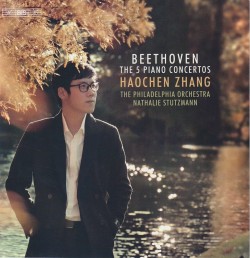

Beethoven – The Five Piano Concertos

Beethoven – The Five Piano Concertos

Haochen Zhang; Philadelphia Orchestra; Nathalie Stutzmann

BIS BIS-2581 SACD (bis.se/performers/zhang-haochen)

Having taken the classical piano world by storm when he first burst upon the scene in 2009 as the youngest pianist to ever receive a gold medal at the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, Haochen Zhang, now 32 with three releases under his belt, offers a fine follow-up recording here to his earlier Tchaikovsky and Prokofiev piano concertos. Once again recording for Naxos, Zhang performs Beethoven alongside the well-regarded Philadelphia Orchestra, the city in which the Chinese-born Zhang is currently based, under the direction of guest conductor Nathalie Stutzmann.

For any pianist, even one as accomplished as Zhang, to take on a complete program (spanning three discs) of Beethoven’s five piano concertos is yeoman’s work indeed. First there is the work of performing the pieces themselves (the study, nuance, technical challenge, among literally thousands of additional artistic decisions), plus the “work” of situating oneself into the canon of Beethoven interpreters (of which there are many and they are great), adding one’s name and vision onto the ever-growing corpus of versions and canonic contributions.

Nicholas Cook, writing in Music: A Very Short Introduction coins the phrase: “The Beethoven Effect” referring principally to the fact that Beethoven, freed from the obligation of compositional servitude to a church, a noble patron, or a feudal landlord was perhaps the first true musical “artist,” (differing here from trades or crafts person) who enjoyed a kind of self-awareness of his own greatness that not only traversed geography but the “boundaries of time and space.” Beethoven’s music was, as Cook suggests, “for the ages,” and, although difficult to know for certain, Beethoven knew it. Unlike Bach, who would use his own handwritten etudes as parchment paper to wrap lunches while taking a break from his teaching obligations at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, Beethoven did not view his music so ephemerally. As a result, offers Cook, composing after Beethoven was an exercise in hearing his historical and giant footsteps from behind.

With such grandiosity of intent and purpose came the grand compositional gestures that we now associate as hallmarks of Beethoven specifically, and the Romantic era more generally. And it is in these expansive signifiers, hugely encompassing of human emotion and offering a kind of bordered frame that tests the limits of any performer brave enough to tackle his repertoire, that Zhang excels. Where, for example, a less competent interpreter would use virtuosity as a proxy for expressiveness, Zhang’s performance here sounds as if there is another dimension in play where we do not just hear, as Hans Von Bulow established, the pianist abdicating one’s agency so audiences hear only the composer and not the performer, but rather a satisfying fusion that is equal parts Beethoven and Zhang.

Lastly, when we look at classical music history through the eyes of today, we often see an artificial bifurcation between composers and performers/improvisers. But Beethoven, in addition to being a composer, was apparently an extremely fine pianist, and, like the aforementioned Bach, improviser. And it is here as well where we hear Zhang contributing to the continuum of the pianist Beethoven, wrestling with, accepting and ultimately transcending this music with this fine recording that is sure to add much lustre to his impressive but still developing legacy.