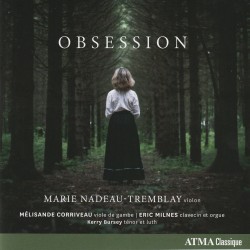

Baroque violinist Marie Nadeau-Tremblay admits to having an obsessive personality and to having crafted her new album Obsession with that in mind. She is supported by Mélisande Corriveau on viola da gamba, Eric Milnes on harpsichord and organ, and Kerry Bursey on lute (ATMA Classique ACD2 2825 atmaclassique.com/en/product/obsession).

Baroque violinist Marie Nadeau-Tremblay admits to having an obsessive personality and to having crafted her new album Obsession with that in mind. She is supported by Mélisande Corriveau on viola da gamba, Eric Milnes on harpsichord and organ, and Kerry Bursey on lute (ATMA Classique ACD2 2825 atmaclassique.com/en/product/obsession).

Nadeau-Tremblay notes that obsessive characteristics are present in each of the works here – as themes and variations, repeated ground bass lines or returning rondo themes – with the album consisting entirely of minor key pieces adding to the feeling of being stuck in an obsessive loop.

An engrossing recital of predominantly late 17th-century works includes two by Biber – his Sonata No.2 in D Minor, C139 and Rosary Sonata No.1 in D Minor, “Annunciation” – two by Buxtehude – his Trio Sonata in A Minor, BuxWV272 and Trio Sonata in G Minor, BuxWV261 – Michel Farinel’s Faronells Division Upon a Ground (La Folia) and François Francœur’s Sonata for Violin and Continuo in G Minor, Op.2 No.6.

Bursey is the tenor soloist in the lovely, anonymous Une jeune fillette, and Nadeau-Tremblay is terrific in Louis-Robert Guillemain’s extremely difficult Amusement for violin solo, Op.18 No.1 “La Furstemberg” from 1755.

Nadeau-Tremblay plays with outstanding clarity and beauty, her flawless technical facility married to an innate and sensitive musicianship in a superb release.

One – New Music for Unaccompanied Violin, a collection of world premiere recordings, is violinist Patrick Yim’s third album of solo violin music and features six works commissioned between 2020 and 2023 (New Focus Recordings FCR411 newfocusrecordings.com/catalogue/patrick-yim-one-new-music-for-unaccompanied-violin).

One – New Music for Unaccompanied Violin, a collection of world premiere recordings, is violinist Patrick Yim’s third album of solo violin music and features six works commissioned between 2020 and 2023 (New Focus Recordings FCR411 newfocusrecordings.com/catalogue/patrick-yim-one-new-music-for-unaccompanied-violin).

Ilari Kaila’s high-energy moto perpetuo Solitude opens the disc. Juri Soo’s title track One is a cycle of 12 widely-varied vignettes representing the months of the year. All four opening works on the CD were written during the pandemic lockdown, Takuma Itoh’s A Melody from an Unknown Place and Páll Ragnar Pálsson’s Hermitage are both meditations on the loneliness and spirituality of the isolation. Matthew Schreibeis’ Fragile Remembrance and John Liberatore’s Strange, High Sky are both from 2023, the former essentially an ABA arc and the latter inspired by Lu Sun’s Wild Grass stories.

“Yim plays with virtuosity and powerful expression,” says the release blurb in a perfect assessment.

On the digital release Viola Fantasies violist Mischa Galaganov presents the 12 Fantasies for Bass Viol (1735) by Georg Philip Telemann, the first recording on viola of the only known solo works from a major Baroque composer to almost ideally complement the modern viola’s range and tonal characteristics (Navona NV6692 navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6692).

On the digital release Viola Fantasies violist Mischa Galaganov presents the 12 Fantasies for Bass Viol (1735) by Georg Philip Telemann, the first recording on viola of the only known solo works from a major Baroque composer to almost ideally complement the modern viola’s range and tonal characteristics (Navona NV6692 navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6692).

Galaganov uses gut strings and modern tunings in his own arrangements of the works, with such issues as dynamics, tempi and ornamentation being determined by his research, experience and instincts. If you are familiar with Telemann’s12 Fantasies for Solo Violin then you will know what to expect here: a set of short, inventive works, mostly of three brief and contrasting movements, that require a great deal more technical skill than you might imagine given the deceptively easy flow of the music. Galaganov is superb throughout a fascinating recital, with the two Vivaces and the Presto in the four-movement Fantasie No.2 particular standouts.

The release publicity referred to these works as “soon-to-be viola standards,” and it’s easy to see – and hear – why.

Violinist Francesca Dego completes her celebration of Ferruccio Busoni’s centenary year with Busoni Violin Sonatas & Four Bagatelles, accompanied by her regular recital pianist Francesca Leonardi (Chandos CHAN 20304 chandos.net/products/reviews/CHAN_20304).

Violinist Francesca Dego completes her celebration of Ferruccio Busoni’s centenary year with Busoni Violin Sonatas & Four Bagatelles, accompanied by her regular recital pianist Francesca Leonardi (Chandos CHAN 20304 chandos.net/products/reviews/CHAN_20304).

The two sonatas, No.1 Op.29 K234 and No.2 Op.36a K244 are both in E minor and reflect the composer’s grounding in the German Romantic tradition. The first, from 1890 is close to the Brahms D minor sonata in feel, while the second, from 1900 is a more complex work centred on a chorale from the Anna Magdalena Notebook and feeling like a single-movement arc, its ten mostly short sections played without a break.

The Four Bagatelles Op.28 K229 from 1888 that end the disc are brief – only just over six minutes in total – early works written for the 7-year-old child prodigy Egon Petri, who would later become a Busoni student.

As always, Dego plays with warmth and style, sensitively supported by Leonardi.

Inspired by her research project “Latvian Classical Violin Music in Transition, c.1980-2000” the Australia-based Latvian violinist Sophia Kirsanova presents world premiere recordings of stylistically diverse works for violin by Latvian composers on The Morning Mist, a musical reflection on a significant period that saw the collapse of the Soviet Union and Latvia regaining its independence (SKANI LMIC167 sophiakirsanova.com).

Inspired by her research project “Latvian Classical Violin Music in Transition, c.1980-2000” the Australia-based Latvian violinist Sophia Kirsanova presents world premiere recordings of stylistically diverse works for violin by Latvian composers on The Morning Mist, a musical reflection on a significant period that saw the collapse of the Soviet Union and Latvia regaining its independence (SKANI LMIC167 sophiakirsanova.com).

Three works represent music of today’s Latvia: Ēriks Ešenvalds’ title track, with pianist Agnese Eglina; Linda Leimane’s Architectonics of a Crystal Soul, with the Syzygy Ensemble; and Platon Buravicky’s Angel’s Gaze, with pianist Georgina Lewis. Amir Farid is the pianist for Pēteris Vasks’ Little Summer Music, a set of five brief but delightful pieces, but the highlight here is Aivars Kalējs’ monumental Toccata for Solo Violin Op.40, a striking work, heavily influenced by Bach, that draws particularly outstanding playing from Kirsanova, who handles a variety of styles and techniques with ease and musical intelligence throughout the CD.

James Ehnes switches to viola on Ehnes & Armstrong Play Brahms & Schumann, accompanied by his regular recital partner Andrew Armstrong – and it’s not just any viola, but the 1696 “Archinto” Stradivarius viola on loan from the Royal Academy of Music (Onyx ONYX4256 onyxclassics.com/release/ehnes-armstrong-play-brahms-schumann-brahms-sonatas-op-120-weigenlied-schumann-marchenbilder).

James Ehnes switches to viola on Ehnes & Armstrong Play Brahms & Schumann, accompanied by his regular recital partner Andrew Armstrong – and it’s not just any viola, but the 1696 “Archinto” Stradivarius viola on loan from the Royal Academy of Music (Onyx ONYX4256 onyxclassics.com/release/ehnes-armstrong-play-brahms-schumann-brahms-sonatas-op-120-weigenlied-schumann-marchenbilder).

The Schumann work that opens the disc is the Märchenbilder (Fairy-Tale Pictures) Op.113, a group of four pieces written in a mere few days in March 1851. They create a sense of fantasy rather than depicting specific scenes, and are full of strong rhythmic and melodic contrast.

Brahms had advised his publisher that he was considering retirement when he encountered the exceptional playing of clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld, the four works he wrote for him – the Clarinet Trio Op.114, the Clarinet Quintet Op.115 and the two Clarinet Sonatas Op.120 – being the last chamber compositions of Brahms’ career. It’s the latter works that are featured here: the Sonata in F Minor Op.120 No.1 and the Sonata in E Major Op.120 No.2, both in the arrangements made by the composer. His Wiegenlied Op.49 No.4 – the well-known Brahms Lullaby – completes the recital.

The playing is all that you would expect: warm, expressive perfection from Ehnes and sensitive, resonant support from Armstrong.

Encircling, the new CD from violist Daphne Gerling and pianist Tomoko Kashiwagi, features music by the English violist and composer Rebecca Clarke and three of her female contemporaries. It was inspired by Gerling’s doctoral research that celebrated the centennial of the 1919 Berkshire Composition Competition in America (Acis APL53974 acisproductions.com/encircling-daphne-gerling).

Encircling, the new CD from violist Daphne Gerling and pianist Tomoko Kashiwagi, features music by the English violist and composer Rebecca Clarke and three of her female contemporaries. It was inspired by Gerling’s doctoral research that celebrated the centennial of the 1919 Berkshire Composition Competition in America (Acis APL53974 acisproductions.com/encircling-daphne-gerling).

Clarke’s Passacaglia on an Old English Tune opens the disc. The Viola Sonata Op.7 by the virtually unknown English composer Kalitha Dorothy Fox (1894-1934) was rediscovered as one result of the project to find as many of the 72 entries in the 1919 competition as possible; it’s a world premiere recording.

The Viola Sonata Op.25 by the French composer Marcelle Soulage (1894-1970) may possibly have been entered in the competition, although the entry deadline preceded the sonata’s November 1919 completion. The Fantaisie Op.18 by Hélène Fleury-Roy (1876-1957) completes the CD.

There’s nothing spectacular here, but it’s still a beautifully played and recorded recital of finely crafted and fascinating works.

Cellist Alisa Weilerstein and her longtime recital partner Inon Barnaton are in fine form on Brahms Cello Sonatas, pairing the two works with their own arrangement of one of the violin sonatas (Pentatone PYC5187215 pentatonemusic.com/product/brahms-cello-sonatas).

Cellist Alisa Weilerstein and her longtime recital partner Inon Barnaton are in fine form on Brahms Cello Sonatas, pairing the two works with their own arrangement of one of the violin sonatas (Pentatone PYC5187215 pentatonemusic.com/product/brahms-cello-sonatas).

The Cello Sonata No.1 in E Minor, Op.38 from 1865 clearly illustrates Brahms’ intention to treat the piano as an equal partner in the duo – it should “under no circumstances assume a purely accompanying role.” The Cello Sonata No.2 in F Major, Op.99 from 1886 is a mature work, although not with the autumnal nature of so many of his late chamber works.

In between the two sonatas is the duo’s arrangement of the Violin Sonata No.1 in G Major, Op.78. There was a contemporary arrangement of this work, transposed into D major, by Paul Klengel, but Barnaton always felt that the loss of the original key’s timbre and colour, together with the changes to the piano part and the high register cello writing rendered it unconvincing.

Played here in the original key with the cello mostly an octave lower, Barnaton feels that “those dark colours” are restored, albeit more so now that the cello part is in the middle of the piano range for much of the time. Still, there’s no doubting the quality of the playing on a simply lovely CD.

The Oslo String Quartet launches their very own label with Learn To Wait, a digital-only release that features music by Benjamin Britten, György Ligeti and Nils Henrik Asheim, whose third quartet gives the project its title (OSQ01 stringquartet.com).

The Oslo String Quartet launches their very own label with Learn To Wait, a digital-only release that features music by Benjamin Britten, György Ligeti and Nils Henrik Asheim, whose third quartet gives the project its title (OSQ01 stringquartet.com).

Britten’s String Quartet No.1 from 1941 was written while he was in the United States, having left England at the start of the war. Although a relatively early work, its brilliance of invention, scoring and technique is a clear indicator of how the composer’s career would develop.

The central work in the recital is Asheim’s String Quartet No.3, Learn To Wait, composed during the pandemic lockdown. It’s a ten-minute single movement featuring note clusters, harmonics and extended bowing techniques that apparently seemed a logical choice for the disc as the Oslo players happened to be working on it at the same time as the other two quartets; however, it has trouble holding its own in such company.

Ligeti’s String Quartet No.1, Métamorphoses nocturnes from 1953-54 clearly has more to say right from the start, the range of its fascinating soundscape showing a personal voice emerging from the influence of both Bartók and Schoenberg’s 12-tone system.

Works by Vivaldi and the Irish composer Ailbhe McDonagh (b.1982) are featured on The Irish Seasons, the debut solo album from the Irish violinist Lynda O’Connor. David Brophy conducts the Anamus string ensemble (Avie AV2688 avie-records.com/releases/the-irish-seasons-ailbhe-mcdonagh-•-antonio-vivaldi).

Works by Vivaldi and the Irish composer Ailbhe McDonagh (b.1982) are featured on The Irish Seasons, the debut solo album from the Irish violinist Lynda O’Connor. David Brophy conducts the Anamus string ensemble (Avie AV2688 avie-records.com/releases/the-irish-seasons-ailbhe-mcdonagh-•-antonio-vivaldi).

O’Connor feels that there are similarities between Irish and Baroque music, both structurally and in ornamentation, and the pairing of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons with the world premiere recording of McDonagh’s The Irish Four Seasons was a natural choice. The former is an intimate, warm and upbeat performance, but it’s really the McDonagh work that drives the CD – and it’s a real gem.

Each of the four seasons is represented by a single movement. The lovely Spring – Earrach (pronounced AH rakh) has a slow Irish air on each side of a lively reel, the ABA form mirroring the fast-slow-fast pattern of each of the Vivaldi concertos. Summer – Samhradh (SAU rah), also in ABA form, is in the same G minor key as Vivaldi’s Summer, and quotes from the latter’s third movement. Autumn – Fómhar (FOHR) with its jig and turbulent cross-string patterns, has a clear Vivaldi feel, and Winter – Geimhreadh (GEE rah) includes themes from the three previous movements.

“Has there ever been a composer of more consistent eloquence?”, says cellist Steven Isserlis about the subject of his new CD Music of the Angels – Cello Concertos, Sonatas & Quintets by Luigi Boccherini on which he also directs the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (Hyperion CDA68444 hyperion-records.co.uk/dc.asp?dc=D_CDA68444).

“Has there ever been a composer of more consistent eloquence?”, says cellist Steven Isserlis about the subject of his new CD Music of the Angels – Cello Concertos, Sonatas & Quintets by Luigi Boccherini on which he also directs the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (Hyperion CDA68444 hyperion-records.co.uk/dc.asp?dc=D_CDA68444).

Boccherini (1743-1805) spent most of his adult life in Spain in what Isserlis, in his customary exemplary booklet essay calls “his own idyllic realm of the senses.” The CD’s title comes from a musical dictionary published a few years after Boccherini’s death that described his adagios as giving one “an idea of the music of the angels.”

Faithful editions of Boccherini’s music, however, are a relatively recent development. The two concertos here – the Concerto No.2 in A Major G475, the authenticity of which was originally questioned, and the Concerto No.6 in D Major G479, are from Boccherini’s early years as a touring virtuoso.

Maggie Cole is the harpsichordist in the Sonata in C Minor G2b, and Luise Buchberger the second cellist in the gorgeous Sonata in F Major G9. The String Quintet in D Minor G280 is at the centre of the recital, and the famous Minuetto & Trio from the String Quintet in E Major G275 ends an outstanding CD of beautiful – and, yes, eloquent – playing.

There’s more fine cello playing on Dvořák Cello Concerto & Pieces, with cellist Benedict Kloeckner accompanied by the Romanian Chamber Orchestra under Cristian Măcelaru and by pianist Danae Dörken in a recital of Dvořák’s cello works “all of which,” it is claimed, “are collected here for the first time on a CD.” There’s no sign of the Slavonic Dance Op.48 No.3, though (SWR Berlin Classics 0303412BC berlin-classics-music.com/en/album/885470035130-dvorak-cello-concerto-pieces).

There’s more fine cello playing on Dvořák Cello Concerto & Pieces, with cellist Benedict Kloeckner accompanied by the Romanian Chamber Orchestra under Cristian Măcelaru and by pianist Danae Dörken in a recital of Dvořák’s cello works “all of which,” it is claimed, “are collected here for the first time on a CD.” There’s no sign of the Slavonic Dance Op.48 No.3, though (SWR Berlin Classics 0303412BC berlin-classics-music.com/en/album/885470035130-dvorak-cello-concerto-pieces).

Kloeckner’s warm tone and outstanding technique make for a fine reading of the Cello Concerto in B Minor Op.104, recorded in a live single-take performance in the Stadttheater Koblenz and featuring a particularly lovely middle movement. The cello and piano versions of Waldsruhe Op.68 No.5 (Silent Woods) and the Rondo in G Minor Op.94 were both used in Dvořák’s farewell tour of Bohemia before leaving for America.

The Slavonic Dance Op.46 No.8 and the rarely-performed Polonaise in A Major Op.Post.B94 are both Dvořák originals, and Kloeckner’s own arrangements of Songs my mother taught me Op.55 No.4 and Leave me alone Op.82 No.1, the song that makes a crucial emotional contribution to the concerto, are the remaining tracks on an excellent disc.

A warm and finely-judged performance of Robert Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A Minor, Op.129 anchors the 2CD set Love Letters – Tribute to Clara & Robert Schumann, with cellist Christian-Pierre La Marca supported by the Philharmonia Orchestra under Raphaël Merlin and pianist Jean-Frédéric Neuberger (Naïve V7364 christianpierrelamarca.com/en/music).

A warm and finely-judged performance of Robert Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A Minor, Op.129 anchors the 2CD set Love Letters – Tribute to Clara & Robert Schumann, with cellist Christian-Pierre La Marca supported by the Philharmonia Orchestra under Raphaël Merlin and pianist Jean-Frédéric Neuberger (Naïve V7364 christianpierrelamarca.com/en/music).

Described as “an anthem to eternal love” the release was inspired by the intimate love letters exchanged between Robert and Clara Schumann, while seeking to root those letters in a modern context by inviting four contemporary composers to add their own vision of love in a world of digital connection.

CD1 opens with the concerto and also includes Robert’s Fantasiestücke Op.73 and his Adagio and Allegro Op.70. It ends with La Marca’s arrangements of the two movements from the collaborative F-A-E Sonata written by Schumann, Brahms and Albert Dietrich for the violinist Joseph Joachim: the Intermezzo by Schumann and the Scherzo by Brahms, the latter a close associate of both Schumanns.

CD2 is a somewhat less successful mixed bag, with three works by Clara and four by Robert interwoven with world-premiere recordings of Fabien Waksman’s Replika, Michelle Ross’ Désenvoyé, Neuberger’s Vibrating and Patricia Kopatchinskaja’s Klingelnseel & Choral and SMS.

Beethoven – The Forgotten Concerto for Fortepiano, Op.61a

Beethoven – The Forgotten Concerto for Fortepiano, Op.61a