, chôro and forró with classical music and inspiration from folk, Indigenous and African traditions (Rezurrection Recordz RZRC-0122 rezrecordz.com/navigator-of-silences).

Navigator of Silences sees American violinist Francesca Anderegg join Brazilian pianist Erika Ribeiro on an album described as exhibiting the cadence and choreography of Brazilian instrumental music, blending samba, chôro and forró with classical music and inspiration from folk, Indigenous and African traditions (Rezurrection Recordz RZRC-0122 rezrecordz.com/navigator-of-silences).

Included are works by Yamandu Costa, Radamés Gnattali, Léa Freire, André Mehmari, Luca Raele, Toninho Horta, Bianca Gismonti, Salomão Soares and Clarice Asad, most of them in arrangements and transcriptions by the performers. It’s a selection of really lovely pieces with Anderegg’s strong, warm and bright violin and Ribeiro’s rich, resonant piano providing gorgeous playing on a highly entertaining CD.

On the 2CD release Corelli Violin Sonatas Op.5 violinist Rachel Barton Pine is joined by period instrument specialists David Schrader, John Mark Rozendaal and Brandon Acker in historically informed performances of Arcangelo Corelli’s seminal set of 12 sonatas for violin and continuo from 1700 (Cedille Records CDR 90000 2320 cedillerecords.org/albums/corelli-violin-sonatas-op-5).

On the 2CD release Corelli Violin Sonatas Op.5 violinist Rachel Barton Pine is joined by period instrument specialists David Schrader, John Mark Rozendaal and Brandon Acker in historically informed performances of Arcangelo Corelli’s seminal set of 12 sonatas for violin and continuo from 1700 (Cedille Records CDR 90000 2320 cedillerecords.org/albums/corelli-violin-sonatas-op-5).

Pine’s research led to her holding the violin against her chest, and not on her collarbone, the resulting difference in position for the left hand and – in particular – the bowing arm creating a noticeably different and extremely effective sound.

To capture the nuances of Corelli’s music the performers used a variety of period instruments, Schrader alternating between harpsichord and positive organ, Rozendaal between cello and viola da gamba and Acker between theorbo, archlute and baroque guitar to produce 24 different combinations throughout the recital. In addition, Pine plays the final “Follia” variations on an original-condition six-string Gagliano viola d’amore, made from the same tree as her original-condition Gagliano violin. It provides a dazzling conclusion to a quite superb release.

All of the works on Shapes in Collective Space, the new CD from Tallā Rouge, the Cajun-Persian duo of violists Aria Cheregosha and Laura Spaulding, are world-premiere recordings. Motivated in part by experiencing a close relative lose their memory to dementia, the album is described as a search for light in the passage of time, reflecting on life’s fleeting yet profound moments and drawing from a kaleidoscope of diverse American influences (Bright Shiny Things BSTC-202 brightshiny.ninja/shapes-in-collective-space).

All of the works on Shapes in Collective Space, the new CD from Tallā Rouge, the Cajun-Persian duo of violists Aria Cheregosha and Laura Spaulding, are world-premiere recordings. Motivated in part by experiencing a close relative lose their memory to dementia, the album is described as a search for light in the passage of time, reflecting on life’s fleeting yet profound moments and drawing from a kaleidoscope of diverse American influences (Bright Shiny Things BSTC-202 brightshiny.ninja/shapes-in-collective-space).

Works include Karl Mitze’s Seesaw, Kian Ravaei’s four Iranian-influenced Navazi, Gemma Peacocke’s Fluorescein, Gala Flagello’s Burn as Brightly, Akshaya Avril Tucker’s Breathing Sunlight and Leilehua Lanzilotti’s silhouette, mirror. The title track by inti figgis-vizueta is a particularly fascinating and inventive soundscape.

The playing throughout an engrossing CD is of the highest level.

Partita party – a collaborative work for viola is the new CD from violist Atar Arad and four other violist-composers, all of whom studied with Arad. Inspired by Bach’s Partita No.2 for Solo Violin, it features five movements, each played by the particular composer (SBOV Music SBO224 sbovmusic.com/partita-party).

Partita party – a collaborative work for viola is the new CD from violist Atar Arad and four other violist-composers, all of whom studied with Arad. Inspired by Bach’s Partita No.2 for Solo Violin, it features five movements, each played by the particular composer (SBOV Music SBO224 sbovmusic.com/partita-party).

The concept of an innovative celebration of Bach’s masterpiece featuring new compositions for solo viola was inspired by Arad’s pandemic work on Bach’s monumental Chaconne, Arad having written his own Ciaccona as a commission for the 2021 Hindemith International Viola Competition. Duncan Steele’s Allemanda opens the collection, followed by Yuval Gotlibovich’s Corrente, Melia Watras’ Sarabanda and Rose Wollman’s terrific Giga (the closest to the Bach original); Arad’s original Ciaccona ends the disc.

It’s a brief – just short of 25 minutes – but fascinating CD, rightly described in the publicity release as an exciting new addition to the viola repertoire and a celebration of Bach’s enduring legacy.

The Calidore String Quartet continues its Beethoven project with the 3-CD set Beethoven The Middle Quartets, the second issue in their recording of the complete cycle, having issued The Late Quartets in February 2023 and with the final volume The Early Quartets planned for January 2025 (Signum Classics SIGCD872 signumrecords.com/product/beethoven-quartets-vol-2-middle-string-quartets/SIGCD872).

The Calidore String Quartet continues its Beethoven project with the 3-CD set Beethoven The Middle Quartets, the second issue in their recording of the complete cycle, having issued The Late Quartets in February 2023 and with the final volume The Early Quartets planned for January 2025 (Signum Classics SIGCD872 signumrecords.com/product/beethoven-quartets-vol-2-middle-string-quartets/SIGCD872).

This set contains the three “Razumovsky” quartets Op.59 and the Op.74 and Op.95 works. CD1 has the String Quartet in F Major, Op.59 No.1; CD2 has the String Quartets in E Minor Op.59 No.2 and in C Major Op.59 No.3. The final disc has the String Quartet No.10 in E-flat Major Op.74 “Harp” and the String Quartet No.11 in F Minor Op.95 “Serioso.”

The first set generated extremely positive reviews, and it’s easy to hear why. The quartet members have been together for 14 years, having immersed themselves in Beethoven’s quartets during that time. The unity of the ensemble playing is of the highest quality, and there’s a wonderfully varied dynamic range.

The outstanding series of complete string quartets of the Danish composer Vagn Holmboe (1909-96) continues with Vagn Holmboe String Quartets Vol.3, Denmark’s Nightingale String Quartet again presenting superb performances of warmth, depth and sensitivity. Included on this current disc are two works from the peak of his creativity –String Quartets No.4, Op.63 (1953-54) and No.5, Op.66 (1955) – together with the String Quartet No.16, Op.146 from 1981 (Dacapo Records 8.226214 hbdirect.com/products/holmboe-string-quartets-vol-3).

The outstanding series of complete string quartets of the Danish composer Vagn Holmboe (1909-96) continues with Vagn Holmboe String Quartets Vol.3, Denmark’s Nightingale String Quartet again presenting superb performances of warmth, depth and sensitivity. Included on this current disc are two works from the peak of his creativity –String Quartets No.4, Op.63 (1953-54) and No.5, Op.66 (1955) – together with the String Quartet No.16, Op.146 from 1981 (Dacapo Records 8.226214 hbdirect.com/products/holmboe-string-quartets-vol-3).

Holmboe’s 21 numbered quartets preoccupied him throughout almost half a century, moving from early influences of Bartók and Shostakovich to his distinctive personal method of metamorphosis of thematic and motivic fragments. The Nightingale Quartet’s committed performances of these strongly tonal and immediately accessible works continue to make the strongest case for their recognition as one of the major quartet series of the 20th century.

The Quatuor Diotima celebrates the bicentennial of the birth of Anton Bruckner with Bruckner & Klose String Quartets, presenting the three works Bruckner wrote as composition exercises when studying with Otto Kitzler in 1861-63 together with the only string quartet written by his student Friedrich Klose (1862-1942) (Pentatone PTC5187217 pentatonemusic.com/product/bruckner-klose-string-quartets).

The Quatuor Diotima celebrates the bicentennial of the birth of Anton Bruckner with Bruckner & Klose String Quartets, presenting the three works Bruckner wrote as composition exercises when studying with Otto Kitzler in 1861-63 together with the only string quartet written by his student Friedrich Klose (1862-1942) (Pentatone PTC5187217 pentatonemusic.com/product/bruckner-klose-string-quartets).

The main Bruckner work is his String Quartet in C Minor, WAB111, with the Rondo in C Minor, WAB208 a possible alternative finale. The Theme with Variations in E-flat, WAB210 is the third work. They are solid and accomplished pieces – as you would expect from a composer nearing 40 years of age – and despite tending to sound more concerned with structure than content have a great deal to offer.

Klose studied with Bruckner from January 1886 to July 1889 and wrote his lengthy String Quartet in E-flat in 1908-11. Subtitled “A tribute paid in four instalments to my stern German schoolmasters” it clearly references classical forms and structures, but with what the booklet note calls “an almost unprecedented wealth of musical ideas.”

Sibelius: Works for Violin and Orchestra is the new CD from James Ehnes and the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra under Edward Gardner (Chandos CHSA 5267 chandos.net/products/catalogue/CHSA%205267).

Sibelius: Works for Violin and Orchestra is the new CD from James Ehnes and the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra under Edward Gardner (Chandos CHSA 5267 chandos.net/products/catalogue/CHSA%205267).

Ehnes’ playing in the Violin Concerto Op.47 is, as always, seemingly effortless perfection, with a smooth warmth – no icy Finnish landscape here – but also strength and power. Gardner and the orchestra provide spirited accompaniment, but this is perhaps one concerto that doesn’t need a sheen of perfection to be most effective. Still, Ehnes is always a force to be reckoned with.

He certainly shines throughout the short pieces which, although beautifully written, don’t come close to the concerto in stature: the Two Serenades Op.69; the Two Pieces Op.77; the Two Humoresques Op.87; the Four Humoresques Op.89 and the Suite in D Minor Op.117.

There’s a tragic modern-day relevance to the new CD Thomas de Hartmann Rediscovered, with one of the two concertos by the Ukrainian composer (1884-1956) written in 1943 in occupied France described as mourning the destruction of Ukraine by war (Pentatone PTC5187076 pentatonemusic.com/product/thomas-de-hartmann-rediscovered).

There’s a tragic modern-day relevance to the new CD Thomas de Hartmann Rediscovered, with one of the two concertos by the Ukrainian composer (1884-1956) written in 1943 in occupied France described as mourning the destruction of Ukraine by war (Pentatone PTC5187076 pentatonemusic.com/product/thomas-de-hartmann-rediscovered).

Joshua Bell is the soloist in the 1943 Violin Concerto Op.66, with the Ukrainian INSO-Lviv Symphony Orchestra under Dalia Stasevska. It’s the world-premiere commercial recording of a cinematic, four-movement work, with Bell calling it heart-wrenching and uplifting, and commenting that he was “astonished that such a powerful work could have escaped me and most classical music listeners until now.”

The Cello Concerto Op.57 from 1935 is a lush, Romantic work with an even more cinematic feel than the violin concerto, at times evoking Hollywood biblical epics. Matt Haimovitz is the soloist, with the MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra under Dennis Russell Davies. Haimovitz notes that de Hartmann was deeply affected by Jewish music and culture, and while Ukrainian folk idioms pervade the finale the prayerful middle movement channels the voice of a Jewish cantor.

Goodness knows where the viola repertoire would be without Lionel Tertis. Not only did the English violist almost single-handedly establish the viola as a solo concert instrument, he was also the recipient of numerous works written specifically for him. Two of these are presented on the outstanding CD York Bowen & William Walton Viola Concertos, with soloist Diyang Mei, principal viola of the Berlin Philharmoniker, and the Deutsche Radio Philharmonie conducted by Brett Dean, himself a violist (SWR Music SWR19158CD naxos.com/CatalogueDetail/?id=SWR19158CD).

Goodness knows where the viola repertoire would be without Lionel Tertis. Not only did the English violist almost single-handedly establish the viola as a solo concert instrument, he was also the recipient of numerous works written specifically for him. Two of these are presented on the outstanding CD York Bowen & William Walton Viola Concertos, with soloist Diyang Mei, principal viola of the Berlin Philharmoniker, and the Deutsche Radio Philharmonie conducted by Brett Dean, himself a violist (SWR Music SWR19158CD naxos.com/CatalogueDetail/?id=SWR19158CD).

The orchestral music of Bowen is surely overdue for reappraisal, his strongly tonal and Romantic style resulting in his larger works being essentially ignored following his death in 1961. The Viola Concerto in C Minor, Op.25 from 1907 is the real gem here, a rhapsodic work that sweeps you along with it, leaving you wondering how on earth it isn’t at the front and centre of the concerto repertoire. It’s wonderful playing from all concerned.

Walton’s Concerto in A Minor was written in 1929 at Thomas Beecham’s suggestion but surprisingly premiered by Paul Hindemith and not Tertis, who initially found the work to be too modern. It’s not lacking for top-notch recordings, but this superb performance will take some beating.

Nightscapes, the first album from harpist Magdalena Hoffmann was reviewed here in April 2022, and the beautifully nuanced and virtuosic playing noted at that time is once again fully evident in her new CD Fantasia (Deutsche Grammophon 00028948659128 deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/fantasia-magdalena-hoffmann-13555).

Nightscapes, the first album from harpist Magdalena Hoffmann was reviewed here in April 2022, and the beautifully nuanced and virtuosic playing noted at that time is once again fully evident in her new CD Fantasia (Deutsche Grammophon 00028948659128 deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/fantasia-magdalena-hoffmann-13555).

The focus this time is on the Baroque period, with a collection of fantasias and preludes originally composed for keyboard or lute by J. S. Bach, his sons Wilhelm Friedmann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, plus contemporaries George Frideric Handel and Silvius Leopold Weiss.

Hoffmann uses the music here to explore the resonance and versatility of her instrument in a delightful recital of predominantly brief works, Bach’s sons providing the three more substantial offerings: W. F. Bach’s Fantasia in D Minor, F19; and C. P. E. Bach’s Fantasia in E-flat Major, H348 and in particular his remarkable Fantasia in F-sharp Minor, H300, “C. P. E. Bachs Empfindungen.”

It’s more outstanding playing from a supremely-gifted performer.

On Pastiches guitarist John Schneider adopts a fascinating and innovative approach to pieces that pay homage to music of the past (MicroFest Records M-F 27 microfestrecords.com/pastiches).

On Pastiches guitarist John Schneider adopts a fascinating and innovative approach to pieces that pay homage to music of the past (MicroFest Records M-F 27 microfestrecords.com/pastiches).

Schneider wondered how works written “in the style of” pastiches would sound if performed in the appropriate temperaments of the period they evoke. The result is a CD using a variety of refretted guitars and Well-Tempered, Meantone and Just Intonation tunings.

There are older works by Manuel Ponce, Alonso Mudarra and Mauro Giuliani, with Dusan Bogdanovich’s Renaissance Micropieces from 2014 the most recent. Percussionist Matthew Cook provides support on six short pieces by Lou Harrison and Benjamin Britten’s Courtly Dances from Gloriana, all arranged by Schneider. Gloria Cheng adds harpsichord to Ponce’s Preludio in E.

It’s an interesting experiment, but I’m not sure that it ever amounts to anything more than that; despite the fine playing there’s a resulting and understandable loss of brightness to many of the pieces – most of which were after all written for a modern instrument – and consequently a limited dynamic range.

More Bach, Please!

More Bach, Please!