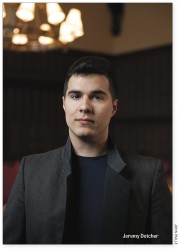

“My Own Stamp” – Jeremy Dutcher in Conversation

For someone who’s only been working full-time as a musician for less than a year, Jeremy Dutcher has been keeping busy.

For someone who’s only been working full-time as a musician for less than a year, Jeremy Dutcher has been keeping busy.

Fresh off the heels of an artist residency at the National Music Centre in Calgary and a solo appearance in Soundstreams’ Electric Messiah, Dutcher’s 2017 calendar is already starting to fill – appearing with the Toronto Consort on February 3 and 4, in Winnipeg and Kingston in March, and at the Music Gallery in April – and beyond that he has a clear artistic vision in mind. A classically trained operatic tenor and composer and a member of Wolastoq (Maliseet) First Nation, his performance practice blends his classical background with his interest in jazz and the contemporary, plus traditional music from his community. Here in Toronto, the New Brunswick-born singer is making waves with his distinct compositional voice – using song as his platform for Indigenous cultural reclamation and rediscovery.

A lot of these upcoming gigs will include performances from his album-in-progress – Dutcher’s first. Titled Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonaw, the album will present Dutcher’s own arrangements of traditional Wolastoqiyik songs, and is slated for release at the end of 2017.

In many cases, the songs on this album haven’t been heard in Dutcher’s community for decades. “On the East Coast, we’ve been dealing with the longest period of colonization – of cultural friction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people,” he explained when I sat down with him last week. “We’ve lost a lot...Growing up, much of what was thought of as ‘traditional’ music wasn’t actually sung in the language or even originating in our territory. For me, I wanted to think about songs that are specific to my nation.”

Finding those songs required legwork. Dutcher visited the archives of the Museum of Canadian History in Gatineau, Quebec, where he transcribed wax cylinder recordings made in Wolastoq territory by ethnographer William H. Mechling in the early 1900s – one of the earliest field recordings of Wolastoqiyik music.

“Listening to these recordings for the first time, I felt a profound connection with these voices,” says Dutcher. “The sound quality may be scratchy and unclear, but [they] provide a unique glimpse into the musical lives of my ancestors.” He’s also being careful to recognize the bias of the original ethnographer – and take the work of musical reclamation for his community seriously. “For me, as someone who’s re-interpreting [these recordings], I wanted to question – as an artist and as somebody who wants to put my own stamp on this – how do I stay true to the melodies and give them the life that they deserve, without taking on some of the bias that’s really built into the recordings?” he says. “And I want to do it really right – you only get one first go.”

Dutcher assures that the arrangements on the album, which will be for voice, piano, string quartet and some percussive elements, will be similar to his own work as an artist – classically influenced, but broad-ranging. “[Classical music] does inform the way that I sing, and the way that I play. But for me, this project is also so much more than that,” he explains. “It’s [also] complex, because Indigenous communities are not just one community,” he continues. “When you think about Indigenous music, a lot of people go straight to big drum songs. So I think a big part of this project is also education: to blow up people’s ideas about what Indigenous music is, and what it’s going to be.”

The songs on the album will also all be recorded in their original language – and for Dutcher, that part is non-negotiable. “It’s all in Maliseet, and I don’t apologize for that,” he says. “I do sometimes translate, but sometimes not…and that’s a pretty strong statement, especially in this day and age. In my community there are only about 500 people who speak the language left. It’s at that place where if people in my generation aren’t taking linguistic reclamation, and the work that entails, seriously, then we’re going to lose our language, and [we’re going to lose] that entire way of seeing the world.

“Going forward, I can imagine writing stuff in English,” he adds. “But for this one, I really wanted to say, this is who I am. This is the language that I choose to sing in. Come along for the ride.”

The album is a timely one. It’s certainly not lost on Dutcher that a number of the upcoming shows he’s been asked to appear at fit under the year’s growing banner of sesquicentennial concerts, for the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation – and that, even when well-meaning, when it comes to Indigenous representation it can be easy for non-Indigenous music presenters to miss the mark.

“As an Indigenous artist, I’m thinking a lot about the sesquicentennial,” he says. “What is it that we’re celebrating? 150 years of what? Of ‘nationhood,’ which at its fundament is negating nationhood that has existed in this place for much longer than 150 years.

“[This year], people really want to highlight an Indigenous voice as part of the [national] fabric. But for me, it has to have a critical lens. If it doesn’t then I’m not at all interested.”

I mention the trepidation that I’ve felt from a number of local arts workers – myself included – about arts organizations that seem too eager to jump unquestioningly onto the sesquicentennial bandwagon. I’ve found myself increasingly skeptical of all shows painted with the “Canada 150” brush – even those that appear to be doing good work. It’s a sentiment that Dutcher shares.

“I think that as both audience members and as practitioners, it’s okay to say, ‘I’m very skeptical about this – about all of this’,” he says. “And within that musical space, to question the hegemony of the Western canon and how art music is framed, and which voices get privileged within that framework. It’s an important question to ask and to keep asking. All the time, but especially in a year like this.”

The first of Dutcher’s upcoming gigs, the Toronto Consort’s “Kanatha/Canada” program on February 3 and 4, seems to be doing some of that good work. Looking at the first meeting between French settlers and Indigenous members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, the show will be presenting the Consort in a performance of John Beckwith’s work Wendake/Huronia, as well as French-Canadian folk songs brought over with the early colonists. The members of the Consort will be joined onstage by Dutcher, First Nations singers Marilyn George and Shirley Hay, and Wendat Traditional Knowledge Keeper Georges Sioui, who collaborated with Beckwith on the composition of his piece when it was premiered in 2015. A big part of the concert, in a diversion from the Consort’s usual musical focus as early-music performers, will be to provoke discussion about new musical dialogue between European (Eurocentric) and Indigenous communities.

Dutcher will be speaking onstage and sharing some of the pieces from his forthcoming album, using the material that he found in the archives to bring forth a current-day, Indigenous perspective. For Dutcher, it’s an opportunity to bring his own musical work into a wider discussion, with new audiences. “When [David Fallis, of the Toronto Consort] brought me this project,” he says, “we had long conversations about the implications and about how to take this on in a good way. I’m hopeful that those conversations will continue even on the nights of the show.

“For me,” he continues, “it’s about reaching audiences that I otherwise couldn’t with what I do. My work speaks to certain audiences, but the Toronto Consort has their own set of people who attend their concerts and admire what they do. Those people might not have an entry point into conversations about Indigenous issues, or about Indigenous identity within the framework of a sesquicentennial. So for me, it’s about creating dialogue – and that’s what I hope it will do.”

Following shows in Winnipeg and Kingston – the former a premiere of his new choral composition, and the latter a program of songs featuring Dutcher, mezzo-soprano Marion Newman and multidisciplinary artist Cheryl L’Hirondelle at the city’s new Isabel Bader Centre on March 28 – Dutcher will return to Toronto to host another discussion, this time at the Music Gallery.

Co-produced by the Music Gallery and RPM.fm, the April 25 event is a panel titled “What Sovereignty Sounds Like: Towards a New Music in Indigenous Tkaronto.” The discussion will centre around contemporary Indigenous music in the local scene, and how settlers can best respect and support local spaces for Indigenous and transnational musical performance. Dutcher will host and moderate, and will be joined by Anishinaabe electronic musician Ziibiwan.

“David Dacks [the Music Gallery’s artistic director] has been in conversation about these things for as long as I’ve known him,” says Dutcher. “In the past year and a half, I’ve known him to reach out and offer space – one of the big things that as Indigenous artists we lack access to.

“I went to a gathering in Vancouver this year, where Indigenous scholars and Indigenous artists were able to join in conversation together,” Dutcher adds. “I realized there how little that actually happens: how infrequently we’re not just a token in a room, and how infrequently we’re able to sit down and have those dialogues between our practitioners and theorists. I think that gatherings like that are a good model for creating those spaces where Indigenous perspectives are centred, and where we’re not having to argue and fight and educate every time we walk into a room...because that’s often how it goes.”

With an increasing awareness of Indigenous issues among non-Indigenous Canadians, it seems as though requests – both explicit and implied – for local Indigenous voices to speak for their communities and educate others are also inevitably on the rise. And while on the one hand Dutcher encourages the learning process, he also is articulate about the clear problems with this: first, that it is the responsibility of settlers to educate themselves instead of demanding lessons from their Indigenous peers; and second, that asking any single person – Indigenous or otherwise – to bear the responsibility of representing their entire community in the public eye is a big, and ignorant, ask.

“I don’t begrudge people for it, because that’s a systematic thing,” he says. “That’s a lack of education, a lack of having relations with the first people in this land. It’s built into society…But it is exhausting to be an educator all the time. There are so many things that artists who are not in our community don’t even have to consider.

“As a young person and someone who grew up mostly off-reserve, I struggle to speak to the breadth of things that our community has to say,” Dutcher continues. “I just try to centre [my work] on my own experience, and how I experience moving through different musical and political worlds.”

Focusing on his music – and on what that means for his community – has been a learning curve for him, too. The album, and the other musical work that has come along with it, has proven an all-encompassing, but ultimately rewarding, task.

“I can’t deny who I am as a person, and my positionality within this landscape of reclamation,” says Dutcher. “I’m a young Indigenous person, but I’m also a city dweller, I’m half-white, I’ve spoken English my whole life, I studied classical music…there are all of these things that have made me a bit of an outsider. But I’ve come to find beauty and strength in that. That’s one thing that this project has taught me.”

What all of these projects seem to have in common is how they reveal the layers of complexity that musical identity can have – both in the physical space of this continent and within the rapidly expanding world of what we label as classical music. And what Dutcher’s own hard work shows is that, now more than ever, it is not the time to be complacent about the problematic ways that we as classical musicians represent our craft. Instead, as he suggests, it’s an apt moment to criticize, to complicate and to build a vocabulary for understanding the future of transcultural performance. Dutcher is one of the artists out there who is making musically powerful, relevant work, and who has the chops and conscientiousness to do it well. It’s a good time to listen.

Sara Constant is a Toronto-based flutist and musicologist, and is digital media editor at The WholeNote. She can be contacted at editorial@thewholenote.com.