That such groups did not exist wasn’t an impediment to these young musicians; they gathered instruments, formed an ensemble and organized the first Western concerts of purely percussion music such as Cage’s own Credo in US (1942), and the First, Second and Third Construction in Metal (1939–42), and Harrison’s Fifth Simfony and Concerto No.1 (both 1939). Numerous composers and performers have since taken up the cause of percussion music in subsequent decades, including the iconoclastic American composer, music theorist and instrument inventor Harry Partch.

That such groups did not exist wasn’t an impediment to these young musicians; they gathered instruments, formed an ensemble and organized the first Western concerts of purely percussion music such as Cage’s own Credo in US (1942), and the First, Second and Third Construction in Metal (1939–42), and Harrison’s Fifth Simfony and Concerto No.1 (both 1939). Numerous composers and performers have since taken up the cause of percussion music in subsequent decades, including the iconoclastic American composer, music theorist and instrument inventor Harry Partch.

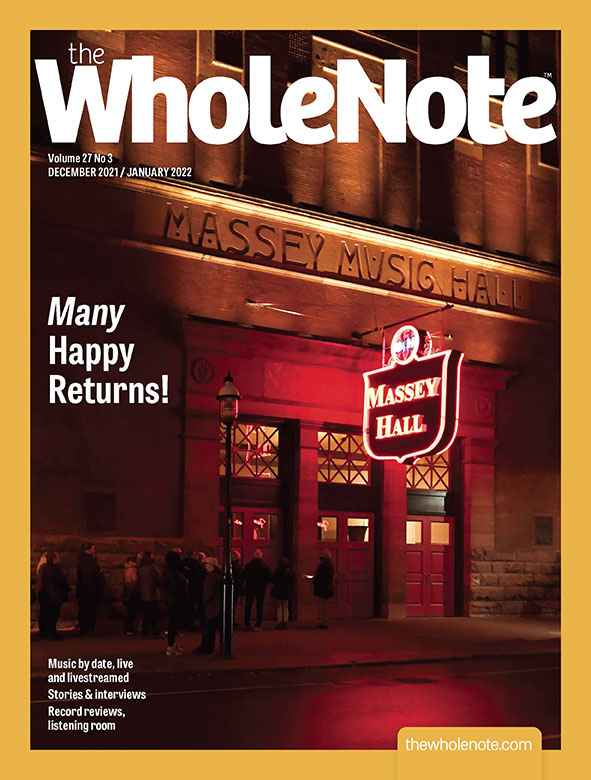

So, how much have things changed? Well, last week (on February 24, 2011), I attended a Soundstreams produced concert at Koerner Hall by Les Percussions de Strasbourg, the grandfather of modern European percussion groups, at which its current team of six percussionists marked a remarkable 50 years of performances by the ensemble. This week, solo percussionist extraordinaire Dame Evelyn Glennie is the featured soloist in the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s March 2 opening concert of the New Creations Festival at Roy Thomson Hall. March also brings us auspicious anniversary concerts by two other percussion groups: Nexus turning 40, and Kodo Drummers turning 30. If that weren’t enough, the international percussion service organization Percussive Arts Society (PAS), with over 8,500 members, is marking its 50th year of operation.

With all these notable percussion ensembles beating the anniversary drum in a spate of Toronto concerts, it feels as if percussion ensemble music is coming of age. In a recent interview I asked Dame Evelyn Glennie, one of today’s most widely admired solo classical percussionists, about this apparent convergence.

“It is very encouraging,” she replied. “It is no longer unusual for orchestras and concert promoters to put on percussion concerts as part of their normal season. In fact it is more unusual not to find something ‘percussive’ listed nowadays. The ensembles you have listed have each had strong identities and evolved during times when there was real curiosity about what they were performing and how it was performed. They have managed to sustain that high level of performance whilst developing their brand.”

In her Toronto concert, Glennie and the TSO will be presenting the local premiere of The Shaman, by Ottawa native Vincent Ho, currently composer-in-residence with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. “The Shaman is a very beautiful and powerful work,” notes Glennie. “The composer creates excellent balance between organic drumming whilst always keeping the music line, and real suspense through a simple delicate and passionate melody. Vincent Ho has really understood percussion well and created a roller-coaster ride of emotions.”

Glennie is a remarkable, multi-talented individual. She may well be the first person in Western musical history to successfully create and sustain a full-time career as a solo classical percussionist. In her primary profession she has constantly striven to redefine the goals and expectations of percussion music – and also performs with orchestras on the Great Highland Bagpipes. Among many other interests she is active as a motivational speaker, composer, best-selling author (her autobiography: Good Vibrations), educator, TV personality and jewellery designer. Obviously also in good physical shape, last December she ascended Mount Kilimanjaro for the charity Able Child Africa.

Back to her music: Glennie records and tours widely, giving more than 100 performances a year worldwide. Performing with leading orchestras she has been featured on 26 solo recordings. Her first CD, Bartók’s important work Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, won her a Grammy in 1988. A further two Grammy nominations followed, one of which she won for a collaboration with the American banjo virtuoso Bela Fleck.

Asked about the particular significance of the current stage of her solo career she countered: “Each stage of my career has been significant because I am treading new territory most of the time. The period I am experiencing now is allowing me to see the impact of the work during the past 20 years – the belief that a solo percussion career is absolutely sustainable and should not/cannot be challenged ever again.”

Her many local fans will no doubt pack Roy Thomson Hall March 2 to experience her signature brand of percussive magic. But from a global perspective, some would argue (I among them) that when it comes to the role of percussion, the Western concert tradition is still playing catch-up with much of the world. As Glennie puts it: “Our western classical music or indeed much of our folk music has not had percussion as the backbone to its existence, unlike the music of Africa, Far East, South America, etc.” where percussion instruments and entire ensembles have enjoyed pride of place as far back as we can trace. In China large orchestras including tuned bronze bells and stone chimes were part of aristocratic entertainments as far back as the 5th century BCE. In S.E. Asia, percussion-rich ensembles both large and small still feature prominently in the musical lives of several cultures. The Indonesian gamelan and Japanese drumming traditions offer compelling arguments on this point, and not just in their Asia homes either. In the past three decades their traditions have set roots here in Canada, from St. John’s to Vancouver.

The Japanese group Kodo, sometimes referred to as Kodo Drummers, is a good example of a percussion ensemble reflecting its own regional Asian folk roots, yet also totally at home on the international road. Kodo’s March 11 show at the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts is only one of 29 concerts in its present North American tour. A veritable touring juggernaut, to date Kodo has logged over 3,300 performances on five continents. That measure alone makes it arguably the most successful international percussion ensemble group ever. Their goal is to reach as many people as possible, yet they remain firmed rooted in the local village community on diminutive Japanese Sado island. On their official website, however, they take care to stress that while “Kodo is not a preservation society involved exclusively in the passing down of local Sado traditions,” their performances are based upon traditional folk arts, learned from people throughout Japan’s many regions. Kodo’s intention is not simply to replicate these living performing arts, however. Their goal is rather to rearrange them for the stage in an attempt to “capture their universal spirit and energy as they filter through our bodies.”

I interviewed former Kodo apprentice Kiyoshi Nagata, the artistic director of Toronto’s own taiko group Nagata Shachu, about Kodo. “Kodo tours internationally under the banner One Earth Tour” Nagata notes. “This reflects the group’s philosophy. In touring they believe the boundaries of their tiny island village are culturally expanded to embrace the people of the globe.”

“The origins of Kodo lie with a few groups formed by young Japanese in the post WW II era,” says Nagata. “Disillusioned by what they saw as the westernization of Japanese culture they wanted to revitalize it by returning to folk traditions, as well as to Japanese spiritual and physical values and disciplines.” The skill and discipline of playing taiko, originally part of matsuri (festival) music, was part of this effort.

Although the main focus of Kodo’s performances is taiko (Japanese name for drum), it is notable that other traditional Japanese musical instruments such as fue (transverse bamboo flute) and shamisen (plucked lute) are used on stage as is traditional dance and vocal performance.

How did Kodo take a Japanese drum-heavy festival music and parlay it into a major act on the world’s main stages? Part of the answer lies in Kodo’s rigorous physical training, as well as the dance and song elements added to the power, precision and excitement of the taiko ensemble. Another part is the compelling compositions contributed by Maki Ishii and Shinichiro Ikebe, and also by the Kabuki (a form of traditional Japanese theatre) orchestra musicians Roetsu Tosha and Kiyohiko Senba. Compositions by the jazz pianist Yousuke Yamashita also add to this rich mix. Original works by Kodo members, based on Japanese folk forms, complete their creative team portrait.

Kodo’s iconic huge drums played by powerfully toned males in loincloths and headbands have become a commonplace icon in mainstream media. Years ago I attended an impressive Kodo concert at Massey Hall. I saw first hand the mental and physical culture required to produce their music. (I’ll admit I wondered about the loincloths.)

I asked Kiyoshi Nagata: “It’s part of Kodo’s return to old Japanese tradition,” he replied with a smile. “The loincloth was everyday wear for Japanese farmers and Sumo wrestlers, for example. It’s also appealing to audiences everywhere I think. There’s another aspect too. In Japanese culture the cultivation and display of the human body is important as an expression, a demonstration, of the learning and discipline one has acquired through diligent work.”

And what about the quasi-ritual aspect some see in Kodo concerts? “Actually the group’s spiritually goes hand in hand with their performances. This comes through in the physicality of the drumming, in the training discipline and in the stamina required to perform on the massive drums they use, some played with mallets the size of baseball bats. The taiko has a long history in villages and temples as an instrument used to communicate with the Shinto gods, a custom which is still widely maintained. Kodo taught me to approach the drum with full body, mind and spirit.”

Returning to my exchange with Dame Evelyn Glennie and her reflections on the development of Western classical percussion music, at one point in the exchange she noted: “The progression of percussion has happened in a totally organic way in the West and we should respect that. The types and quality of instruments have greatly improved over the last century allowing greater depth of emotion and the possibility to physically project better in our big performing spaces... The physical negotiation of playing the instruments has allowed real specialists to evolve in many areas of playing such as timpani, marimba, vibraphone, drumkit, etc., thus feeding composers with [performers possessing] greater skill in exploring the physical and emotional content drawn from their instruments.”

Returning to my exchange with Dame Evelyn Glennie and her reflections on the development of Western classical percussion music, at one point in the exchange she noted: “The progression of percussion has happened in a totally organic way in the West and we should respect that. The types and quality of instruments have greatly improved over the last century allowing greater depth of emotion and the possibility to physically project better in our big performing spaces... The physical negotiation of playing the instruments has allowed real specialists to evolve in many areas of playing such as timpani, marimba, vibraphone, drumkit, etc., thus feeding composers with [performers possessing] greater skill in exploring the physical and emotional content drawn from their instruments.”

While Glennie draws on her own career of commissioning and premiering over 160 compositions for this insight, the pioneer Canadian percussion group Nexus could well be the dictionary definition of what she talks about. Along with Les Percussions de Strasbourg, Nexus occupies the front rank of percussion ensembles, paving the way for many others who have followed. These virtuoso musicans have trekked intrepidly ever since their 1971 premiere, and were notably the first Western percussion group to perform in the People’s Republic of China. Nexus is particularly renowned for their improvisational skills and their interpretations of 20th century avant guard masterworks alongside music from other global cultures.

With its March 12 Glenn Gould Studio concert marking 40 years of music making, dare one ask if Nexus shows signs of slowing down? Reached on tour in Syracuse, NY, founding Nexus member Bob Becker commented, “Mostly at our age we simply hope to continue to play music! Seriously, the Toru Takemitsu concerto From Me Flows What You Call Time, written for us and symphony orchestra, is one that still offers challenges and room for exploration.”

Premiered at Carnegie Hall’s centennial celebration in 1990, this work remains one of Nexus’ grandest calling cards, a profound musical experience I had the pleasure of witnessing at a TSO season concert some time ago. During its long career, Nexus has gone on to create a deep and broad body of music performance, education, recordings and an illustrious history of collaborations and commissions. Inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame in 1999, over the years they have released a remarkable total of 22 CDs including the Juno-nominated Drumtalker. Increasingly their “book” forms the core repertoire for percussion ensembles around the world.

I asked why most of the group’s members, originally American, chose to settle in Toronto. “There was a special atmosphere in Toronto the early to mid 70s,” said Becker. “Both the musicians and audience then seemed to embrace sonic exploration and free improvisation, plus there was freedom to collaborate with other artists such as painters and dancers.”

I asked why most of the group’s members, originally American, chose to settle in Toronto. “There was a special atmosphere in Toronto the early to mid 70s,” said Becker. “Both the musicians and audience then seemed to embrace sonic exploration and free improvisation, plus there was freedom to collaborate with other artists such as painters and dancers.”

After four decades however, let’s face it, the road does take its toll – even for the most passionate sonic pilgrim. I wondered if Nexus plans to reduce the vast number of instruments they use to set up on the stage for each performance.

“Yes, perhaps we’re refining our selection,” Becker comments. “We can’t reduce our instrumentation drastically, however, since we require our own custom instruments such as the large marimbas and special xylophones I use. We still tour with a loaded 16-foot truck! Another reason is that percussion instruments are less standardized than most others, less than strings or winds for example. Each cymbal has a unique sound profile – that is at the core of what we offer our audiences.”

“We’ve got a few new exciting works coming up such as The Crystal Cabinet by (Nexus regular) Bill Cahn which we’ll premiere at our Glenn Gould Studio concert. Also for a number of years we’ve been inviting percussionists such as Ryan Scott to play with us. At our upcoming Glenn Gould Studio concert we’re excited to have TSO principal timpanist David Kent join us.”

Nexus’s March concert also features Cinq Chansons pour Percussion (1980) by Canadian composer Claude Vivier (1948-1983). It is one of several works influenced by Vivier’s trip to Bali, Indonesia, and the music of the gamelan, a percussion-rich ensemble in which tuned metal, wood and bamboo percussion instruments are featured.

And speaking of gamelan music, Canada’s first group to play it, the eight member Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan (ECCG) (of which I am a member) is now in its 28th season. As noted in my World View column later in this issue, ECCG performs in concert with the Via Salzburg Chamber Orchestra on March 24 and 25 at the Glenn Gould Studio. Many ECCG musicians have not only studied with members of Nexus but have also performed and toured with Nexus itself. Cementing that connection, Nexus co-founder John Wyre composed several significant works for ECCG. Links go back even further however to two of the “founding fathers” of American percussion music mentioned earlier. ECCG commissioned and premiered works by both John Cage (Haikai, 1986) and Lou Harrison (Ibu Trish, 1989) toward the ends of their illustrious careers.

Percussion may have taken a thousand years to acquire western classical credibility. In the current climate of confluence, continuity and change, and under the stewardship of practitioners such as Glennie, Kodo and Nexus, can we safely say it has arrived?