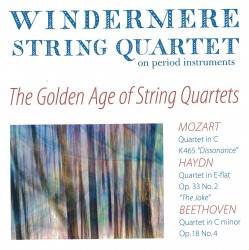

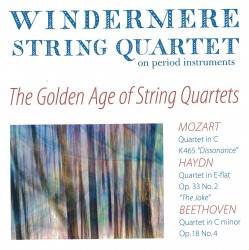

Toronto’s Windermere String Quartet was founded in 2005, but has only just released its first CD, The Golden Age of String Quartets, on Alison Melville’s Pipistrelle label (PIP0112). The ensemble bills itself as the Windermere String Quartet “on period instruments” and the players, violinists Rona Goldensher and Elizabeth Loewen Andrews, violist Anthony Rapoport and cellist Laura Jones, all have extensive experience with leading period instrument ensembles.

Toronto’s Windermere String Quartet was founded in 2005, but has only just released its first CD, The Golden Age of String Quartets, on Alison Melville’s Pipistrelle label (PIP0112). The ensemble bills itself as the Windermere String Quartet “on period instruments” and the players, violinists Rona Goldensher and Elizabeth Loewen Andrews, violist Anthony Rapoport and cellist Laura Jones, all have extensive experience with leading period instrument ensembles.

Their debut CD highlights the period at the heart of their repertoire, with Mozart’s Quartet in C Major K465, the “Dissonance,” Haydn’s Quartet in E-Flat Major Op.33 No.2, “The Joke,” and Beethoven’s Quartet in C Minor Op.18 No.4.

As you would expect, there is no overtly “romantic” approach to the playing here, but these are terrific interpretations, with fine ensemble playing, great dynamics and expression, excellent choices of tempo, sensitivity in the Mozart, a fine sense of humour in the Haydn and real passion in the Beethoven.

The recordings were made almost two years ago in St. Anne’s Anglican Church in Toronto, with the expert team of Norbert Kraft and Bonnie Silver, and the ambience is spacious and reverberant.

Period performances often display a sparsity of vibrato and a softness of attack that can make them sound somewhat flat and lifeless, and lacking in fullness and warmth — or at least, warmth the way we have come to expect it. There is never any danger of that here, though. These are period performances that blend life, spirit and soul with a perfectly-judged sensitivity for contemporary style and practice. It’s the perfect marriage, and hopefully we won’t have to wait too long for further offspring to accompany this exemplary debut disc.

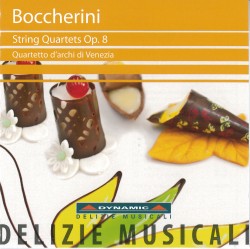

Two interesting CDs of early Italian string quartets arrived recently, neither of which turned out to be quite what I expected.

Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805) is mostly remembered for his famous Minuet, but along with Haydn he was in at the birth of the string quartet form, writing close to 100 quartets, almost always in groups of six, starting with his Op.2 in 1761. The six String Quartets Op.8 from 1768 are featured on a budget re-issue CD from the Italian DYNAMIC label in excellent 1994 performances by the Quartetto d’archi di Venezia (DM8027).

Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805) is mostly remembered for his famous Minuet, but along with Haydn he was in at the birth of the string quartet form, writing close to 100 quartets, almost always in groups of six, starting with his Op.2 in 1761. The six String Quartets Op.8 from 1768 are featured on a budget re-issue CD from the Italian DYNAMIC label in excellent 1994 performances by the Quartetto d’archi di Venezia (DM8027).

Despite their brevity — the longest quartet is only 14 minutes long — and their limited emotional range, this is in no way merely functional music but true part-writing that is both well-balanced and idiomatic.

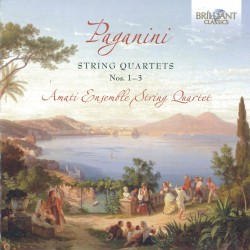

Niccolo Paganini wrote only three works in the quartet genre, but despite their being written some 50 years after Boccherini’s there is virtually no part-writing; it’s almost all first violin solo with string accompaniment. Perhaps surprisingly, this is not because Paganini wanted to display his virtuosic technique: they are, in fact, very much of their time. Paganini was a close friend of Rossini, and the music here — like Rossini’s — is essentially melodic, with no attempt at dialogue. The String Quartets Nos.1–3 are charming and competent, but with no great depth, and receive effortless performances by the Amati Ensemble String Quartet on Brilliant Classics (94287). These quartets live or die on the skills of the first violin, and happily, Dutch violinist Gil Sharon is more than up to the task.

Niccolo Paganini wrote only three works in the quartet genre, but despite their being written some 50 years after Boccherini’s there is virtually no part-writing; it’s almost all first violin solo with string accompaniment. Perhaps surprisingly, this is not because Paganini wanted to display his virtuosic technique: they are, in fact, very much of their time. Paganini was a close friend of Rossini, and the music here — like Rossini’s — is essentially melodic, with no attempt at dialogue. The String Quartets Nos.1–3 are charming and competent, but with no great depth, and receive effortless performances by the Amati Ensemble String Quartet on Brilliant Classics (94287). These quartets live or die on the skills of the first violin, and happily, Dutch violinist Gil Sharon is more than up to the task.

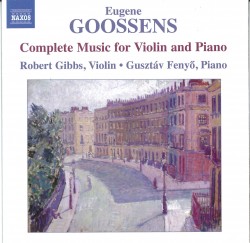

The Goossens family was at the centre of English musical life in the first half of the 20th century. Eugene Goossens (1893-1962) is now mostly remembered for his conducting career, particularly in the USA, but he was trained as a violinist and composer. Naxos has issued an outstanding CD of his Complete Music for Violin and Piano, featuring violinist Robert Gibbs and pianist Gusztav Fenyo (8.572860).

The Goossens family was at the centre of English musical life in the first half of the 20th century. Eugene Goossens (1893-1962) is now mostly remembered for his conducting career, particularly in the USA, but he was trained as a violinist and composer. Naxos has issued an outstanding CD of his Complete Music for Violin and Piano, featuring violinist Robert Gibbs and pianist Gusztav Fenyo (8.572860).

The violin sonatas nos.1 and 2, from 1918 and 1930 respectively, are the major works here. Heifetz played the latter, and Goossens transcribed the Romance from his opera Don Juan de Manara for him. The Lyric Poem and the Old Chinese Folk-Song complete the disc.

Gibbs is simply perfect for this material, technically stunning, with a warm, sweet, lyrical sound and a fast and fairly constant vibrato very reminiscent of Heifetz. Fenyo is every bit his equal, especially in the demanding second sonata.

There is yet another CD – the third I’ve received in the past year – of the Six Sonatas for Solo Violin by Eugene Ysaÿe, this time by the American violinist Tai Murray (harmonia mundi HMU 907569). Given the number of versions available, these works obviously continue to be highly regarded and valued by violinists, even if music lovers in general seem to be unaware of their quality and significance.

There is yet another CD – the third I’ve received in the past year – of the Six Sonatas for Solo Violin by Eugene Ysaÿe, this time by the American violinist Tai Murray (harmonia mundi HMU 907569). Given the number of versions available, these works obviously continue to be highly regarded and valued by violinists, even if music lovers in general seem to be unaware of their quality and significance.

This is Murray’s debut recording for the label, and it’s a real winner. She has a big, warm tone, and always keeps a clear inner line through the maze of multiple stoppings and technical challenges, with never a strained moment or jagged edge.

It’s almost impossible to recommend a single CD of these works, given the number currently available, but you really can’t go far wrong with this beautifully recorded and impeccably played interpretation.

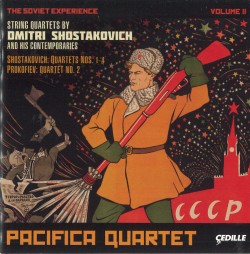

The Chicago label Cedille has issued Volume II of The Soviet Experience, the series of String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich and his Contemporaries (CDR 90000 130), and it maintains the standard set by the first volume, reviewed in this column two months ago.

The Chicago label Cedille has issued Volume II of The Soviet Experience, the series of String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich and his Contemporaries (CDR 90000 130), and it maintains the standard set by the first volume, reviewed in this column two months ago.

This time, the four Shostakovich quartets Nos.1-4 are paired with the String Quartet No.2 of Sergei Prokofiev, and the performances by the Pacifica Quartet once again show their great affinity for the music of this country and this period. The booklet notes and cover art are again outstanding.

I hope we won’t have to wait too long for the remaining volumes in this terrific series.

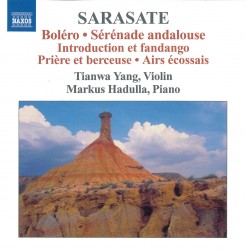

Naxos has issued another volume in its ongoing series of the Complete Violin Works of Pablo Sarasate. I think it’s volume six of a planned seven or eight – depending on which CD cover you believe – but I’m not sure, as the numbering system is a bit confusing: this is apparently Volume 3 of the Music for Violin and Piano (8.570893) and there have also been three numbered volumes of Music for Violin and Orchestra, two of which have been reviewed here. No matter, because it’s the music that counts, and once again the standard of composition never lags throughout the 14 short pieces.

Naxos has issued another volume in its ongoing series of the Complete Violin Works of Pablo Sarasate. I think it’s volume six of a planned seven or eight – depending on which CD cover you believe – but I’m not sure, as the numbering system is a bit confusing: this is apparently Volume 3 of the Music for Violin and Piano (8.570893) and there have also been three numbered volumes of Music for Violin and Orchestra, two of which have been reviewed here. No matter, because it’s the music that counts, and once again the standard of composition never lags throughout the 14 short pieces.

In his booklet notes, Josef Gold rightly stresses not only Sarasate’s outstanding melodic gifts, which were far ahead of the other composers of salon pieces at the time, but also his skill in the piano accompaniments. Both aspects are fully evident on this delightful CD, which once again features the outstanding Tianwa Yang accompanied by Markus Hadulla. Melody does quite often overshadow pure virtuosity, but Yang is perfectly at ease with both. Hadulla supplies sympathetic and idiomatic support throughout.

Most of the tracks on this CD were recorded in Germany in 2007, with three of the longer tracks recorded there in late 2010. Yang apparently started the series in 2004, and while it seems to be taking quite some time to reach completion the quality of the playing and the standard of the production has remained extremely high.

Chopin Recital 2

Chopin Recital 2