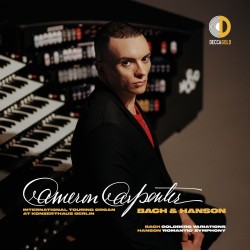

Bach: Goldberg Variations; Hanson: Romantic Symphony - Cameron Carpenter

Bach – Goldberg Variations; Hanson – Romantic Symphony

Bach – Goldberg Variations; Hanson – Romantic Symphony

Cameron Carpenter

Decca Gold (deccarecordsus.com/labels/decca-gold)

J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations have become ubiquitous in the classical music world, brought to popularity primarily through Glenn Gould’s debut recording in 1955. Originally written for harpsichord and published in 1741, this virtuosic masterwork has since been adapted for a wide range of instruments and ensembles, from piano to full orchestra. This recording features renowned American organist Cameron Carpenter performing his own transcription on the International Touring Organ, the American digital concert organ designed by Carpenter that travels from country to country with him on his tours.

What makes the organ such a unique instrument for the performance of the Goldberg Variations is the number of sounds that can be contrasted and combined by a single player, resulting in clear contrasts that amplify the linear complexities of Bach’s counterpoint. Where other instruments are limited by timbral similarities, the organ is capable of producing strikingly different sounds simultaneously, with one set of pipes sounding like a flute and another like an oboe, for example, creating a textural clarity that is almost impossible on any other single-player instrument.

But while the tonal variety of the organ is an indispensable asset, its lack of acoustic attack can be a challenging factor. The harpsichord is, perhaps, the most attack-heavy keyboard instrument in history, its sound almost entirely characterized by the plucking of a string and the sound’s subsequent, rapid decay. Conversely, the organ produces relatively little attack but can sustain pitches indefinitely, requiring deft use of articulation to produce the clarity required in Bach’s music.

As one of the world’s best orchestral organists, Carpenter manages both the pros and cons of the organ with an expert hand, applying his mastery of timbral variety and thoughtful articulation to bring the Goldberg Variations to life in a new and exciting way.

Carpenter reinforces his status as a master of orchestral performance with his own transcription of Howard Hanson’s Symphony No.2, the “Romantic,” demonstrating both his own stunning virtuosity and the capabilities of the International Touring Organ. This powerhouse performance is both unique and remarkable, and sheds light on a work that, while less well known than its recorded counterpart, is equally satisfying and impressive.