Teachers! Stand Out From The Crowd!

Even with opportunities for unguided self-teaching proliferating through the internet, music remains largely an oral tradition, handed down directly from teacher to student and consisting largely of showing students how to teach themselves, which is done by what is usually called practising, and which I like to call guided self-teaching.

Even with opportunities for unguided self-teaching proliferating through the internet, music remains largely an oral tradition, handed down directly from teacher to student and consisting largely of showing students how to teach themselves, which is done by what is usually called practising, and which I like to call guided self-teaching.

When a student studies music by taking lessons with a teacher, the effectiveness of the lessons – gauged by how well the student progresses – depends on two things: the receptivity of the student and his/her ability to attempt and then to master the things that the teacher recommends; and the teacher’s ability to assess what the student is able to do and not do, and to recommend techniques and skills to practise in the time between lessons. The fit between teacher and student therefore becomes a more important criterion than anything else in determining whether learning music becomes a rewarding experience.

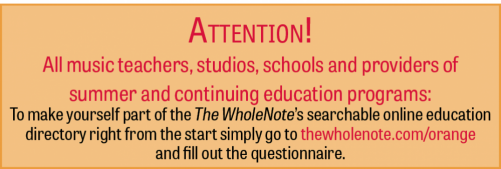

With this month’s launch of The WholeNote’s online ORANGE PAGES searchable directory we are taking the first steps towards helping music students and would-be students find that perfect match. Already over 145 teachers, community music schools and summer music programs have filled out the online questionnaire that enables them to be found through our ORANGE PAGES, with more signing up every day.

All that being said, we are under no illusions that we have suddenly become the only, or even the primary way for this crucial matchmaking to take place. The search for and finding of a musical mentor comes in many forms, as the following three short descriptions of existing education-related musical resources show.

Ontario Registered Music Teachers Association: The Ontario Registered Music Teachers Association (ORMTA) was established in 1936 to establish high standards of private music instruction in Ontario. I spoke to Etobicoke-Mississauga branch president Virginia Taylor, about ORMTA’s contribution to music education: “ORMTA,” she told me, “provides a superior level of teaching, which ensures parents and students alike of a studio experience that is of the highest quality.” Membership requires not only a good musical education but also evidence of effective teaching. In other words, members must have done some teaching before becoming members of ORMTA. Once a member, however, “ORMTA gives a teacher the advantage of continuing education and learning by attending the many workshops, master classes and conferences offered through the organization.”

ORMTA also offers student assessments, by which, Virginia told me “students are able to have their work audited by another professional, which…gives [them] an unbiased opinion of their performance.”

She also raised another very interesting benefit. Anyone who has taught, whether in the school system or privately, has to be very aware that one of the occupational hazards of the business is the lack of contact with one’s peers. ORMTA, Virginia pointed out, in organizing workshops and conferences, also provides camaraderie through contact with other music teachers, and also “a forum for bouncing off teaching questions.”

ORMTA encourages non-members to join. Everything you need to know about joining the organization is on their website. “Our workshops,” she told me “are open to non-members, and we encourage teachers who are not ORMTA members to participate in them. ORMTA has given my teaching life excellence and much meaning, and also my personal life, as I have colleagues with whom I am constantly in touch, andwho share the same life that I do. Their ideas and advice I greatly treasure.”

Mooredale Youth Orchestras: An opportunity available to students once they are at grade four level and beyond, is the three Mooredale youth orchestras, which were started back in 1986 by the late Kristine Bogyo so that her two sons, one of whom played the violin, the other, the cello, would be able to play in an orchestra.

I spoke recently to William Rowson, who became the conductor of the Junior and Senior Orchestras in 2008. We began by talking about the benefits of participating in the Mooredale program. Although some of the orchestra’s alumni, he told me, become professional musicians, it is not so much about producing professionals as it is about realizing what is possible. “I challenge them, and at first they are overwhelmed, but then they go on to work out how and what they need to practise and how to make use of their time.” Young people, he said, “are up for challenges, they want to be great, and if you show them what is possible and how to achieve it, they will achieve.”

One of the challenges Rowson brings is to treat his orchestra members like professionals in the sense that he expects them to come to rehearsals with their parts learned; it can be necessary to work on certain passages with only one section. To keep the rehearsal flowing and to keep the other sections actively involved he asks them to listen, to see if they can hear how it could be better, to hear where the phrases are going and to be able to articulate the character of the piece.

While much of the orchestras’ repertoire is standard – everything from early Haydn to Warlock’s Capriole Suite – it does also work in a certain amount of contemporary music. Rowson, who has a PhD in composition, has written works for his orchestras, and contemporary composers are invited to bring works for the orchestras to read through.

Regardless of what music the orchestras are working on, the aim is always to give the experience to the members of working through difficulty to make things possible.

Conference of Independent Schools of Ontario:The Conference of Independent Schools of Ontario (CIS Ontario) is an association of schools which are not publicly funded and which meet a number of rigorous criteria. I chatted with Jan Campbell, the executive director of the association about the place of music in the independent schools. While there is no common consensus or policy about the place of music in education, there is, she told me, huge value placed on student programs outside of the academic programs.

One of the products of this commitment will be the Conference of Independent Schools Music Festival at Roy Thomson Hall on April 13. Over 40 of the 44 member schools will be participating in this major collaborative effort, each having prepared for months in advance to achieve a high level of musicianship and artistry. Choirs, orchestras and bands will all perform, and the grand finale will be a massed choir and orchestra spectacular.

Just as with the Mooredale Orchestras, this event provides great motivation and inspiration for students and teachers alike as well as an opportunity to meet many new people and colleagues.

The event is close to sold out but tickets will be available for the dress rehearsal. Please see the ad on page 69 for details.