The More It All Changes...

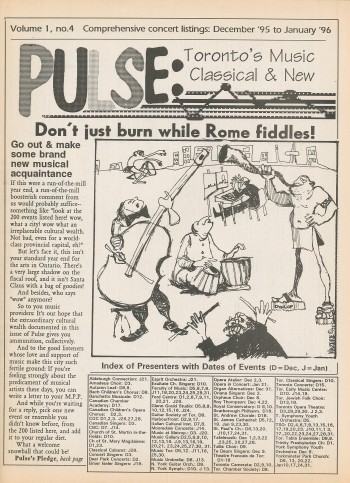

Those of you who have followed this publication over the years know that without the existence of Toronto’s Kensington Market The WholeNote would likely never have come into being. For one thing, this publication started out 25 years ago as a classical music column (called “Pulse”) written by one of our founders, Allan Pulker, and appearing in a monthly neighbourhood newspaper, the Kensington Market Drum, founded and run by yours truly and The WholeNote’s operations manager Jack Buell.

Back then, Pulker had the crazy idea that there was enough ongoing musical activity of the classical kind going on within easy bicycling distance of Kensington Market to warrant not only a regular column but also a solid half page or so of listings. He came back with a plastic bag of brochures and flyers to prove it. Perlman and Buell were quixotic enough to agree, and the windmills have been whirling ever since.

Kensington is still our home (for going on 35 years now). People say things like “Oh you live in Kensington? - I haven’t been there for years but I was there last weekend. It sure has changed a lot …”

Funny thing is, I find myself getting all knee-jerk defensive when they say it, irrespective of whether it sounds as though they are suggesting it has changed for the better or for the worse! Things we count on are somehow not supposed to change, even though as individuals we are changing all the time.

So how does this apply to The WholeNote and our two decades of championing live music performance? For one thing, our magazine is evidence, for anyone who cares to look, of the ways in which our region’s live performance ethos is in a state of change. Because we have managed to keep our daily concert listings free, presenters get one whether or not they can afford to buy an ad. And because certain supporters of the magazine still harvest listings in plastic bags and bring them to us, musicians sometimes get free listings, even if they didn’t bother to send them in.

Our listings tell us all kinds of things: That there are more performances all the time in what, even a few years ago, would have been described as “non-traditional concert venues.” That there are, today, very few places that cannot be turned into viable performance venues by opportunistic and/or creative musicians and presenters. And that, increasingly, many people want to listen to live music in places that resonate with them whether or not those places work for the music and the performers.

On the other hand, they also tell us that so-called traditional concert venues, increasingly pronounced dead (or else shrines for music that is dead), remain astonishingly resilient. All the more astonishing given the ease with which technology today enables people to privatize their personal musical experiences, to use music to turn public spaces into private ones.

There are still many thousands of concertgoers who want their listening to happen in places where other people have gathered to listen to the same things, and where the listening is the point.

So we have among our readers large numbers of existing audience members who make regular concert-going pilgrimages to the music. And we have large numbers of potential audience members who believe that music makers should come to them with this music so they can sample it on their own terms. Or at the very least that it should happen in places in which they can feel at ease.

So, we have the example of Tafelmusik giving beautiful traditional concerts along with programs that push the boundaries of the traditional concert form, all in Jeanne Lamon Hall. And we also have them offering “Haus Musik” in the Queen West Great Hall – immersive evenings of baroque and DJ music, imagery, and dance, side by side.

Or, another recent example: Opera Atelier took a program called “Harmonia Sacra” (February 15) into the vaulted elegance of the ROM’s Samuel Hall Currelly Gallery, featuring a consort of early music players, soprano, baritone and three costumed Baroque ballet dancers; and threw in the bonus of a brand new performance piece for dancer and solo violin (Opera Atelier’s first Canadian commission – Inception) composed and performed by violinist Edwin Huizinga, with contemporary choreography by dancer Tyler Gledhill. It all became an illustration, perfectly (and beyond words) of how the underpinnings of what we call Baroque are alive and well today: sacred still meets profane; scored/choreographed still meets improvised; servant of the muse meets rock star.

What this all has to do with Kensington Market is that when the two broad categories of music lovers described above collide, as they must if our art is to survive, the lesson of the Market is that rough-and-ready cheerful resilience is what keeps you going. You’ll still be in eat-drink-and-be merry mode long after some others if you can accept that to stay alive, music-making, and the way it is presented, must continue to change – that change is the only constant.

Metaphorically, our musical streets bustle with grannies and children, homeless people and hipsters, wheelchairs, skateboards, and trick bikes, every kind of music and the languages of every nation. If you are lucky, in the middle of it all will be a circle of people standing around a musician playing the solo part to Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, hearing the whole orchestra in his head. And the audience around him, drawn from every imaginable category of market goers and music lovers, yourself included, will all be choosing to listen in an elective silence as beautiful as any concert hall. And no-one will shush the child who starts to sing along.

publisher@thewholenote.com