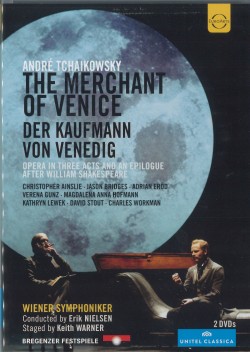

André Tchaikowsky – The Merchant of Venice - Ainslie; Bridges; Eröd; Gunz; Hofmann; Lewek; Stout; Workman; Wiener Symphoniker; Erik Nielsen

André Tchaikowsky – The Merchant of Venice

André Tchaikowsky – The Merchant of Venice

Ainslie; Bridges; Eröd; Gunz; Hofmann; Lewek; Stout; Workman; Wiener Symphoniker; Erik Nielsen

Unitel Classica 2072708

Re-discovery of a forgotten opera usually happens to obscure Baroque or Bel Canto masterpieces, which for unfathomable reasons have been gathering dust in some musty old library. More often than not, they enter standard repertoire for a brief period of revival, only to be forgotten again. Let’s hope that fate will not befall The Merchant of Venice – an opera 30 years out of its time. Nearly produced by the English National Opera in 1984 two years after the composer’s death, this opera finally received its due at the 2013 Bregenz Festival. The Festival’s artistic director, David Pountney, is a champion of forgotten composers and André Tchaikowsky, born Robert Andrzej Krauthammer in Poland, is definitely well deserving of such re-discovery.

Survivor of the Warsaw ghetto (which he escaped with an assumed “Christian” name of Andrzej Czajkowski on his fake papers) and the communist rule, Tchaikowsky was an acclaimed pianist. He placed amongst the finalists of the 1955 Chopin Piano Competition and 1956 Queen Elisabeth of Belgium Competition. Despite those early accolades, he decided to dedicate himself to composition. His output, if not huge, is thoroughly engrossing; alas Merchant is the only opera. And what an opera – there is no doubting its dramatic bona-fides: Tchaikowsky makes his own mark by imbuing Antonio with gay yearnings, absent in Shakespeare, and scoring the role for a countertenor. The Bregenz production casts Christopher Ainslie in that role, against the remarkable Adrian Eröd as Shylock.

As a final irony, the composer got to centre stage before his work did – he willed his skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company to be used in Hamlet as a prop. That acclaimed 2008 production, filmed by the BBC, featured David Tennant as the brooding prince and André Tchaikowsky’s skull as Yorick.