Not many months go by without a new set of the Bach solo works for violin or cello appearing, and this month sees two new additions.

The American cellist Mike Block is a member of the Silkroad Ensemble and inventor of the Block Strap, an attachment that allows the cellist to stand and walk around while playing. His latest release, Step into the Void (Bright Shiny Things BSTC-0132 brightshiny.ninja), is a 3CD set featuring the Complete Bach Cello Suites with a live companion album featuring phonograph performance artist Barry Rothman.

The American cellist Mike Block is a member of the Silkroad Ensemble and inventor of the Block Strap, an attachment that allows the cellist to stand and walk around while playing. His latest release, Step into the Void (Bright Shiny Things BSTC-0132 brightshiny.ninja), is a 3CD set featuring the Complete Bach Cello Suites with a live companion album featuring phonograph performance artist Barry Rothman.

Normally with these releases the booklet notes mention a lifelong study of the works and an attempt to define a personal approach to the music before committing a performance to disc, but while Block admits to doing “the obligatory study” of various editions and recordings with the goal of creating his own consistent and historically informed interpretation, he now opts instead for spontaneity preferring to find different ways of playing them every time and not making too many performance decisions in advance, instead letting the feel of the audience and the acoustic space be his guide.

Certainly there’s a refreshing freedom and a sense of exploration in his beautiful playing here, a feeling of “let’s see where this goes” with delightful results. For this album he limited himself to two takes for each movement in order to “stay in the moment” and “play from the gut.” He also chose not to observe repeats in the dance movements (i.e. 30 of the 36 movements – all but the opening Preludes) so the two Cello Suite CDs are relatively short at about 37 and 50 minutes respectively.

The third CD, recorded live at a sold-out show a few days after the recording of the Bach Suites, grew from an earlier free-improvisation performance with Rothman. Block asked if they could play a completely improvised live duo concert with him using only material from the Bach Cello Suites. The results are quite fascinating – with less LP interaction than you might expect – although probably not to everyone’s taste.

A bonus track of Block’s own pizzicato Prelude to a Dream completes a quite special set.

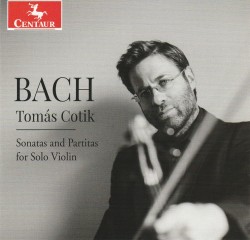

Violinist Tomás Cotik’s brilliant recording of the Bach Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (Centaur CRC 3755/3756 tomascotik.com) is released this month to mark the 300th anniversary of their composition.

Violinist Tomás Cotik’s brilliant recording of the Bach Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (Centaur CRC 3755/3756 tomascotik.com) is released this month to mark the 300th anniversary of their composition.

The promo copy came with an extremely detailed 32-page booklet which appears to be a collection of the ten brief articles Cotik wrote for The Strad magazine last year, and which can be accessed through his website at tomascotik.com. Just about every approach to performance issues is addressed – everything from the physical instrument and bow through early treatises and editions, to the implementation of slurs, dynamics, chords, vibrato, pitch, ornaments, trills and much more.

Cotik uses a modern violin – albeit with softer and more resonant strings than usual – with a Baroque bow, which he feels offers more expressive potential, subtle nuances and transparent textures and allows for “a lighter sound, quicker, more flowing tempi, and lively articulations.” That’s exactly what we get here, with Cotik producing a smooth but bright sound with a lightness and agility that is quite breathtaking and never in any danger of becoming heavy-handed or over-stressed. Slower tempos are relaxed but never allowed to drag; faster tempos are dazzlingly brilliant, with faultless intonation.

The result is a very personal and distinctive sound and style, with even the massive D-minor Chaconne never approaching the heavy and ponderous tones of some recordings.

Interestingly, Cotik repeatedly returns in his writings to the need not to be hide-bound by rules of interpretation; studying the music is just the starting point of a journey where interpretation changes along the way. He admits that many of those challenges “can ultimately be solved only by each of you in performance – not to mention differently every time” (my italics).

And perhaps, as with Mike Block, that’s the secret here; never settle for one consistent interpretation and always let curiosity be a constant inspiration. If Tomás Cotik ever revisits these works on record it will be fascinating to hear the results, but it’s hard to see how they could be better than this.

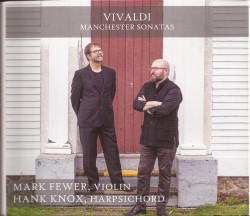

Manchester isn’t exactly a city you associate with Baroque violin sonatas, but it’s front and centre in Vivaldi – Manchester Sonatas, an excellent new 2CD set from violinist Mark Fewer and harpsichordist Hank Knox (Leaf Music LM229 leaf-music.ca).

Manchester isn’t exactly a city you associate with Baroque violin sonatas, but it’s front and centre in Vivaldi – Manchester Sonatas, an excellent new 2CD set from violinist Mark Fewer and harpsichordist Hank Knox (Leaf Music LM229 leaf-music.ca).

The manuscripts for this collection of 12 works by Antonio Vivaldi originated in the private collection of Vivaldi’s contemporary Cardinal Ottoboni, passing through several owners (including Handel’s Messiah librettist Charles Jennens) before being purchased by the Manchester Public Library in 1964. Even so, they were only discovered in Manchester’s Henry Watson Music Library in 1973 by musicologist Michael Talbot.

Apparently dating from the 1716-1717 period the collection contains only four sonatas that were completely new – Nos. 5, 10, 11 and 12 – the remaining eight known to exist in earlier sources although reworked in numerous ways here to fit the duo genre. The violin part, while quite detailed for the period, still leaves room for embellishment by the performer; the harpsichord part, meanwhile, does not even feature a figured bass line most of the time, so Knox has full rein when it comes to realizing the accompaniment.

Fewer’s playing is bright, assured and technically brilliant, with Knox supplying a rich accompaniment that focuses more on harmonic support than contrapuntal interplay of melodic voices. The sonatas themselves are highly entertaining and inventive, featuring less of the usual Vivaldi arpeggios, scales and sequences than you might expect. The fast movements in particular are quite exhilarating.

There are no track timings, but the two CDs run to 68 and 63 minutes respectively.

Listen to 'Vivaldi: Manchester Sonatas' Now in the Listening Room

There are quite lovely performances of the Beethoven Violin Concerto & Romances on a new CD featuring Lena Neudauer and the Cappella Aquileia under Marcus Bosch (cpo 777 559-2 naxosdirect.com).

There are quite lovely performances of the Beethoven Violin Concerto & Romances on a new CD featuring Lena Neudauer and the Cappella Aquileia under Marcus Bosch (cpo 777 559-2 naxosdirect.com).

The ensemble, founded by Bosch in 2011 as the orchestra for the Heidenheim Opera Festival, draws top-level musicians from across Germany and beyond, with its size based on the original chamber-symphony proportions of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. There’s a resulting clarity and transparency to the playing that makes the concerto in particular less heavy than in many performances, the quite dry and short opening timpani strokes setting the stage for an idiomatic performance that never lacks emotional depth. The timpani also features in the first movement cadenza, Neudauer drawing on Beethoven’s own cadenza for his piano transcription of the concerto. The Romances in G Major Op.40 and F Major Op.50 have the same delightful feeling of light and clarity without ever sounding lightweight.

Neudauer’s playing throughout is exemplary and stylistically beautifully judged – hardly surprising given her admission that it was Thomas Zehetmair’s recording with Franz Bruggen’s Orchestra of the 18th Century that was the key to her understanding the concerto. Bosch provides sympathetic support on an outstanding CD.

I can’t remember when I last heard the Schoenberg Violin Concerto, which made Schoenberg Brahms Violin Concertos, the latest CD from the outstanding violinist Jack Liebeck, even more welcome. Andrew Gourlay conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra (Orchid Classics ORC100129 orchidclassics.com).

I can’t remember when I last heard the Schoenberg Violin Concerto, which made Schoenberg Brahms Violin Concertos, the latest CD from the outstanding violinist Jack Liebeck, even more welcome. Andrew Gourlay conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra (Orchid Classics ORC100129 orchidclassics.com).

The album, celebrating Liebeck’s upcoming 40th birthday, is a deeply personal one for him, described in the booklet notes as a “visceral and passionate portrait of two major violin concertos, emotionally drawing from the experience of his grandfather and honouring the many members of his family who perished during the Holocaust.” More than three dozen of Liebeck’s mother’s Dutch relatives died. Liebeck’s grandfather, Walter Liebeck, was a decent amateur violinist; a student in Germany when Hitler came to power in 1933, he left for South Africa the following year. The Brahms was his favourite concerto.

Schoenberg himself left Germany in 1933 for the United States. His 1936 concerto marked a return to atonality after a relatively tonal period, but despite its 12-tone basis and the composer’s own description of it – “extremely difficult, just as much for the head as for the hands” – it’s a quite stunning work that is emotionally clearly from the heart, and that really deserves to be much more prominent in the mainstream violin concerto repertoire.

Liebeck displays all of his usual qualities – clarity and strength, brilliance of tone, impeccable technique, faultless phrasing and interpretation – in immensely satisfying performances of two quite different but perfectly-paired works. Gourlay and the BBCSO are quite outstanding partners.

Violinist Piotr Plawner is the soloist on Philip Glass American Four Seasons, a new CD in the Naxos American Classics series that features the composer’s Violin Concerto No.2, with Philippe Bach conducting the Berner Kammerorchester, and the Sonata for Violin and Piano with Gerardo Vila (Naxos 8.559865 naxos.com).

Violinist Piotr Plawner is the soloist on Philip Glass American Four Seasons, a new CD in the Naxos American Classics series that features the composer’s Violin Concerto No.2, with Philippe Bach conducting the Berner Kammerorchester, and the Sonata for Violin and Piano with Gerardo Vila (Naxos 8.559865 naxos.com).

It was violinist Robert McDuffie who, enamoured with Glass’ Violin Concerto No.1, suggested the idea of an American Four Seasons as a sequel that could be programmed with the Vivaldi classic. Jointly commissioned by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the new work was premiered by McDuffie and the TSO under Peter Oundjian in Toronto in December 2009.

Scored for strings and synthesizer (set for harpsichord sound but not used as a continuo) the four movements were deliberately left untitled by Glass, inviting listeners to decide for themselves which movement best depicts each season. A solo violin Prologue and three numbered Songs between the movements – which Glass felt could be extracted as a separate work for solo violin – act as cadenzas. Several Glass characteristics – arpeggios and sequences, for instance – provide a link with the Vivaldi era, but in a strongly tonal work the sound is unmistakably Glass.

Much the same can be said of the Violin Sonata, apparently written with youthful memories of the violin sonatas of Brahms, Fauré and Franck in mind, but again unmistakably Glass, with a show-stopping third movement.

Top-notch performances all round make for a highly enjoyable disc.

The Fitzwilliam String Quartet continues the celebration of its 50th anniversary with another outstanding CD following the Shostakovich Three Last Quartets reviewed here last month. This time it’s Franz Schubert String Quartets – those in A Minor D804 (often called the “Rosamunde”) and the monumental D Minor D810 “Death and the Maiden” – performed on period instruments with Viennese gut strings (Divine Art dda 25197 naxosdirect.com).

The Fitzwilliam String Quartet continues the celebration of its 50th anniversary with another outstanding CD following the Shostakovich Three Last Quartets reviewed here last month. This time it’s Franz Schubert String Quartets – those in A Minor D804 (often called the “Rosamunde”) and the monumental D Minor D810 “Death and the Maiden” – performed on period instruments with Viennese gut strings (Divine Art dda 25197 naxosdirect.com).

Violist Alan George’s outstanding booklet notes once again add immensely to our understanding of these almost symphonic works and the performance questions they raise – questions superbly answered by the FSQ. Vibrato – if used at all – functions as an expressive device, emphasising accents, increasing intensity and employed as decoration or ornamentation. Similarly, historically informed use of the bow, the treatment of the abundant dynamic markings and the approach to choice of tempo were all subjects with which the ensemble took great pains.

The resulting performances consequently have a feeling of authenticity that is quite remarkable and perfectly exploits the emotional range of these visionary works. In spite of knowing and coaching the Death and the Maiden quartet for many years, the Fitzwilliam only added it to their own repertoire eight years ago, although it sounds as if they’ve been performing it all their lives; the wild finale, says Alan George, “still leaves us all physically and emotionally shaking.”