EDITOR’S CORNER - June 2011

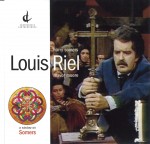

It is fitting that the first DVD release by the Canadian Music Centre’s Centrediscs label, as part of the “A Window on Somers” line, should be the opera Louis Riel (CMCDVD 16711) with music by Harry Somers and libretto by Mavor Moore and Jacques Languirand. While it would be a mistake to consider Louis Riel the first modern Canadian opera – a host of others come to mind including Willan’s Dierdre (1946), Beckwith’s Night Blooming Cereus (1953-58) and Somers’ own The Fool (1953, produced 1956) – it would be less so to acknowledge it as the most significant. Commissioned by the COC with funds from Floyd Chalmers (who also funded the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada and provided the CMC with its wonderful home at 20 St. Joseph St.) the opera was staged at O’Keefe Centre as part of Canada’s Centennial celebrations in 1967 with subsequent performances at Salle Wilfrid-Pelletier in Montreal. The COC revived Louis Riel in 1975 with performances in Toronto, Ottawa and, in its American debut, at the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. where it received rave reviews. Broadcast tapes of this Washington performance were later used to produce the first commercial release of the opera, a three LP set for Centrediscs in 1985.

It is fitting that the first DVD release by the Canadian Music Centre’s Centrediscs label, as part of the “A Window on Somers” line, should be the opera Louis Riel (CMCDVD 16711) with music by Harry Somers and libretto by Mavor Moore and Jacques Languirand. While it would be a mistake to consider Louis Riel the first modern Canadian opera – a host of others come to mind including Willan’s Dierdre (1946), Beckwith’s Night Blooming Cereus (1953-58) and Somers’ own The Fool (1953, produced 1956) – it would be less so to acknowledge it as the most significant. Commissioned by the COC with funds from Floyd Chalmers (who also funded the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada and provided the CMC with its wonderful home at 20 St. Joseph St.) the opera was staged at O’Keefe Centre as part of Canada’s Centennial celebrations in 1967 with subsequent performances at Salle Wilfrid-Pelletier in Montreal. The COC revived Louis Riel in 1975 with performances in Toronto, Ottawa and, in its American debut, at the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. where it received rave reviews. Broadcast tapes of this Washington performance were later used to produce the first commercial release of the opera, a three LP set for Centrediscs in 1985.

In 1969, which was incidentally the 100th anniversary of Riel’s original Red River Uprising, the opera was adapted for CBC television by producer Franz Kraemer and directed by Leon Major (who had also directed the stage performances). Although hard to tell from the Centrediscs packaging, it is this CBC production that is presented on the DVD, featuring most of the original cast, notably Bernard Turgeon who is brilliant throughout both vocally and as an actor in the title role. Patricia Rideout stands out as Riel’s mother; Mary Morrison is his sister and Roxolana Roslak his Cree wife (singing the now-familiar lullaby Kuyas). Joseph Rouleau is compelling as the dramatic and conflicted Bishop Taché, the Catholic priest who was charged with the role of intermediary between Riel and the government in Ottawa, with Cornelis Opthof, the originator of the deceitful John A. MacDonald role, replaced here by a suitably slimy Donald Rutherford.

Although the production values are somewhat dated (particularly the obvious use of “green screen” technology, presumably in its infancy) the production as a whole has withstood the passing of more than four decades admirably. The singers are in fine voice, many of them in their prime, and it is a joy to hear and see them at such close range. The music, which is a clever and compelling mixture of traditional melodies, lyrical arias – for the most part unaccompanied – and modern technique, including a very sparse but focussed orchestration with extensive use of percussion, is as convincing now as when it was first heard. The story, one of minority rights and duplicitous government action, not to mention a charismatic “visionary” leader who claims to hear/speak with the Voice of God is still a timely one, well told.

I do have a number of complaints however. The otherwise thorough booklet, which includes full plot synopsis, bilingual scene descriptions and libretto in four languages (English, French, Cree and church service Latin), makes no mention of the television production other than the CBC 1969 copyright notice. And while it is admirable that the opera is truly bilingual – i.e. the Métis often sing in French and the Anglos all in English – it is quite surprising to me that there are neither subtitles nor translations. The diction of the singers is surprisingly clear, so that those who do understand the languages can indeed understand the words, but what of those who might otherwise benefit from a bit of linguistic help? It is understandable that the opera stage of 1967 did not yet have the option of surtitles, but for the television production and, more to the point, the 2011 DVD release, surely it would have been a simple matter to add (optional) subtitles.

Other missed opportunities include the bonus features. We are given Mavor Moore’s introductions to parts one and two of the opera, but not as they would have appeared in 1969 as actual, and helpful, set-ups to the broadcast, but rather as afterwords. The other feature is a welcome discussion between Somers and Moore moderated by Warren Davis (who would go on to become the voice of new music in English Canada as host of CBC Radio’s Two New Hours). What we are not given is any present day commentary. Although the main creative forces are no longer with us – Harry Somers died in 1999 and Mavor Moore, although not noted in the biography provided, in 2006 – there are numerous luminaries (i.e. Bernard Turgeon, Joseph Rouleau and Mary Morrison) still alive and active. Surely these auspicious personalities could have shared some insights about this important Canadian achievement four decades on.

We know that “A Window on Somers” is basically a labour of love with a shoe-string budget - and kudos to Robert Cram for doing as much as he is able with it – but surely for a project of this magnitude with so much historical significance further funding could have been found to supplement the existing materials. That being said, we are thankful for the opportunity to revisit this glorious moment in Canada’s musical development and a time when our national broadcaster took pride in promoting and preserving our cultural heritage.

We welcome your feedback and invite submissions. CDs and comments should be sent to: The WholeNote, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4.

David Olds

DISCoveries Editor

discoveries@thewholenote.com