It all began as I was registering for an online service and was asked the security question “Who is your favourite author?” I realized that the answer has not changed in about 35 years since I first read William Gaddis’ The Recognitions (I hope this admission will not leave me vulnerable to identity theft!) which led to a re-reading of his final work, Agapē Agape. And there my story begins...

With Gaddis’ fixation on mechanical reproduction (specifically the invention of the player piano) and the ways technology changed the perception and availability of art in the 20th century, in particular the phenomenon of Glenn Gould and Gould’s wish to “eliminate the middleman and become [one with] the Steinway,” the stage was set for my wonderful summer’s journey.

It began with The Loser, Thomas Bernhard’s account of a fictional Glenn Gould’s studies in Salzburg with Vladimir Horowitz, and the devastating effects his presence (and his interpretation of the Goldberg Variations) had on two fellow students, the unnamed narrator and the character Wertheimer, who abandoned promising solo careers and were ultimately destroyed by the contact (Wertheimer in fact a suicide). Evidently Gaddis was reading Bernhard toward the end of his life and it was there he found the premise of Gould wanting to become the piano.

It was about this time that I realized that a book which had arrived at The WholeNote a few months earlier and which I had browsed but put down as being too dry and academic, The Musical Novel by Emily Petermann (Camden House 978-1-57113-592-6), might provide some insights and inspiration after all.

It was about this time that I realized that a book which had arrived at The WholeNote a few months earlier and which I had browsed but put down as being too dry and academic, The Musical Novel by Emily Petermann (Camden House 978-1-57113-592-6), might provide some insights and inspiration after all.

I still found it hard going – with its use of such unfamiliar words as inter-, intra- and multi-medial, poiesis and palimsestuous (as opposed to palimsestic, she explains), all of which I was able to make out from their roots and context but which I notice set off spell-check alarms – and ended up focussing on Chapter 5: “Structural Patterns in Novels Based on the Goldberg Variations.” Of the four books analyzed – Gabriel Josipovici’s Goldberg: Variations; Nancy Huston’s The Goldberg Variations; Rachel Cusk’s Bradshaw Variations and Richard Powers’ Gold Bug Variations – I had read (several times) all but the Cusk. The inclusion of this latter was in itself worth the effort of persevering with Petermann’s thesis.

I still found it hard going – with its use of such unfamiliar words as inter-, intra- and multi-medial, poiesis and palimsestuous (as opposed to palimsestic, she explains), all of which I was able to make out from their roots and context but which I notice set off spell-check alarms – and ended up focussing on Chapter 5: “Structural Patterns in Novels Based on the Goldberg Variations.” Of the four books analyzed – Gabriel Josipovici’s Goldberg: Variations; Nancy Huston’s The Goldberg Variations; Rachel Cusk’s Bradshaw Variations and Richard Powers’ Gold Bug Variations – I had read (several times) all but the Cusk. The inclusion of this latter was in itself worth the effort of persevering with Petermann’s thesis.

I took a break from the scholarly tome to (re)read each of the books in question. Reading them all together, interspersed with a number of recordings of the namesake, occupied me for most of a month and provided some delightful moments and revelations. Having now gone back to The Musical Novel to read Chapter 6 and the Conclusion has also furnished a number of explanations and clarifications, both about the novels in question and the structure of Bach’s masterpiece.

An example of the former is Cusk’s inclusion of a narrator-less chapter written entirely in dialogue without commentary (shades of Gaddis, although Cusk’s speakers are identified) which stuck in the craw of at least one reviewer as being non-sequiturial and annoying for its lack of context. Petermann points out that the chapter in question is parallel to Bach’s Variation XXVII in the structure of the book and is a literary representation of this “canon at the ninth,” which involves just two voices without the “commentary” of the bass line present in all of the other variations. So there is the context which the reviewer found lacking. Likewise Petermann explores the unique A-B structure of Variation XVI, the midpoint of Bach’s cycle, and relates it to several of the literary works, most notably the Josipovici. In an extension of the legend of the origin of another of Bach’s masterpieces, The Musical Offering, Josipovici recasts the story of Bach’s musical meeting with Frederick the Great to be Goldberg’s – a writer rather than a harpsichordist in this novel – literary joust with King George III and subsequent reworking of the King’s theme into “seven tiny tales” and a longer three-part cautionary story. Other insights abound…

Bach provided the title Clavierübung (keyboard study) consisting of an Aria with Diverse Variations for the Harpsichord with Two Manuals Composed for Music Lovers, to Refresh their Spirits. Johann Nikolaus Forkel, in the first biography of Bach written some six decades after the composer’s death, provided a background story from which the name we now associate with the work originated. Forkel tells us that Baron von Keiserling, an insomniac who employed a young harpsichord player named Goldberg to play him soothing and entertaining music at night from an adjoining room to help him sleep, or at least deal with his sleeplessness, commissioned Bach to write a set of suitable pieces for Goldberg to play. That story has long since been debunked, as listening to some of the more rambunctious variations might suggest, but the myth has continued to entice us for more than two centuries.

The recordings I revisited during this extensive immersion in the Goldberg Variations were of course Glenn Gould’s seminal 1955 and ultimate 1981 versions (in a 2002 three-CD commemorative package that includes an extended conversation between Gould and music critic Tim Page, SONY S3K 87703), plus Luc Beauséjour’s harpsichord rendition (Analekta fleur de lys FL 2 3132), Dmitri Sitkovetsky’s string trio arrangement with Sitkovetsky, Gérard Causé and Misha Maisky (Orfeo C 138 851 A, but you might choose a Canadian recording of the same arrangement with Jonathan Crow, Douglas McNabney and Matt Haimowitz on Oxingale OX2014, reviewed by Terry Robbins in the March 2009 WholeNote) and Bernard Labadie’s string orchestra version with Les Violons du Roy (Dorian xCD-90281), each of which brings very different aspects of the work to light and all of which I would recommend without hesitation. As I would the literary titles mentioned above.

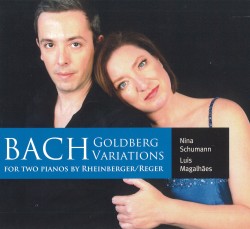

It was a new recording, Bach Goldberg Variations for Two Pianos, that drew my particular attention however. Evidently Joseph Rheinberger (1839-1901) felt that the original 1741 solo keyboard (two-manual harpsichord) work would provide enough material to keep two pianists busy and in 1883 made an arrangement for two pianos in which the liner notes tell us he “took substantial liberties with Bach’s original voicing, doubling melodies and fleshing out harmonies as he saw fit… [leaving] an unmistakably Romantic impression on the work.” Thirty years later Max Reger “smoothed out a few of the [remaining] rough edges” of Rheinberger’s adaptation and published the version recorded here in a wonderful performance by Nina Schumann and Luis Magalhães (TwoPianists Records TP1039213). It is this “Romantic” version for two pianos that comes the closest to being something I would like to hear at the edge of sleep. If I ever have the luxury of going to bed next to a room furnished with two grand pianos and such accomplished performers as Schumann and Magalhães I would love to put the Keiserling premise to the test.

It was a new recording, Bach Goldberg Variations for Two Pianos, that drew my particular attention however. Evidently Joseph Rheinberger (1839-1901) felt that the original 1741 solo keyboard (two-manual harpsichord) work would provide enough material to keep two pianists busy and in 1883 made an arrangement for two pianos in which the liner notes tell us he “took substantial liberties with Bach’s original voicing, doubling melodies and fleshing out harmonies as he saw fit… [leaving] an unmistakably Romantic impression on the work.” Thirty years later Max Reger “smoothed out a few of the [remaining] rough edges” of Rheinberger’s adaptation and published the version recorded here in a wonderful performance by Nina Schumann and Luis Magalhães (TwoPianists Records TP1039213). It is this “Romantic” version for two pianos that comes the closest to being something I would like to hear at the edge of sleep. If I ever have the luxury of going to bed next to a room furnished with two grand pianos and such accomplished performers as Schumann and Magalhães I would love to put the Keiserling premise to the test.

Having spent July immersed in Bach’s music, I spent August exploring the first half of Petermann’s treatise, devoted to the Jazz Novel, a genre with which I am mostly unfamiliar. As a matter of fact Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter is the only book covered that I had read, and Toni Morrison the only other author mentioned I had previously heard of. It turned out to be quite a challenge to track down many of the books discussed, but I am pleased to say that, after a mostly unfruitful search at the Toronto Public Library, with the aid of Toronto’s (few remaining) used book sellers and the Internet I have been able to find books by all of the authors discussed (including Xam Wilson Cartier, Christian Gailly, Jack Fuller, Stanley Crouch and Albert Murray). This too has been a very satisfying journey.

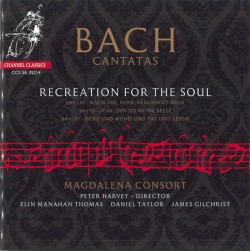

You might think that after all those Goldberg Variations I would have had enough of Bach for a while, but perhaps I am like those animals who, even when choices abound, continue eating a single food type until its source is depleted before moving on to something else (not that one could ever exhaust the available wealth of Bach recordings). For a change of pace I found that a new recording of Bach Cantatas entitled Recreation for the Soul featuring the Magdalena Consort (Channel Classics CCS SA 35214) did indeed provide a refreshing respite. I must confess that I am not well versed in Bach’s many cantatas – some 209 have survived – although I am of course familiar with some of the more famous arias. Listening to this new recording, which features stellar soloists Peter Harvey (bass and direction), Elin Manahan Thomas (soprano), Daniel Taylor (alto) and James Gilchrist (tenor) in one-voice-per-part arrangements, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the beloved melody I know as Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring appears not once but twice in the cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben (Heart and mouth and deed and life) BWV147, as the final chorale of Part One Wohl mir, dass ich Jesum habe (What joy for me that I have Jesus), and as the grand finale of the work, Jesus bleibet meine Freude (Jesus remains my joy). The other “musical offerings” on this marvelous disc are Jesu, der du Meine Seele (Jesu, by whom my soul) BWV78 and Nach dir, Herr, Verlanget Mich (Lord, I long for you) BWV150, both rich in Bach’s trademark melodies and counterpoint, heard here in a clarity not always found in full choral presentations. Highly recommended.

You might think that after all those Goldberg Variations I would have had enough of Bach for a while, but perhaps I am like those animals who, even when choices abound, continue eating a single food type until its source is depleted before moving on to something else (not that one could ever exhaust the available wealth of Bach recordings). For a change of pace I found that a new recording of Bach Cantatas entitled Recreation for the Soul featuring the Magdalena Consort (Channel Classics CCS SA 35214) did indeed provide a refreshing respite. I must confess that I am not well versed in Bach’s many cantatas – some 209 have survived – although I am of course familiar with some of the more famous arias. Listening to this new recording, which features stellar soloists Peter Harvey (bass and direction), Elin Manahan Thomas (soprano), Daniel Taylor (alto) and James Gilchrist (tenor) in one-voice-per-part arrangements, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the beloved melody I know as Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring appears not once but twice in the cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben (Heart and mouth and deed and life) BWV147, as the final chorale of Part One Wohl mir, dass ich Jesum habe (What joy for me that I have Jesus), and as the grand finale of the work, Jesus bleibet meine Freude (Jesus remains my joy). The other “musical offerings” on this marvelous disc are Jesu, der du Meine Seele (Jesu, by whom my soul) BWV78 and Nach dir, Herr, Verlanget Mich (Lord, I long for you) BWV150, both rich in Bach’s trademark melodies and counterpoint, heard here in a clarity not always found in full choral presentations. Highly recommended.

Hoping to wean myself gently off the Bach overdose and realizing that no one writing for solo cello would be able to avoid at least some influence of the master, I decided to check out Lady in the East, Solo Cello Suites 1-3 by BC composer Stephen Brown, featuring Hannah Addario-Berry (stephenbrown.ca). The opening notes of Takakkaw Falls, Suite No.1 confirmed my suspicion regarding echoes of Bach, but almost immediately the contemplative Air established its own independent voice and the following Strathspay & Reel and Slow Waltz, although based on dance patterns like a Baroque suite, were obviously drawing inspiration from different cultural sources – Canadian folk songs and fiddle tunes. It is not until halfway through the final Jig that we once again find a nod to Bach in a stately middle passage before a return to the playful fiddle tune of the opening.

Hoping to wean myself gently off the Bach overdose and realizing that no one writing for solo cello would be able to avoid at least some influence of the master, I decided to check out Lady in the East, Solo Cello Suites 1-3 by BC composer Stephen Brown, featuring Hannah Addario-Berry (stephenbrown.ca). The opening notes of Takakkaw Falls, Suite No.1 confirmed my suspicion regarding echoes of Bach, but almost immediately the contemplative Air established its own independent voice and the following Strathspay & Reel and Slow Waltz, although based on dance patterns like a Baroque suite, were obviously drawing inspiration from different cultural sources – Canadian folk songs and fiddle tunes. It is not until halfway through the final Jig that we once again find a nod to Bach in a stately middle passage before a return to the playful fiddle tune of the opening.

I find it interesting to note that the suite was originally composed for solo flute. In my correspondence with Hans de Groot about the disc of Francis Colpron’s transcriptions for recorder reviewed elsewhere in these pages I mentioned that one of my favourite versions of the Bach cello suites was Marion Verbruggen’s performance on the recorder. I’m pleased to note that the process of translation can also work the other way around, from flute to cello.

The disc includes two other suites (evidently Brown has composed six in all, so far), Fire, which is influenced by the classic rock of Hendrix, Procol Harum, Cream and the like, adapted very effectively and idiomatically for solo cello, with a contrasting slow Recitative and Aria movement again reminiscent of Bach, and There Was a Lady in the East in which Brown returns to folk songs and fiddle tunes. As an amateur cellist I am pleased to note that the sheet music for these works is available from the Canadian Music Centre (musiccentre.ca). I availed myself of the CMC’s purchase-and-print-it-yourself service and have enjoyed the challenge of working on the first suite in the past few weeks.

My final selection this month does not show any noticeable influence of J.S. Bach, but does feature solo cello with German-Japanese Danjulo Ishizaka accompanied by pianist Shai Wosner. Grieg, Janáček, Kodály (Onyx 4120) features three relativelyobscure, or at least rarely recorded, works for cello and piano – Janáček’s dark and lyrical Pohádka (Fairy Tale) and his brief, dramatic Presto, whose origin is unclear but which may have been meant originally as a movement of the fairy tale suite, and Grieg’s Cello Sonata in A minor, Op.36. Ishizaka’s committed performance of the Grieg and Janáček works makes me wonder why they aren’t more often played. After all, these are mature works by respected composers who did not publish much in the way of chamber music – in the case of Grieg two violin sonatas and a string quartet and Janáček just a smattering of works for violin and piano, two string quartets and a woodwind sextet. That alone would make this recording important, but for me it is the centrepiece of the disc, a staple of the modern repertoire, Kodály’s Solo Cello Sonata Op.8 which is most worthy of note.

My final selection this month does not show any noticeable influence of J.S. Bach, but does feature solo cello with German-Japanese Danjulo Ishizaka accompanied by pianist Shai Wosner. Grieg, Janáček, Kodály (Onyx 4120) features three relativelyobscure, or at least rarely recorded, works for cello and piano – Janáček’s dark and lyrical Pohádka (Fairy Tale) and his brief, dramatic Presto, whose origin is unclear but which may have been meant originally as a movement of the fairy tale suite, and Grieg’s Cello Sonata in A minor, Op.36. Ishizaka’s committed performance of the Grieg and Janáček works makes me wonder why they aren’t more often played. After all, these are mature works by respected composers who did not publish much in the way of chamber music – in the case of Grieg two violin sonatas and a string quartet and Janáček just a smattering of works for violin and piano, two string quartets and a woodwind sextet. That alone would make this recording important, but for me it is the centrepiece of the disc, a staple of the modern repertoire, Kodály’s Solo Cello Sonata Op.8 which is most worthy of note.

Presented in a context of “folkloric” works in the liner essay by Ishizaka, I find it hard to make that connection. Of course Kodály worked with Bartók in the early years of the 20th century collecting and transcribing literally thousands of folk songs from Hungary and surrounding lands, and this experience had a lasting influence on both composers and their music. But frankly I don’t hear it here. From the abrasive opening through a contemplative middle movement and on to its driving finale, this extended work from 1915 is a thoroughly modern, uncompromising tour de force which extends the cello’s sonic possibilities with its re-tuned and simultaneously plucked and bowed strings. Ishizaka’s performance brings out all this and more. It’s a welcome addition to the discography.

I mentioned above that I imagined that all composers writing for solo cello would be influenced by Bach’s solo suites. I find myself unable to find these influences in Kodály however, although I have come up with an explanation. It was Pablo Casals who first brought widespread attention to the Bach suites, having stumbled upon the score in 1890 at the age of 13. He then proceeded to spend several decades working on the suites and developing them as the performance showpieces we know today. Before that time it seems they were regarded as mere finger exercises, learning pieces not fit for the concert hall. Although Casals did record four of the six movements of the C Major Suite in 1915, the year Kodály composed his Sonata, it would be two more decades before he made his seminal recordings of the entire cycle. I think it may well be that Kodály was not aware of the Bach Suites when he composed his masterwork. If this is indeed the case, it is an even more remarkable achievement.

We welcome your feedback and invite submissions. CDs and comments should be sent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., The Centre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4.

David Olds, DISCoveries Editor

discoveries@thewholenote.com

The Karajan Symphony Edition (4778005) is an extraordinary offering: 38 CDs for no more than $60 retail! Here are the complete Beethoven symphonies (1972 version) + overtures; the four Brahms symphonies + Haydn Variations and Tragic Overture, the nine Bruckner symphonies, Haydn’s Paris and London Symphonies; Mendelssohn’s five symphonies; Mozart’s late symphonies; Schumann’s four symphonies and Tchaikovsky’s six symphonies, etc. All the discs reflect the latest remasterings. How is this giveaway price possible? There are a few factors to consider: DG owns the masters; the recording sessions are long ago paid for and DG is making a lot of copies for worldwide distribution. It still is hard to figure out, but who’s complaining?

The Karajan Symphony Edition (4778005) is an extraordinary offering: 38 CDs for no more than $60 retail! Here are the complete Beethoven symphonies (1972 version) + overtures; the four Brahms symphonies + Haydn Variations and Tragic Overture, the nine Bruckner symphonies, Haydn’s Paris and London Symphonies; Mendelssohn’s five symphonies; Mozart’s late symphonies; Schumann’s four symphonies and Tchaikovsky’s six symphonies, etc. All the discs reflect the latest remasterings. How is this giveaway price possible? There are a few factors to consider: DG owns the masters; the recording sessions are long ago paid for and DG is making a lot of copies for worldwide distribution. It still is hard to figure out, but who’s complaining? Beethoven The Symphonies – Karajan’s 1963 performances are widely considered to be not only the onductor’s best but the best. DG has completely re-mastered the analogue tapes at 24 bit/96 kHz and has also produced a “Pure Audio Blu-ray disc” of the nine plus a rehearsal of the Ninth that is included in a limited edition, smartly bound as a hard cover book (94793442, 6 discs). Karajan was a longtime admirer of Toscanini and preparing for this important cycle, he studied Toscanini’s recordings. Both conductors’ cycles remain in print.

Beethoven The Symphonies – Karajan’s 1963 performances are widely considered to be not only the onductor’s best but the best. DG has completely re-mastered the analogue tapes at 24 bit/96 kHz and has also produced a “Pure Audio Blu-ray disc” of the nine plus a rehearsal of the Ninth that is included in a limited edition, smartly bound as a hard cover book (94793442, 6 discs). Karajan was a longtime admirer of Toscanini and preparing for this important cycle, he studied Toscanini’s recordings. Both conductors’ cycles remain in print. On December 18, 1962 defying admonitions from Premier Khrushchev and the Soviet Presidium, the first performance of Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony was given in Moscow and dutifully ignored by the press. The composer had set five of Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poems, including the recently published Babi Yar, the subject of which was anti-Semitism and the well documented, wholesale massacre of Jews in Kiev by the Nazis in WWII. Further performances were banned until Yevtushenko altered the text, which he did, but not before December 20 when there was a repeat performance with the original text. Praga has issued a hybrid SACD of that event with Kirill Kondrashin conducting the Moscow Philharmonic, two choirs and Vitaly Gromadsky, tenor and speaker (PRD/DSD 350089, texts and translations included). This is the same performance heard on the complete 12CD Russian set (CDVE04241) but now delivered in a more impressive, open and persuasive sound. More than a performance, this is a declamation. I know of no other recorded performance to come even remotely close to the intensity and impact of this significant and valuable document.

On December 18, 1962 defying admonitions from Premier Khrushchev and the Soviet Presidium, the first performance of Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony was given in Moscow and dutifully ignored by the press. The composer had set five of Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poems, including the recently published Babi Yar, the subject of which was anti-Semitism and the well documented, wholesale massacre of Jews in Kiev by the Nazis in WWII. Further performances were banned until Yevtushenko altered the text, which he did, but not before December 20 when there was a repeat performance with the original text. Praga has issued a hybrid SACD of that event with Kirill Kondrashin conducting the Moscow Philharmonic, two choirs and Vitaly Gromadsky, tenor and speaker (PRD/DSD 350089, texts and translations included). This is the same performance heard on the complete 12CD Russian set (CDVE04241) but now delivered in a more impressive, open and persuasive sound. More than a performance, this is a declamation. I know of no other recorded performance to come even remotely close to the intensity and impact of this significant and valuable document. His Decca Ring Cycle was years away in October of 1961 when Georg Solti conducted a new Die Walküre at Covent Garden. As I recall, it was Hans Knappertsbusch that Decca originally had in mind for their project. Testament brings us that live performance of October 2nd as recorded by the BBC in appropriately dynamic mono sound (SBT4-1495, 4 CDs). Upon the persuasive urging of Bruno Walter, Solti had just accepted the post of music director of the Covent Garden Opera Company and this performance presages the discipline and vitality of productions to follow, as his many recordings attest. Hearing the voice of the not quite 35-year-old Jon Vickers as the unfortunate Siegmund in the first act and into the second is still, to this day, an electrifying experience. Claire Watson turns in a believable Sieglinde, the only character to appear in all three acts. Brünnhilde is the Finnish Wagnerian soprano Anita Välkki and Wotan is Hans Hotter, in whom I was slightly disappointed in the final scene where he initially seems to be pushing his voice. Perhaps he needed a broader tempo but as the opera runs its course he is back on top. The whole production is very satisfying with splendid orchestral sound and no off-mike voices.

His Decca Ring Cycle was years away in October of 1961 when Georg Solti conducted a new Die Walküre at Covent Garden. As I recall, it was Hans Knappertsbusch that Decca originally had in mind for their project. Testament brings us that live performance of October 2nd as recorded by the BBC in appropriately dynamic mono sound (SBT4-1495, 4 CDs). Upon the persuasive urging of Bruno Walter, Solti had just accepted the post of music director of the Covent Garden Opera Company and this performance presages the discipline and vitality of productions to follow, as his many recordings attest. Hearing the voice of the not quite 35-year-old Jon Vickers as the unfortunate Siegmund in the first act and into the second is still, to this day, an electrifying experience. Claire Watson turns in a believable Sieglinde, the only character to appear in all three acts. Brünnhilde is the Finnish Wagnerian soprano Anita Välkki and Wotan is Hans Hotter, in whom I was slightly disappointed in the final scene where he initially seems to be pushing his voice. Perhaps he needed a broader tempo but as the opera runs its course he is back on top. The whole production is very satisfying with splendid orchestral sound and no off-mike voices. The late Claudio Abbado enjoyed a career that spanned more than 50 years, during which he conducted the world’s finest orchestras. His last recorded concerts, those of August 16 and 17, 2013 were with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra. Accentus has issued a splendid DVD of the complete program of that opening concert of the season, comprising Brahms’ Tragic Overture, Schoenberg’s Song of the Wood Dove from Gurrelieder and Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony (ACC20282). I doubt that there could ever be a nobler and more flowing version of the Tragic Overture than heard here. Gurrelieder, Schoenberg’s great ultra-Romantic post-Wagnerian masterpiece has been a special favourite of mine since I first heard the Stokowski/Philadelphia recording. For me it is a heady experience. The Song of the Wood Dove that brings the news of the death of Tove to King Waldemar stands well on its own, magnificently conveying the enormity of the awful news. The immense augmented orchestra supports the outstanding mezzo-soprano Mihoko Fujimura as the Wood Dove. The very fine Eroica is played with total commitment, immaculate in detail and dynamics and enormous authority. A well balanced, albeit unusual program played with effortless virtuosity and a fine showcase for the late conductor.

The late Claudio Abbado enjoyed a career that spanned more than 50 years, during which he conducted the world’s finest orchestras. His last recorded concerts, those of August 16 and 17, 2013 were with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra. Accentus has issued a splendid DVD of the complete program of that opening concert of the season, comprising Brahms’ Tragic Overture, Schoenberg’s Song of the Wood Dove from Gurrelieder and Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony (ACC20282). I doubt that there could ever be a nobler and more flowing version of the Tragic Overture than heard here. Gurrelieder, Schoenberg’s great ultra-Romantic post-Wagnerian masterpiece has been a special favourite of mine since I first heard the Stokowski/Philadelphia recording. For me it is a heady experience. The Song of the Wood Dove that brings the news of the death of Tove to King Waldemar stands well on its own, magnificently conveying the enormity of the awful news. The immense augmented orchestra supports the outstanding mezzo-soprano Mihoko Fujimura as the Wood Dove. The very fine Eroica is played with total commitment, immaculate in detail and dynamics and enormous authority. A well balanced, albeit unusual program played with effortless virtuosity and a fine showcase for the late conductor.