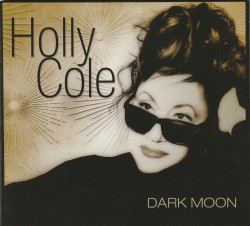

Dark Moon - Holly Cole

Dark Moon

Dark Moon

Holly Cole

Rumpus Room Records 0246557815 (umusic.ca/products/dark-moon)

Gifted chanteuse Holly Cole has just released her 13th studio album – a project that promises to be one of her most notable musical offerings to date. Cole serves as producer here and has also assembled a stellar coterie of musical colleagues that includes Aaron Davis on piano, George Koller on bass, Davide DiRenzo on drums, Johnny Johnson on sax as well as eminent guitarist Kevin Breit, harmonicist Howard Levy (famed member of Béla Fleck and the Flecktones), and the Nashville-inspired harmonic stylings of the Good Lovelies.

There are 11 exquisitely produced and performed tracks here, including compositions from Irving Berlin, Johnny Mercer, Bert Bacharach, Henry Mancini and Peggy Lee – all presented on a tasty platter of originality, and the highest musicianship. Steppin’ Out With My Baby is voiced at the bottom of her contralto register and supported by sweeping arco bass lines from Koller; Cole imbues this classic with a languid, contemporary eroticism. Moon River is performed with honesty and pure melodic integrity, while soulful and facile work from Davis is the icing on the cake.

Another shining gem is the moving, re-imagining of Bacharach and David’s Message to Michael. The forthright arrangement and Breit’s guitar contribution propel this Brill Building hit into a contemporary anthem of loss and longing. The rarely performed title track is a deft odyssey into Southern Swing motifs, replete with appropriate guitar support from Breit as well as vocal harmonies from the Lovelies that harken back to the incomparable Boswell Sisters. Cole’s take on the classic, Walk Away Renée is another triumph, as well as a fine piano/vocal duet featuring sublime intonation, communication and creative entanglement from Cole and Davis.